In 2004, the American Cancer Society estimated that 1,368,030 new cases of cancer were diagnosed with 563,700 deaths.1 In 2007 new cancer diagnoses accounted for 1,444,920, with deaths totaling 559,650.2 What this means for you as a clinician, and for your practice, is an increase in the number of patients with a cancer diagnosis and more of your patients being treated for cancer. It is entirely possible that you, a family member, or a friend will come face-to-face with this disease with all its implications.

What does this mean for you, your staff, and your patients? Are you remembering to screen every patient for oral cancer at each appointment? Are you fully prepared to evaluate someone prior to chemotherapy or radiation treatment? Can you actively support a patient who is undergoing therapy for months at a time?

|

|

Illustration by Nathan Zak

|

CANCER IN DAILY LIFE

I am a cancer survivor. While many things in life create change in our routines, cancer seems to turn our world upside down. What was once the exception becomes the norm, and what was once routine becomes the exception. The dictionary defines routine as a regular course or procedure, a chore that we do regularly. In the world of dentistry, it means going to the dentist every 6 months from early childhood, brushing our teeth twice a day or maybe after every meal. Routines often start early in our lives, and we are not even consciously aware that we are following them. For young people today, flossing is taught from an early age. For those of us who are a bit more mature, flossing is hard to incorporate into our routine because we were not taught it was important until we were older.

What happens when something like cancer comes along that not only interrupts our routine, but also leaps into our lives, suddenly, through no control of our own, and demands a new routine? The result is mental chaos! Have you ever tried to listen to a different radio station on your way to work? Or has the roll of paper towels been reversed by someone who does not know the sheets are supposed to come off the top of the roll? It seems to upset our psyche.

One day several years ago, a day that many fear, I was diagnosed with a fairly aggressive form of breast cancer and put on an intensive chemotherapy regimen. I was sick, depressed, bald, and scared, and suddenly all my routines changed. Overnight, illness, once the exception, became the rule. Normal routines became the exception. My world was upside down, and my mind and my life were in chaos.

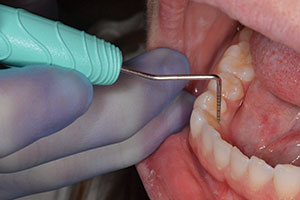

CANCER AND THE DENTAL CHECKUP

Before starting my chemotherapy regimen, I was instructed to go to my dentist—not at 6-month intervals, but at 1- or 2-month intervals. Now, I am not crazy about going to the dentist. As a matter of fact, it was a toss up for me as to which was worse: chemotherapy or a trip to the dentist. I grew up in the era when having a cavity filled was nearly comparable to tying one end of a string around your tooth and the other on a doorknob. As an adult, I learned that the dentist was usually painless, and that the dentist was my friend. I discovered that the dentist played nice music in the office, and the spit bowl had become a thing of the past. However, that did not stop me from flashing back emotionally to childhood and feeling the same dread. So, faced with having to go every 1 or 2 months to create a new dental routine, I thought the doctors had to be kidding!

Why did I need to do this? Mouth sores, a much increased chance of decay, and the need for a special mouthwash are just 3 of many good reasons why I was told to change my routine. It was hard to do. It should not have been: I wanted to take care of the cancer, I wanted to take care of my body, and I wanted to take care of my teeth. But when you feel your life is hanging by a thread, the old routines just feel comfortable. They are like an old pair of slippers. And yet I was told my routines had to change by someone who had no idea what this was doing to my peace of mind.

DENTISTS AND THEIR CANCER PATIENTS

This story has 2 sides: the patient’s side and the clinician’s side. The dental clinicians want their patients to move through this journey with little trouble, so they give more instructions than ever before. This happens at a time when the patient is already receiving hundreds of instructions from doctors, oncologists, and nutritionists. And yet, at the same time, prevention and management of oral complications of cancer and cancer therapy will improve oral function and quality of life.

While patients are warned about possible complications, they really have little or no idea just how extensive the complications can be. Mucositis (an acute oral mucosa reaction), lose of taste, lack of saliva, very thick saliva, an increase in caries, candidiasis, osteonecrosis, and soft-tissue necrosis are some of the most common complications.3

At the very least, most patients will develop mucositis. If it is acute, chemotherapy may have to be suspended for a week. The lack of desire to eat often results in weight loss and weakness. Patients who have not shown any degree of caries activity for years may develop dental decay and varying degrees of disintegration. This condition appears to be due to the lack of saliva as well as to changes in its chemical composition and viscosity due to the radiation therapy. Oral yeast infections of the mouth, by the ever-present Candida albicans fungus, are commonly seen in irradiated patients.

When a patient is on chemotherapy, the most appropriate time to schedule dental treatment is after the patient’s blood counts have recovered, usually just prior to the next scheduled chemotherapy treatments. If oral surgery is required, it should be scheduled to allow 7 to 10 days of healing before the patient’s next treatment.4

While dentists know that the complications of having and treating cancer can be very serious and can have implications for years to come, cancer patients only know that they want to live. As far as the patient is concerned, the primary risk is not dental; it is feeling lousy from the cancer treatment and surviving the cancer itself. The patient is not focused on the risk from possible side effects. The impact on the teeth and mouth are incidental and does not seem as relevant to the patient as it does to the dentist.

How does this balance with the need for the dentist to become an important part of the overall cancer treatment program? I think the most important thing is to try to keep it simple for the patient. Basically, the patient needs to understand he or she is facing risks, yet too much information will just cause emotional overload and possibly rebellion.

ORAL HYGIENE PROGRAM FOR THE CANCER PATIENT

An oral hygiene program must be individualized for each patient and modified throughout therapy according to the patient’s medical status. While it appears obvious that everyone knows how to brush their teeth, those on a cancer treatment program need to be taught very gentle, yet thorough brushing techniques. They should be cautioned about eating crunchy or sharp foods that may damage delicate oral tissues. Tooth-picks should not be used. They should be taught that alcohol-based mouthwashes and full-strength peroxide solutions (and gels) should not be used due to their drying and irritating effects.4 That’s about it. Remember to keep it simple!

The most important element for the patient is not physical, and it is not the dental treatment. The most important element for the patient is emotional. The dentist needs to be more like a parent taking care of a child: just go ahead and do it. The patient does not really need to know why everything is being done.

First and foremost, the dental clinician needs to recognize that he or she is only one in a long chain of command. During this time, patients are overwhelmed emotionally and physically. After a while, more instructions just roll off their back. It is best to give a written regimen for the few steps for dental care along with a simple explanation like, “We just need to make sure there are no unwanted side effects.”

CHEMOTHERAPY AND DENTAL CARE

I wanted to live. I wanted to beat my cancer. I wanted to keep my teeth and not develop mouth sores. So I tried to adapt. However, I was not sure my dentist understood that while this seems routine and textbook for him, it was just one of hundreds of things that turned upside down for me. It is not as if my life was the same day to day and the only interjection was additional trips to the dentist. Everything in my life changed simultaneously.

After each chemotherapy treatment, I could only crawl into my bed and wait for the anti-nausea medicine to kick-in. Many times, it did not work and I found myself sick several times a day. Food was simply not part of my life for 5 days after a treatment. Brushing my teeth twice a day? How could I, when the taste of anything caused instant nausea? For 5 days after treatment, I was in such a dazed state that I hardly knew day from night. Brushing my teeth? Sorry! It just wasn’t going to happen that day—but hopefully tomorrow—and I promised myself I would brush twice as hard. Did it matter? Did the dentist understand what he was asking of me? If I did not eat at all, would my teeth still decay? Probably, but I must admit it was hard to care at the moment. A nagging thought would then go through my head: if I don’t survive, will people come to my funeral and say, “My, too bad she ended up toothless.” My self-esteem could not bear the thought! So, I struggled to the bathroom and brushed. Perhaps I did not always do it perfectly, but at least the attempt was made. If on my next visit to the dentist, I was warned about not brushing well enough, so be it. I felt I had more important things to worry about.

My new routine became chemo one day, bed and oblivion for 4 days, new anti-nausea medicine for 5 days, operate at 50% the next week, then 75% the following week, and finally back for more chemo at week 4. The dentist had to fit in there somewhere. The only time I could eat and really care about my hygiene was week 3, so that is where the dentist had to fit in.

Usually at my “regular” dental checkup, which occurred every month instead of every 6 months, I would get scolded for not taking proper care of my teeth. I was either not flossing enough or I was not brushing properly. I knew they had to do it, and I knew that they were concerned about my overall health and me. And I cared, I really cared, but along with everything else that turned upside down, this new routine was hard to digest.

Did the dentist understand? As you read this, do you understand this world I was living in? I would like to think that you do. I believe that they did, and I am confident that they were concerned. I am confident my welfare was truly in their hearts. They were warm and friendly when I visited, and I believe it was genuine. I also know they knew things that I do not know. I want to compare it to an innocent child who has no idea that touching the hot stove will cause a burn. We as adults know what can happen, but the child has no idea. My dentist and physicians knew what could happen. I, as the innocent patient, did not know. So I was not worried. I let them worry for me. That was their job, not mine.

Fortunately I made it through my 6 months of chemo with little or no long-term dental effects. My life went back to normal once again. My routine went back to normal, and I now actually miss those regular dental visits. Six months between visits seems like a long time to those who have become my friends, to those who supported me through my ordeal. I no longer dread the visit to the dentist, and I look forward to seeing my caring dental professionals.

CONCLUSION

I did not really want to know all that could have gone wrong. I just needed to know that someone else was watching out for me, that someone was going to step in and prevent me from touching the hot stove, and that all I needed to do was show up on time and my dentist would do the rest. They cared. I know that they cared and that was enough. Hmmm, maybe turning my world upside down and upsetting my routine was not so bad after all.

References

- Estimated New Cancer Cases and Deaths by Sex for All Sites, US, 2004. American Cancer Society Web site. http://www.cancer.org/downloads/MED/Page4.pdf. Accessed June 3, 2008.

- Estimated New Cancer Cases and Deaths by Sex for All Sites, US, 2007. American Cancer Society Web site. http://www.cancer.org/downloads/stt/CFF2007EstCsDths07.pdf. Accessed June 3, 2008.

- Rosenbaum EH, Silverman S, Festa B, et al. Mucositis – oral problems and solutions. Cancer Supportive Care Web site. http://www.cancersupportivecare.com/oral.php. Accessed May 18, 2008.

- Patients During Chemotherapy. BC Cancer Agency Web site. http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/ HPI/CancerManagementGuidelines/SupportiveCare/Oral/03PatientsDuringChemotherapy.htm. Accessed June 3, 2008.

Ms. Massie lives in Spokane, Wash, and is an award-winning speaker who draws from her years as an international business executive and her journey through 2 near-fatal illnesses. As a teenager, a rare, life-threatening illness left her paralyzed and confined to a wheelchair for more than 2 years; then she spent 5 years learning to walk again. At the height of her business career, she was diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer, which left her with a renewed sense of living her soul purpose. She is the author of the book I’ll Be Here Tomorrow – Transforming Tragedy Into Triumph, and her mission is to bring peace and joy to the lives of patients, families, and caretakers who are affected by cancer or serious illness. She can be reached at Lynne@turningpointsuccess.com.