Personal protective equipment (PPE) is designed to protect the skin and mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, and mouth of dental healthcare practitioners (DHCP). PPE includes specific clothing or equipment DHCP wear for protection against a hazard. PPE includes but is not limited to gloves, gowns/jackets, surgical masks, face shields, and protective eyewear. Wearing PPE in specific circumstances reduces the risk of occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens.1,2

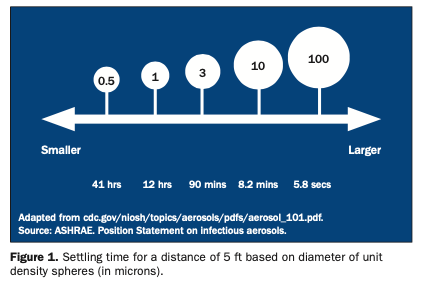

Use of rotary dental and surgical instruments, such as handpieces, ultrasonic scalers, and air-water syringes, generates a spray that primarily contains large-particle droplets of water, saliva, blood, microorganisms, and other debris. Spatter, being relatively heavy, travels short distances and settles down quickly. DHCP are exposed to spatter; spray may contain aerosols, which are small (< 10 mm). Aerosols can remain airborne for extended periods and can be inhaled.1,2

In addition to droplet infection, diseases can be spread by direct and indirect contact. Touching soft tissue or teeth in a patient’s mouth results in direct contact with microorganisms with immediate spread from the source. This gives microorganisms an opportunity to penetrate the body through small breaks or cuts in the skin and around the fingernails of ungloved hands. A second mode of spread is called indirect contact, which can result from injuries with contaminated sharps (eg, needlesticks) and contact with contaminated instruments, equipment, surfaces, and hands. These items and tissues can carry a variety of pathogens, usually because of the presence of blood, saliva, or other secretions from a previous patient.3,4

Gloves prevent contamination of DHCP hands when touching oral tissues or instruments and pieces of equipment soiled with patient blood and saliva. Gloves also reduce the likelihood that microorganisms present on DHCP hands will be transmitted to patients during surgery or patient-care procedures.

FEDERAL AGENCIES

Over the last 20 years, the use of gloves by DHCP has increased markedly. Glove usage is often identified as being “the first line of PPE defense.” Increased glove usage began in the mid 1980s. This behavioral change was initially a response to the emergence of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. During the same time period, a set of blood and body fluids precautions termed “universal precautions” emerged. Under universal precautions, blood and certain body fluids of all patients were to be considered potentially infectious for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and other bloodborne pathogens. Universal precautions are intended to prevent parenteral, mucous membrane, and nonintact skin exposures of healthcare workers to bloodborne pathogens. In addition, immunization with HBV vaccine is recommended as an important adjunct to universal precautions for healthcare workers who have exposures to blood.1,5

Soon, the relevance of universal precautions to other aspects of disease transmission was recognized. And in 1996, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) expanded the concept and changed the term to standard precautions. The standard of care was designed to protect DHCP from all pathogens, not just bloodborne pathogens. Standard precautions apply to contact with blood and all body fluids, secretions, and excretions (except sweat), regardless of whether they contain blood and contact nonintact skin or mucous membranes. Saliva has always been considered a potentially infectious material in dental infection control.1

The new CDC infection control guidelines offer advice as to the best use of gloves.1 Concerning general glove use, the CDC indicates the following:

(1) Wear medical gloves when a potential exists for contacting blood, saliva, other potential infectious materials (OPIM), or mucous membranes.

(2) Wear sterile surgeons’ gloves when performing oral surgical procedures.

(3) Wear a new pair of medical gloves for each patient, remove them promptly after use, and wash hands immediately to avoid transfer of microorganisms to other patients or the environment.

(4) Remove gloves that are torn, cut, or punctured as soon as feasible and wash hands before regloving.

(5) Do not wash surgeons’ or patient examination gloves before use or wash, disinfect, or sterilize gloves for reuse.

(6) Ensure that appropriate gloves in the correct size are readily accessible.

(7) Use appropriate gloves (eg, puncture- or chemical-resistant utility gloves) when cleaning instruments and performing housekeeping tasks involving contact with blood or OPIM.

(8) Consult with glove manufacturers regarding the chemical compatibility of glove materials with hand hygiene products as well as the dental materials being used.

The CDC made no recommendation regarding the effectiveness of wearing 2 pairs of gloves to prevent disease transmission during oral surgical procedures. The majority of studies among healthcare personnel and DHCP have demonstrated a lower frequency of inner glove perforation and visible blood on the surgeon’s hands when double gloves are worn; however, the effectiveness of wearing 2 pairs of gloves in preventing disease transmission has not been demonstrated.1

Gloves are also an important issue for the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). In its Bloodborne Pathogens Standard OSHA mandates that all healthcare workers wear gloves during patient care activities where contact with blood or OPIM may be anticipated.5,6

General recommendations from OSHA indicate that employers shall select and require employees to use appropriate hand protection when employees’ hands are exposed to hazards such as those from skin absorption of harmful substances; severe cuts or lacerations; severe abrasions; punctures; chemical burns; thermal burns; and harmful temperature extremes.5

As for selection, OSHA indicates that employers shall base the selection of the appropriate hand protection on an evaluation of the performance characteristics of the hand protection relative to the task(s) to be performed, conditions present, duration of use, and the hazards and potential hazards identified.5

GLOVE EFFECTIVENESS

Gloves’ effectiveness in preventing contamination of healthcare workers has been repeatedly confirmed.6-9 One study indicated that glove usage reduced the number of bacteria on healthcare workers’ hands by more than 80%.10

However, it is essential that all DHCP understand that wearing gloves does not eliminate the need for appropriate hand hygiene. Gloves cannot completely protect hands against microbial contamination. Wearing gloves cannot totally prevent occupational acquisition of serious pathogens through some type of exposure, such as a needlestick. Glove manufacturing guidelines have resulted in higher quality gloves. However, glove defects can and do occur. Also, gloves can be cut, abraded, or punctured. Glove removal is a possible source of hand contamination.1,6-9

Even though gloves have limitations, they do prevent hand contamination during direct patient contact. Gloves also minimize the hazards of handling instruments, equipment, appliance/prostheses, and impressions contaminated with patient body fluids. Gloves reduce the incidence of nosocomial infections. They also inhibit contamination of patient tissues by organisms present on practitioner hands.1,6,11

GLOVE MATERIALS

Medical gloves fall into 2 main categories—natural rubber latex (NRL) and synthetic. NRL is a tree product found in tropical areas of the world. NRL gloves are the product of a very complex and multistep process, which involves a significant number of chemicals. These include additives to help vulcanize/cross-link the materials. The result is a glove that has strength and elasticity. However, compounds inherent to NRL, produced during processing or added to the final product can be problematic. Increased glove usage results in greater DHCP exposure.7,8 The problem of latex sensitivity has recently been well reviewed.12

Synthetic (manmade) nonlatex materials, depending upon their polymeric composition, can be dipped, molded, or extruded into a final glove product. Synthetic gloves are desirable because they reduce the risk of latex exposure. There are 4 basic types of synthetic (elastomeric) gloves. These include nitrile, neoprene (polychloroprene), thermoplastic elastomers (polyethylene and polyurethane), and solvent-dipped processed types (polyvinyl chloride-PCP or vinyl, polyvinyl chloride copolymer, and block copolymer).6-8

Many synthetic gloves have enhanced chemical or puncture resistance. Some have stretchability similar to latex. The decision between NRL and synthetic gloves involves a number of factors. Selecting gloves is task-specific—the right type of glove for a given situation. As with all PPE, comfort and fit are very important. Glove quality (lack of defects) comes next. A number of other issues (eg, cost, allergen content, tactile sensation) are also important. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulated gloves because they are considered to be medical devices. Only FDA-cleared gloves may be used for patient treatment.1,6,7

SELECTING GLOVES

Surgical gloves were first selected as a form of barrier protection to protect practitioners, not the patient. In 1890 at Johns Hopkins Hospital, William Stewart Halstead began the use of surgical rubber gloves to protect the hands of his scrub nurse, Caroline Hampton. Her skin was negatively affected by the harsh disinfectants used in the surgery. So, this initial use of gloves involved a response to contact dermatitis rather than a way to improve infection control.6-8

Table. Glove Types and Basic Uses.*

* Modified from Reference 1. |

As glove usage increased, a significant decrease in postsurgical infections was quickly noted. Hand barrier protection helped to prevent surgical wound infection. Gloves definitely protected patients and practitioners. They are the standard in all surgical procedures. Gloves are generally task-specific; their selection should be based on the type of procedure to be performed (eg, surgical or patient examination) (Table). Gloves should be selected and worn depending on the task to be performed. Sterile gloves must be worn when performing sterile procedures. Nonsterile (examination) gloves may be worn for other tasks.1-8

Glove selection is dependent upon practitioner needs and wants as well the criteria used by a practice or facility or a selection committee.1-4,13

Practitioners select gloves based on the following:

•the type of procedure planned,

•the anticipated length of the planned procedure,

•the stress and wear-and-tear expected,

•if needed, the possibility of double gloving,

•reaction (sensitivity) of the practitioner and the patient, and

•individual preference.

Facilities or committees often select gloves based on the following:

•physical nature—latex versus synthetic or powdered versus nonpowdered,

•gloves with lower latex protein levels,

•the presence of residual chemical levels,

•the known quality of the manufacturer,

•known chemical resistance, and

•the presence of a wide variety of products (eg, composition and sizes) a manufacturer offers.

Selection may also be influenced by the interaction between a glove and the types of hand hygiene products used. The composition of the gowns worn is also a consideration. Most disposable gowns have special coatings or special fabrics that retard the passage of fluids. This leads to the possibility of gloves sliding down the cuffs of the gowns.1-4,13

Additional information on infection control including the use of gloves is available at the OSAP Web site: osap.org. OSAP has recently published a useful workbook, From Policy to Practice: OSAP’s Guide to the Guidelines, concerning the new CDC infection control guidelines. More information is available at the OSAP website.

References

1. Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, et al. Guidelines for infection control in dental health care settings — 2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-17):1-68. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5217a1.htm. Accessed June 2004.

2. Organization for Safety and Asepsis Procedures. From Policy to Practice: OSAP’s Guide to the Guidelines. Annapolis, Md: Organization for Safety and Asepsis Procedures; 2004:29-38.

3. Miller CH, Palenik CJ. Infection Control and Management of Hazardous Materials for the Dental Team. 3rd ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2004:87-93.

4. American Dental Association. Infection control recommendations for the dental office and the dental laboratory. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:672-680.

5. Occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens; needlestick and other sharps injuries; final rule. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Department of Labor. Final rule; request for comment on the Information Collection (Paperwork) Requirements. Fed Regist. 2001;66:5318-5325.

6. Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology. Glove Information for Healthcare Workers. Washington, DC: APIC; 1998:1-2. Available at: www.apic.org/resc/SearchResult.cfm. Accessed June 2004.

7. Education Module II — Barrier Protection: Choosing Proper Hand Barriers. Red Bank, NJ: Ansell Healthcare, Ansell Education Services; 2002:1-27. Available at: www.ansellhealthcare.com/america/usa/ceu/pdfs/ceu_4.pdf. Accessed June 2004.

8. An Analysis of Gloving Materials, A Self-Study Guide. Red Bank, NJ: Ansell Healthcare, Ansell Education Services; 2003:1-27. Available at: www.ansellhealthcare.com/america/usa/ceu/pdfs/ceu_7.pdf. Accessed June 2004.

9. Palenik CJ. Hand hygiene; bring on the alcohol rubs. Dent Today. Dec 2003;22:44-49.

10. Olsen RJ, Lynch P, Coyle MB, et al. Examination gloves as barriers to hand contamination in clinical practice. JAMA. 1993;270:350-353.

11. Boyce JM, Pittet D. Guideline for hand hygiene in health-care settings: recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51(RR-16):1-45.

12. Hamann CP, Rodgers PA, Sullivan K. Allergic contact dermatitis in dental professionals: effective diagnosis and treatment. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:185-194.

13. Twomey CL. Getting a grasp on the surgical glove market. Infection Control Today. March 2003. Available at: www.infectioncontroltoday.com/articles/331feat1.html. Accessed June 2004.

Dr. Palenik has held over the last 25 years a number of academic and administrative positions at Indiana University School of Dentistry. These include professor of oral microbiology, director of human health and safety, director of central sterilization services, and chairman of the infection control and hazardous materials management committees. Currently he is director of infection control research and services. Dr. Palenik has published 125 articles, more than 290 monographs, 3 books, and 7 book chapters, the majority of which involve infection control and human safety and health. Also, he has provided more than 100 continuing education courses throughout the United States and 8 foreign countries. All questions should be directed to OSAP at office@osap.org.