This article will highlight some important aspects in the relationship between the dentist and the dental technician along with the impact of today’s healthcare challenges on their respective responsibilities. Among these is access to dental healthcare, the increase in the noninsured and underinsured populations, as well as the changing and increasing needs of the baby-boomer generation.

In 1883, the dental profession had its first dental laboratory pioneer, Dr. W.H. Stowe. Known for his special processes and skills in fabricating prosthetic devices, he concentrated a large portion of his practice constructing appliances for other dentists. The demand for his services initiated dentists’ outsourcing of services for dental prosthetic devices. By 1910, commercial dental laboratories were under the administration of dental technicians.1 The work of the laboratory technician within the dental team went on to become indispensable whenever a prosthesis was indicated in the patient’s treatment plan.

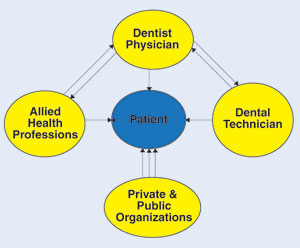

SHARED RESPONSIBILITIES

|

| Figure. This simple diagram illustrates an organizational pattern of some factors that interface in the treatment of a patient. The central image represented by the patient who will present challenges, and or, receive the end results of the interaction/communication between different sections of the healthcare system. All these sections will influence with disproportionate intensity the outcome of treatment. It is the duty of all stakeholders in the system to establish the proper equilibrium for the best treatment of the patient. |

It has been proven by experience that predictable results in prosthodontics depend on a comprehensive oral exam and treatment plan done by the dentist. In performing any comprehensive oral exam it is extremely important that the dentist gets to know the patient as well as his or her treatment expectations.2 Once an impression is poured and/or sent to the laboratory with its corresponding prescription, the responsibility of the dental laboratory technician becomes fundamental in caring for the pa-tient as represented by mounted working models, pictures, bite registrations, and sometimes dental x-rays.

A dental laboratory technician has several primary duties: following instructions and specifications written in the patient’s prescription; good customer relations that include close communication with the dentist (such as initiating phone calls or e-mails if questions arise regarding shade, preferred materials, type and design of an appliance or restoration, etc); identifying defects on the impression or master model received from the dentist; following dental material specifications to minimize distortion; proper infection control of prosthetic devices entering and leaving the dental laboratory; negotiating an agreement related to fees for services rendered and turn-around time, including the method of pick-up and delivery; observance of state board regulations for dental laboratories; and staying abreast of new materials and procedures through ongoing continuing education.

MANY CHALLENGES ARE LOOMING

Challenges brought about by today’s technological advances in dental materials and techniques (ie, pressable ceramics, CAD/CAM technology, digital impression systems, and continuous advances in dental implants) have demanded ongoing continuing education for the dentist and dental laboratory technician. This educational process for dental technicians is of special benefit for the dentist who cannot keep up with all the technical information and may in fact depend upon the dental technician as a consultant in the design or material makeup of the prosthetic appliance prescribed. Opening communication channels through continuing education that are complementary for the dentist and dental technician will result in the best treatment options for the patient. A survey of 114 dental laboratories in the United States revealed that a lack of communication existed between dental technicians and dentists when materials and techniques used for implant fabrication were involved.3

Another challenge is the increase in the uninsured and underinsured populations who are in need of the construction and repair of an increased number of removable prosthetics. The most recent estimate released in August, 2004, showed that the majority of Americans with employer-sponsored insurance plans was decreasing, resulting in an increase of the uninsured population to approximately 45 million.4

The Kaiser Commission on Medi-caid and the Uninsured (KCMU) found that the number of Americans without health insurance increased by 4.6 million from 2001 to 2004, while federal safety net spending fell from $546 million to $498 million during that same period.4 After adjusting for inflation, total spending for medical care of the uninsured increased by 1.3%, while the number of uninsured increased by 11.2%. The commission demonstrated that higher deductibles, premiums, and co-payments can create a financial burden when needed income is not there even for insured families.4 It is also interesting to note the number of people in the uninsured population that actually belong to the work force and contribute to the economy, and yet cannot afford dental health insurance. In addition, insured citizens who carry medical health debts can be limited in their access to dental care. The Commonwealth Biennial Health Insurance Survey revealed that 77 million Americans age 19 years and older, nearly 2 of 5 adults (37%), have difficulty paying their medical bills and/or have accrued medical debt.5

AN INCREASED NEED FOR REMOVABLE PROSTHESES?

The Centers for Disease Control has recognized different threats to the oral health of the adult population in the United States. In adults ages 35 to 44, nearly one third have untreated tooth decay. One in 4 adults over the age of 65 have periodontal disease.6 It is a well-known fact that the absence of primary and preventive dental care increases the number of teeth needing extraction. The uninsured and underinsured citizens do not have the economic capacity to absorb the expense of fixed prosthodontics, leaving them only 2 alternatives: replacement of lost teeth with removable prosthetics or assuming a passive attitude by not replacing missing teeth (with all the natural and negative consequences). All the aforementioned healthcare limitations translate to lack of access to dental care. This in turn will lead to a greater demand for the dentist-dental technician team to fabricate removable prostheses.

Studies show that approximately 60% of patients with full dentures have at least one significant issue with their prostheses. Of this 60%, 50% lack stability, 10% to 18% lack integrity (lack of quality control), and 12% to 42% have retention issues.7

As the baby-boomer generation approaches retirement age, there are serious challenges to different aspects in the organizational structure of many institutions, public and private. This is especially true for the Social Security Administration and healthcare organizations. The baby boomers are targets for marketing programs and are recognized as a group with above-average economic potential. The dental care of this generation will result in an increased demand for removable ap-pliances. Research demonstrates that 70 million baby boomers are heading toward retirement age.8 The American Association of Retired Persons reports that by 2012, one in 5 workers will be 55 years of age or older and the retirement status for baby boomers will exceed age 65.8

The need for removable prosthetics in dental school curricula has been questioned as preventive dentistry philosophies in the population has increased. Research has shown that there will be an increase of adults in need of one or 2 complete dentures, from 33.6 million in 1991, to 37.9 million in 2020. And, although there has been a 30% decrease in edentulous adults in a 30-year period, there will be an increase of 79% in the over-55 age group that will offset this data.9

CONCLUSION

Improved communication channels and a common front to deal with challenges brought by present and future dental healthcare changes will minimize complications in patient treatment options. A trustworthy communication process between the dentist, the patient, and the dental laboratory technician is fundamental for the success of a case. Private and public organizations are major stakeholders in today’s dental healthcare. They have excessive control over patients’ treatment outcomes when out-of-pocket cash is not available (Figure).

The dental profession must not have a tunnel-vision attitude for these looming challenges. The increase in demand for removable prosthetics, either implant or tissue-supported, will require more services from the dental profession backed by dental laboratories for the maintenance of existing removable prostheses either by replacement or repair. The existence of 45 million uninsured persons is a major political issue, and in the meantime, it is a problem that has an effect on the dental health of citizens of all ages in the United States.

References

- National Board for Certification in Dental Laboratory Technology. An overview of history, regulation & organization in dental laboratory technology. http://www.nbccert.org/dent_tech_history.cfm. Accessed March 9, 2008.

- Ratcliff S. The comprehensive oral health evaluation. Pankeydentist.org Web site. www.pankeydentist.org. Accessed October 13, 2007.

- Afsharzand Z, Rashedi B, Petropoulous V. Dentist communication with the dental laboratory for prosthodontic treatment using implants. J Prosthodont. 2006;15:202-207.

- Hoffman C, Holahan J. What is the current population survey telling us about the number of uninsured? The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Kaiser Family Foundation Web site. http://www.kff.org/uninsured/7384.cfm. Published August 24, 2005. Accessed July 29, 2008.

- Doty MM, Edwards JN, Holmgren AL. Seeing red: Americans driven into debt by medical bills. Page 4. The Commonwealth Fund Web site. http://www.illinoiscovered.com/assets/cover_837_Doty_seeing_red_medical_debt.pdf. Published August 2005. Accessed March 9, 2008.

- Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Oral Health. Adult Oral Health page. http://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/topics/adult.htm. Accessed July 29, 2008.

- Sarka RJ. Complete dentures: are they out of phase with current therapy? Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1996;17:940-946.

- Roper ASW. Staying ahead of the curve: the AARP work and career study: research report. Page 22. http://www.aarp.org/research/reference/publicopinions/aresearch-import-416.html. Published September 2002. Accessed October 2, 2007.

- Douglass CW, Shih A, Ostry L. Will there be a need for complete dentures in the United States in 2020? J Prosthet Dent. 2002;87:5-8.

Dr. Prats is a graduate of the University of Puerto Rico, School of Dentistry. He has practiced general dentistry for 30 years and is a Fellow of the Academy of General Dentistry. He completed a masters in health administration and has had experience working as a patient relations specialist and medical terms interpreter at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas, Tex. These experiences were instrumental in developing his interest in future challenges related to the uninsured population. He currently serves as a doctors’ relations specialist at Stern Reed Associates Dental Laboratory, allowing him to view the profession from a doctor-technician perspective. He can be reached at (972) 233-7701 or prats_lorenzo@yahoo.com.