INTRODUCTION

In Parts 1 and 2 of this 4-part series, the concept of “Upgradeable Dentistry,” a subject of particular importance given the current economic conditions, was discussed. This concept, as previously defined, is the diagnostic and treatment paradigm that allows patients to achieve ideal dentistry in phases according to their emotional and financial situation.1

|

|

||

|

The concept of “upgradeability” is consistent with the statement that dentistry is dynamic process, not a static event. Too often in dentistry, the insurance companies’ fee schedules become synonymous with treatment recommendations. If we educate our patients that dentures are not a destination, but a stop along the path to reclaiming proper aesthetics, phonetics, and function, people will be more receptive to a continual dental journey. By introducing the concepts of bone grafting, sinus augmentation, ridge spreading, etc, patients will begin to take responsibility for the continual bone loss caused by edentulism worsened by ill-fitting denture wear.2

REMOVABLE PROSTHESES

A removable prosthesis (or RP-5 prosthesis, using nomenclature defined by Dr. Carl Misch) is a prosthesis that is removable and has implant and soft-tissue support. This prosthesis can sit on a combination of implants which are independent, or joined with a bar.3 The use of bars versus independent implants has been debated in the literature.4-6 However, it is generally accepted that the use of an overdenture will result in improved mastication, bone maintenance, and nutrition over standard denture use alone.

CASE 1

|

|

| Figure 1. (Case 1) A severely atrophic mandible. Classification B-w ridge. This required block grafting from the Symphysis to allow for implants to be placed in the ABCDE locations as described by Misch (Contemporary Implant Dentistry, third Edition, Mosby) |

Figure 2. With a height of 22 mm from tissue to incisal edge, a hybrid prosthesis was selected so that acrylic could be used for lost tissue reconstruction. A fixed prosthesis would have excessive weight and expense and the cost of pink porcelain and potential bulk fracture precluded use of porcelain for this restoration. |

|

|

|

Figure 3. An approved denture was duplicated in clear acrylic which served a surgical guide to place the 5 implants. |

Figure 4. Ideal implant placement of 5 implants (BioHorizons) according to the ideal prosthesis-driven placement. Note the adequate zone of attached gingival secondary to grafting and alloderm placement around the implants. |

|

|

|

Figure 5. Acrylic (Duralay) impression copings verified impression accuracy prior to fabrication of the metal substructure. Any discrepancy would have necessitated sectioning and re-approximation of segments with a pick up impression. |

Figure 6. The prosthesis mounted on an articulator with impression analogs exposed as a secondary verification of seating accuracy prior to processing of the hybrid prosthesis. (Note: An independent try in with a baseplate and denture teeth was done as an interim step to again check passivity of casting.) |

|

|

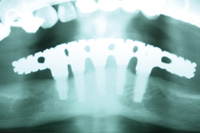

| Figure 7. Radiograph showing the completed prosthesis. |

Figure 8. Left lateral view showing the lingualized occlusion scheme, blend of upper partial teeth to lower prosthesis teeth, and aesthetics of the replaced maxillary anterior bridge. |

|

|

| Figure 9. Preoperative view of patients’ maxillary restorations. |

Figure 10. Postoperative smile displaying correct occlusal vertical dimension, golden proportion and overall final aesthetic. |

|

|

Figure 11. Postoperative full-face view of patient 3 years after hybrid delivery. |

A woman presented to our office for treatment planning. She had been to a dentist who wanted her to invest $20,000 on the restoration of her maxillary arch. This was to include crowns, fixed partial dentures, and the replacement of her lower complete denture.

CASE 2

|

|

|

Figure 12. (Case 2) Cast mandibular bar for 4 implant overdenture with bredent attachments at distal ends of the bar. Bar is milled for hader clips and for a superior metal housing in the overdenture to engage. |

Figure 13. Lower metal reinforced overdenture with 2 Bredent attachments, 3 Hader clips and metal housings milled to fit with the mandibular bar. |

|

| Figure 14. Retracted view of upper denture with lower bar-supported overdenture. |

With this patient, we also began with a knife-edged ridge. This ridge was leveled by osteoplasty, and 4 implants (BioHorizons) were placed between the mental foramina in the A, B, D, and E positions (Figure 12). These corresponded to the 5 available sites between the mental foramen that would allow us to create a fixed bridge, a hybrid, or an overdenture. After the bar was fabricated and checked for passivity of fit, a metal-reinforced overdenture was fabricated to fit intimately over the milled bar. Within the denture (Figure 13), 2 Bredent attachments (green) and 3 Hader clips were embedded into the metal intaglio of the prosthesis. (Note: the metal frame extends to the retromolar pads bilaterally, and acrylic is left in contact with the edentulous ridge for better adhesion of future saddle relines.) While we had originally planned to upgrade this patient to fixed bridgework, she was satisfied with the comfort, biting forces, and feel of the lower prosthesis. As a result, she was then pursuing an upgrade to her upper prosthesis. She was educated that she would continue to lose bone in the edentulous free-end saddle area. However, for the time being, she was allowed the dignity of chewing without a mobile denture. Having gained stability, support, and comfort, all of her phase 1 goals were met. Figure 14 shows the mesial-lingualized occlusion in a retracted view. While discussing the sequence of “upgradability,” it must be realized that upper dentures opposing newly fixed prostheses will “feel” looser. Upper dentures are typically the denture that fits and feels good. That is, of course, until the lower arch becomes rigidly fixated. The allocation of a patient’s financial resources should take into account the concept of “Combination Syndrome.” This phenomenon describes the increased bone loss from pressure opposing the rigidly fixated arch. This arch requires support with implants and a prosthesis so that opposing forces can be offset.7-9 An example of Combination Syndrome would be when people have remaining mandibular teeth that have undergone altered passive eruption, and they have a concomitant flabby ridge in the premaxilla.

CASE 3

|

|

|

Figure 15. (Case 3)Patient at 5 years post-delivery of the overdenture, prior to relining the prosthesis. |

Figure 16. Maxillary 8 implant bar, fabricated in 2 pieces with a dove tail for seating and decreasing casting error. |

|

|

Figure 17. Maxillary Overdenture with metal substructure, cast to fit on the bar with Bredent attachments cast as part of the metal framework. |

This patient underwent extensive treatment due to continually failing dentistry. She was tired of the continual repairs delivered by her previous dentist who had recently treatment planned her for a laser-assisted new attachment procedure ($5,000) and a precision attachment partial denture. This doctor and his team did not accurately assess this patients needs, wants, and desires.

CASE 4

|

|

|

Figure 18. (Case 4) With a lower locator overdenture: consisting of 5 locators and 2 metal copings made to retain the lower canines. Maintenance of the canines will preserve the bone in these future target implant sites for “upgrading” from an overdenture to a hybrid or fixed prosthesis in the future. This prosthesis is metal-reinforced to maintain strength. |

Figure 19. Intraoral view of the implants placed with optimal A-P spread with locator attachments in place. The metal copings were made several years ago. |

|

| Figure 20. Postoperative smile view of completed upper denture and lower locator-retained overdenture. |

This patient presented to our office with 2 failing implants and copings over his canine roots. The lack of an anterior stop caused fulcrums on the posterior implants leading to premature failure. The addition of 5 new implants allowed for a cost-effective interim treatment until more implants and fixed bridgework (or a hybrid prosthesis) could be fabricated. Figure 18 shows the locator attachments with a metal substructure in the lower denture, and Figure 19 shows the 5 locator attachments. Figure 20 demonstrates excellent lip support and the benefits of a neutral zone impression technique.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The cases presented above all highlight various aspects of dental care that have brought patients to their next level. The treatment is not done until the patient has a result with which he/she is happy. When “upgradeable dentistry” is discussed, we must also realize that dentistry must be affordable.

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to Drs. Leonard Machi and John Werwie for the excellent implant surgery and mentorship they have provided for my patients and me. Excellent laboratory support was provided from Valley Dental Arts and Nu-Craft Dental Lab.

References

- Winter R. Upgradeable dentistry: Part 1. Dent Today. 2009;28:82-87.

- Winter R. Upgradable dentistry: Part 2. Dent Today. 2009;28:97-100.

- Misch LS, Misch CE. Denture satisfaction—a patient perspective. Int J Oral Implantol. 1991;7:43-48.

- Chan MF, Johnston C, Howell RA, et al. Prosthetic management of the atrophic mandible using endosseous implants and overdentures: a six year review. Br Dent J. 1995;179:329-337.

- Payne AG, Solomons YF. Mandibular implant-supported overdentures: a prospective evaluation of the burden of prosthodontic maintenance with 3 different attachment systems. Int J Prosthodont. 2000;13:246-253.

- Tang L, Lund JP, Taché R, et al. A within-subject comparison of mandibular long-bar and hybrid implant-supported prostheses: psychometric evaluation and patient preference. J Dent Res. 1997;76:1675-1683.

- Federick DR, Caputo AA. Effects of overdenture retention designs and implant orientations on load transfer characteristics. J Prosthet Dent. 1996;76:624-632.

- Tolstunov L. Combination syndrome: classification and case report. J Oral Implantol. 2007;33:139-151.

- Carlsson GE. Responses of jawbone to pressure. Gerodontology. 2004;21:65-70.

- Cabianca M. Combination syndrome: treatment with dental implants. Implant Dent. 2003;12:300-305.

Dr. Winter is a master and on the board of directors for the Wisconsin Academy of General Dentistry. He is a Fellow and master of the Academy of Dentistry International and the International Congress of Oral Implantology. He is a member of the AAID, ICOI, CDS, ADA, GMDA, AGD, and Alpha Omega and a graduate of the Misch International Implant Institute. He is an international consultant for Dental Health Libraries, a nonprofit Internet information entity. He lectures on “Upgradeable Dentistry” and can be reached via e-mail at rick@winterdental.com for further details or comments.

Disclosure: Dr. Winter reports no conflicts of interest.