INTRODUCTION

There is no doubt that one of the greatest additions to the dentist’s diagnostic and treatment planning toolbox in recent years has been CBCT imaging. This is a radiographic imaging modality that has opened up a whole new field of view (no pun intended) when it comes to visualizing dental patients’ anatomy and pathology. It has almost eliminated the guesswork in trying to determine the morphology and position of structures, such as the relationship of impacted teeth to their surrounding structures, as well as the determination of the presence, etiology, and behavior of infections and other jaw pathologies. This is most evident when examining a tooth for infection that lies in planes that are not easily examined in 2D imaging, such as the buccal, lingual, and furcation aspects of the teeth, enabling an accurate diagnosis for a patient with occult dental infection. This ability to correctly diagnose the patient’s condition enables the dentist to treat him or her appropriately.

But with this incredible improvement in diagnostic capability comes great responsibility to our patients, which is to become proficient in the examination and interpretation of CBCT scans. The interpretation of radiographic imaging is considered a dental procedure, and just like all dental procedures, an immense amount of learning needs to occur to make the examiner effective and efficient in this procedure. The time and commitment to reach this proficiency may vary from one practitioner to the next, but the fact remains that unless you have been formally trained in the review of CBCT, it is not a skill that comes intuitively. Building the vocabulary and methodology can be overwhelming if no formal training in this field has been undertaken. Radiographic diagnosis is an important link in the diagnostic chain.

As an oral and maxillofacial radiologist, I have witnessed an amazing change in our ability to observe and diagnose our patients’ conditions. These changes are a paradigm shift from how most of us were taught radiology in dental school. The interest in using this modality has multiplied tremendously. Still, not every dentist who uses CBCT in his or her office has the proper training to review the scans as many dental schools have still not incorporated 3D CBCT in their dental education curricula. One of my professional goals is to fill this educational gap and help dentists learn how to diagnose their patients’ conditions on CBCT scans. Throughout the years, I’ve compiled some fundamental pointers that can help shift your thinking and start you on the path of 3D analysis.

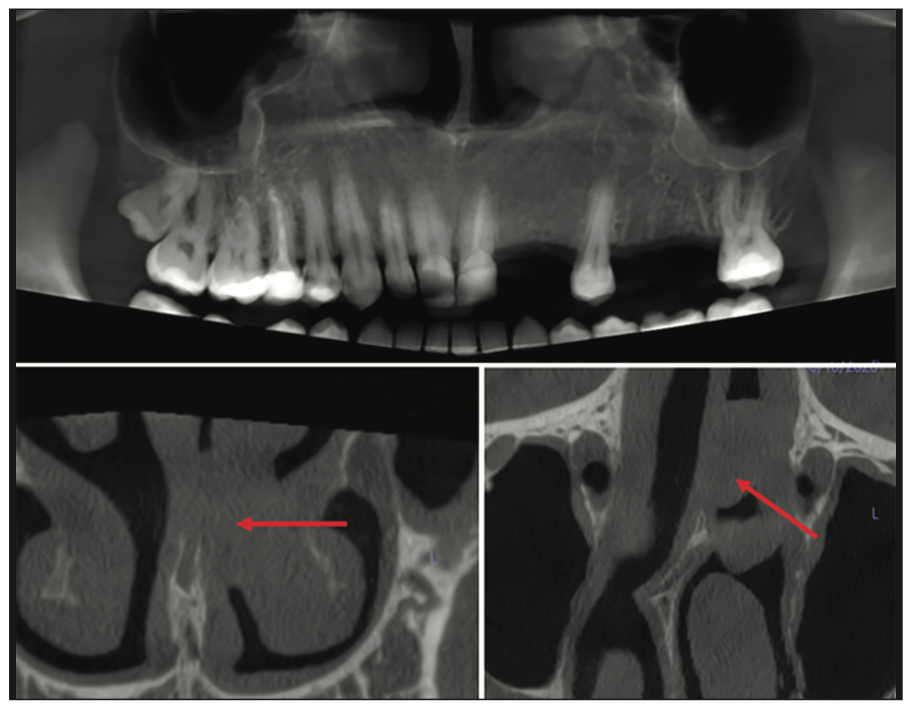

1. Lose the tunnel vision. This is probably the most important trait that you have to learn. All human beings have biases and preferences. When it comes to dentists, we like to look at the things we are comfortable with and tend to have a fine-tuned aesthetic eye. When it comes to radiographic imaging evaluation, our eyes tend to drift to the area of interest we are treating, and teeth always grab our attention. The problem with doing that is that it satisfies our curiosity, and we are not driven to look further, thus increasing the likelihood of “missing something” (Figure 1). The advice that I give dentists I am training is to consciously and purposefully avoid looking at the area of interest, namely, the teeth, and follow a systematic review process of the images that are repeatable and replicable on every single patient scan. Once you are done with all other structures, then analyze teeth systematically.

Figure 1. A dentist acquired and analyzed this scan for implant placement. The dentist missed the lesion in the nose. Establishing an evaluation method that eliminates tunnel vision is imperative to avoid missing non-dentoalveolar pathology.

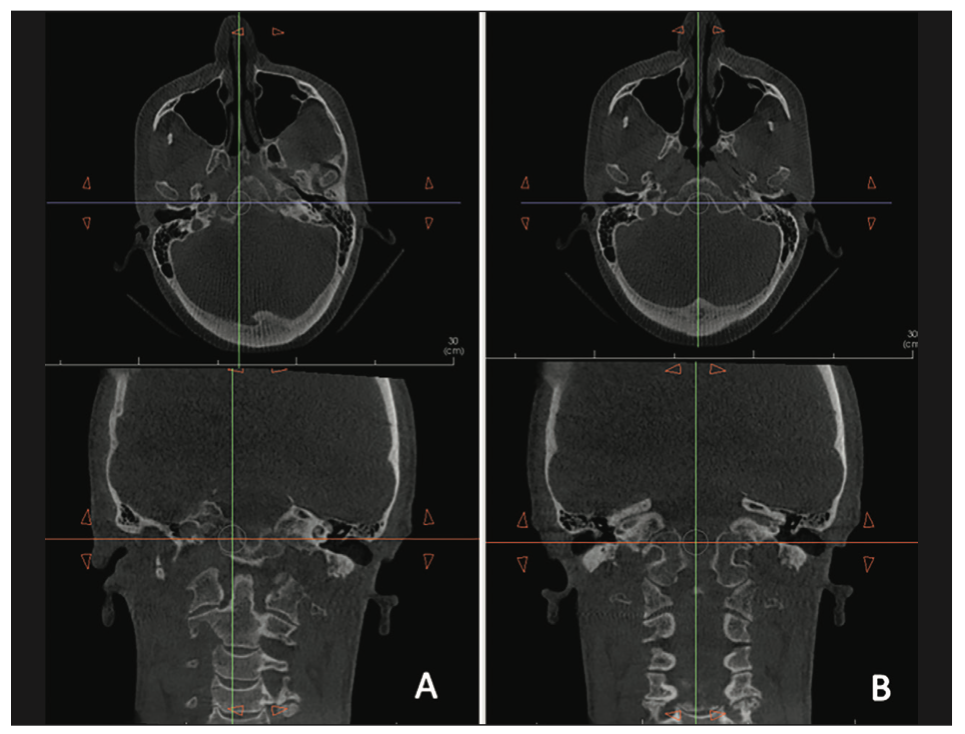

2. Reorient the scan. This step is crucial as it aligns the complex structures of the head with the anatomical planes and allows for a more symmetric analysis. This is important as the multitude of anatomic structures and conditions that occur in the head and neck can be confusing and difficult to visualize if the right and left sides of the head are not at the same level. Most scans will be acquired with the patient’s head off-center, depending on how they were seated in the CBCT unit. This reorientation corrects for these tilts and allows for a more systematic and symmetrical analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 2. (a) Unoriented CBCT scan. (b) Scan reoriented to the external auditory canals to allow for a more symmetric evaluation.

3. Recognize that CBCT interpretation requires “2 brains.” While not quite anatomically accurate, the reality is that, because of the complexity of the task at hand, it is best to approach it in 2 steps: (1) thinking like a radiologist and (2) thinking like a dentist. The radiologist’s part of the brain starts the process by analyzing the structures of the craniofacial complex for abnormalities. This requires an intimate knowledge of head and neck anatomy as well as disease processes in the craniofacial complex. The process is facilitated by the reorientation of the scan (see above) and the adaptation of a systematic method of review. When the review of all the head and neck structures on this scan is complete, the dentist part of the brain can kick in, looking at the teeth systematically as we count from the upper right quadrant and then across and around to the lower right quadrant. Once the search for dental abnormality is complete, we can move on to the primary indication of the scan (implant analysis, dental impaction, boundary conditions in orthodontics, TMJ, airway, etc).

4. Develop a systematic method and stick to it. The method you learn will depend on your teacher. Due to the complexity of the task, it is best to learn from an oral and maxillofacial radiologist. These professionals have dedicated their lives to understanding this anatomy and the conditions that may arise in this area of the human body. They are also familiar with the dental procedures you are performing and can guide you on how best to optimize the visualization of the anatomy to fit your procedure. In general, when visualizing the anatomy, it helps to look at one structure at a time, compare both sides, and do that systematically from the top of the scan to the bottom. Needless to say, knowledge of anatomy is key to accurate and successful analysis.

5. Learn your anatomy. This is half of the game. If you know the lay of the land, you will easily pick up a variation in that landscape. This is a daunting task, especially if your last encounter with anatomy was in dental school, but this task should be taken in small bites over time. Some resources that have helped me tremendously are cadaver courses, Netter’s Head and Neck Anatomy for Dentistry, and investing time learning radiographic anatomy from books and online resources.

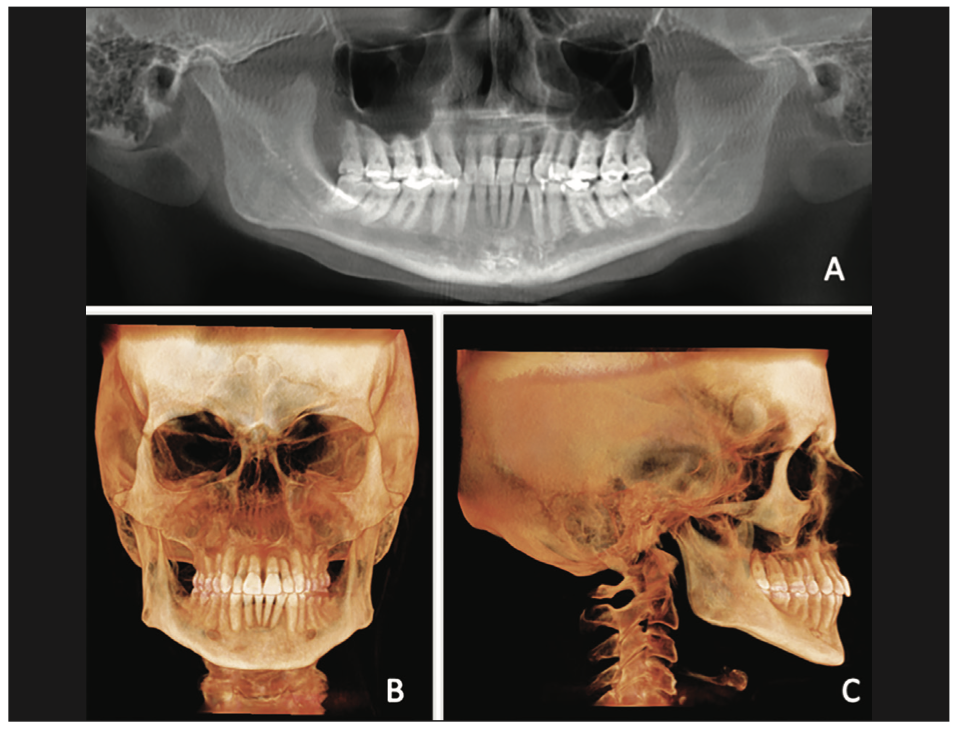

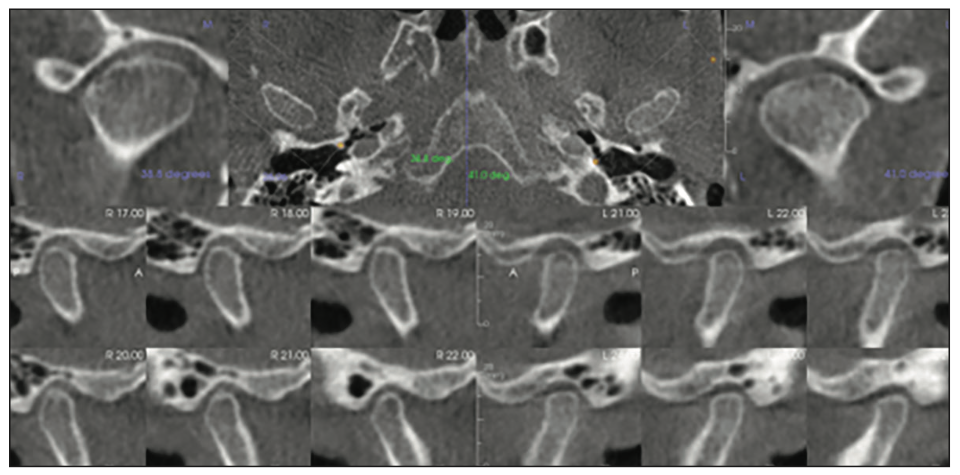

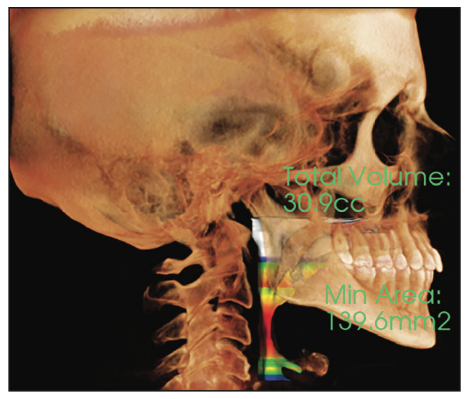

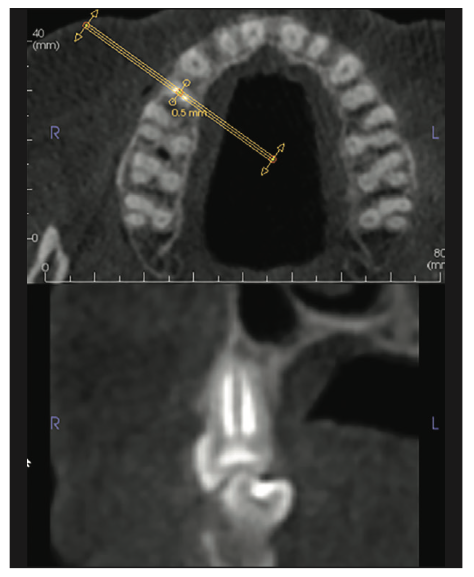

6. Know how to use your CBCT reading software. The CBCT volume has a great deal of information on it. This information may not be readily displayed on the scan as it presents. Understanding the bells and whistles that come with your software enables you to extract this information by creating the views, cross sections, and reformations necessary to cinch the diagnosis (Figures 3 to 6).

Figure 3. Diagnostic CBCT reformations that can be used to evaluate the patient’s overall jaw condition and skeletal morphology. (a) A panoramic reformation can be used to assess the overall dentoalveolar condition and jaw anatomy. Three-dimensional reforma- tions in the (b) frontal and (c) lateral views are static representations of a movable 3D model of the skull that can be evaluated in any plane.

Figure 4. TMJ cross sections in the corrected sagittal, coronal, and axial planes can be used to demonstrate the TMJ condition and the spatial relationships of the TMJ osseous components.

Figure 5. A 3D volumetric reformation of the oropharyngeal airway can be created from CBCT data.

Figure 6. Custom cross sections can be used to assess teeth and other structures in any plane for the presence of abnormality.

CONCLUSION

Of course, there is much more to learn. These points are meant to at least start you on the path of thinking required for the CBCT evaluation and interpretation procedure. It is a magnificent new world of diagnosis for you and your patients, and I hope you will enjoy your learning journey!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Tamimi runs her home-based oral radiology private practice in Orlando. She has authored multiple textbooks and book chapters and offers multiple courses and private instruction on how to read CBCT and MRI scans. She lectures worldwide on these topics. Her online courses can be found on beamreaders.com/courses. She can be reached at info@inspire-imaging.com.

Disclosure: Dr. Tamimi reports no disclosures.