Over 100 million Americans have moderate to severe periodontal disease, and statistics indicate that only 3% of those having the disease are be-ing treated annually.1 General dentists face the challenge of diagnosing and treating periodontal disease in their practice each day, or getting their patients to accept referral to a periodontist.

Free-running pulsed Nd:YAG lasers have been used for the treatment of periodontitis for more than 18 years.2,3 The PerioLase MPV-7 and Laser Assisted New Attachment Procedure (LANAP) technique/ protocol developed by Drs. Robert Gregg and Delwin McCarthy of Millennium Dental Technologies (MDT) provide practitioners the first Nd:YAG laser with a specific procedure and FDA clearance for cementummediated new attachment to the tooth root surface in the absence of long junctional epithelium. It provides for consistent probing depth reduction, clinical new attachment, and radiographic bone growth for periodontally involved teeth with minimal patient discomfort.4-6

An 8-year retrospective study of the LANAP demonstrated consistent mean pocket depth reduction (40%) and improved bone density (38%). In bone density changes measured by the Emago imaging system, 100% of the cases showed a density in-crease. LANAP was shown to be effective in reducing pocket depth without gingival recession over a 6-month period.7,8

In a human histological study comparing LANAP using the PerioLase MPV-7 to scaling and root planing without using the laser, 12 teeth were removed en bloc and studied histologically. Results demonstrated 100% frequency of cementum-mediated new attachment to periodontally affected tooth roots in all 6 of the LANAP-treated teeth.9 The PerioLase Nd:YAG laser and the pat-ented surgical procedure and protocol (Fig-ure 1) provide very selective thermolytic removal of diseased periodontal epithelium in the pocket without harming healthy connective tissue.9-12 It should be noted that it is essential for clinicians to receive proper training and follow proven protocols before performing any laser procedure. MDT requires mandatory completion of a 3-day lecture and live-surgery course demonstrating technique and patient response before treating patients with the MPV-7 using the LANAP protocol.

Pathogens and cytokines are also selectively destroyed by the light energy, providing an aseptic surgical environment for healing following the laser hemostasis step.9-16 This technique uses selective photothermolysis to remove the sulcular and pocket epithelium while pre-serving healthy connective tissue, literally separating the tissue layers at the level of the reté pegs and ridges.9-12 Mobile teeth (above class I mobility) are splinted (eg, using Ribbond and flow-able composite). Occlusal adjustment to remove interferences, minimize trauma, and provide balance to long axis forces are an important part of the LANAP procedure. Patients are monitored at one week, 30 days, and then every 3 months for periodontal maintenance. No periodontal probing is done for at least 9 months to allow sufficient healing time to the cementum-fiber interface.

LANAP is patterned after the Excisional New Attachment Procedure (ENAP).11,12,17 LANAP replaces the scalpel with a 360-µm quartz fiber. Light energy provided by the free-running pulsed (100 microseconds) Nd:YAG laser is transmitted through the fiber to target areas. The Perio-Lase allows power, pulse duration, and rate of repetition to be varied by the clinician to achieve the desired interaction, from diseased tissue ablation to antiseptic hemostasis. This precise and minimally invasive surgical treatment results in minimal patient discomfort and postsurgical recovery time.

The cases presented here show that the LANAP protocol using the Periolase MPV-7 can provide predictable and often dramatic periodontal treatment results.

CASE NO. 1

|

|

Figure 1. LANAP Protocol. The clinical steps of LANAP: (A) beginning with charting bone topography under anesthesia, (B) the optic fiber is oriented parallel to the root surface, and (C) removal of calcified plaque and calculus adherent to the root surface with EMS ultrasonic scaler. In addition, the bactericidal effects of the FR pulsed Nd:YAG laser plus intraoperative use of topical antibiotics are designed for the reduction of microbiotic pathogens (antisepsis) within the periodontal sulcus and surrounding tissues. (D) A second pass with the 650 micro/sec “long pulse” laser finishes debriding the pocket and achieving hemostasis with a thermal fibrin clot. (E) Gingival tissue is compressed against the root surface to close the pocket and aid with formation and stabilization of a fibrin clot. (F) The wound is stabilized, the teeth are splinted if necessary, and occlusal trauma is minimized by occlusal adjustment to promote healing. Oral hygiene is stressed and continued periodontal maintenance is scheduled. (G) No probing is performed for at least 9 to 12 months. |

|

|

|

Figure 2. Case 1, May 2004: tooth No. 19 pre-LANAP. |

Figure 3. Case 1, May 2004: initial probing. |

A 57-year-old white female presented to our office May 2004 with complaints of “sore gums” and bleeding on brushing. She was referred by an existing patient of record, and stated that she knew she had gum disease, but was a dental phobic due to past traumatic dental experiences. She had visited 2 dentists concerning her condition, where she stated that extractions and conventional periodontal surgery had been recommended. Her medical history revealed a penicillin allergy; she was under a physician’s care for ulcers and sinus allergies; took the medications Zyrtec and Prilosec; and was a nonsmoker.

The patient’s oral hygiene was fair, with generalized calculus present on all teeth. The upper right, upper left, and lower right quadrants were missing posterior teeth. There were several areas of red and edematous gingival tissue. The patient experienced no pain, including percussion tests on all teeth. Radiographs revealed generalized moderate bone loss in all quadrants, with severe bone loss distal to tooth No. 19 (Figure 2). Class I mobility was present on that tooth only. Pulp vitality tests on tooth No. 19 were normal. Periodontal charting using the Florida Probe around 23 teeth (138 sites) revealed generalized moderate-to-deep pockets up to 12 mm (Figure 3). The patient was di-agnosed with generalized moderate-to-severe adult periodontitis. Treat-ment alternatives were discussed, including scaling and root planing, periodontal flap surgery, and LANAP. After explanation of the procedures and expectations, the patient selected LANAP. Informed consent was given, and LANAP was scheduled.

|

|

|

Figure 4. Case 1: initial pass LANAP. |

Figure 5. Case 1: hemostasis pass LANAP. |

Using nitrous oxide analgesia and local anesthetic, LANAP was performed in May 2004 on the upper and lower left quadrants using the modalities as described by MDT. First pass with the fiber was done using the PerioLase short pulse of 150 microsecond pulse duration, 200 millijoules per pulse at 20 Hz and 4.0 Watts measured at the fiber tip (Figure 4). Tooth roots were thoroughly scaled using the EMS piezo-electric scaler with 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate irrigation. Total energy used for both quadrants on the first laser step was 2,285 joules, or an average of 175 joules per tooth. Hemostasis was established using the long pulse setting of 550 micro-seconds, 180 millijoules, at 20Hz and 3.6 Watts measured at the fiber tip (Figure 5). Total energy for the hemostasis step was 720 joules,

or 55 joules per tooth. Total energy used was 3,005 joules. Joules per millimeter of pocket depth was 7.7. Occlusal adjustment was performed to balance and minimize lateral forces on each tooth. No teeth were splinted.

The patient tolerated the procedure very well and left in good condition after review of postoperative instructions, including a prescription for Ibuprofen 800 mg every 6 hours as needed for pain management and osteo-promotion. No antibiotics were prescribed. The patient was told to avoid brushing the surgical sites and to rinse twice daily with chlorhexidine gluconate 0.12%.

At the one-week postoperative check the patient reported very little pain or discomfort from the surgery. The soft tissue was healing well. The patient was given oral hygiene in-structions that included continued chlorhexidine rinses twice daily and avoidance of brushing and flossing the surgical sites until the next visit. Occlusion was again adjusted to balance and minimize traumatic forces. The patient was scheduled for LANAP surgery for the right side the following week.

LANAP was performed on the right side using the same technique as described above. First pass energy used was 1,386 joules, or 138 joules per tooth. Hemostasis energy used was 724 joules, or 72 joules per tooth. Total energy used for the entire protocol was 2,110 joules. Joules per millimeter of pocket depth was 7.6. The occlusion was adjusted to minimize trauma; the patient again tolerated the procedure well with no complications. Postoperative instructions were given and analgesics prescribed as mentioned above. No antibiotics were prescribed. The patient was scheduled for a one-week postoperative visit.

One week later the patient reported minimal discomfort and no complications. The occlusion was again adjusted to balance and minimize lateral forces. The patient was scheduled for a 4-week follow-up visit, at which time she was healing well and reported no complications or bleeding when performing oral hygiene. The gingiva appeared pink and healthy throughout the mouth. The patient was then scheduled for regular 3-month maintenance appointments.

|

|

|

Figure 6. Case 1, May 2005: tooth No. 19, 9 months post-LANAP. |

Figure 7. Case 1, January 2005: 9 months post-LANAP. |

|

|

|

Figure 8. Case 1, May 2007: tooth No. 19, 3 years post-LANAP. |

Figure 9. Case 1, May 2007: 3 years post-LANAP. |

On a return visit to the office in January of 2005, the patient continued to report no pain or bleeding of the gums. The gingiva still appeared pink and healthy throughout. Plaque and light calculus were present on the lower anterior teeth. No appreciable mobility was observed on any teeth. Radiographs revealed dramatic bone growth distal to tooth No. 19 and pocket reduction from 12 mm to 1 mm (Figure 6). Periodontal ligament width appeared normal and the tooth tested vital. Periodontal maintenance was performed. The patient was reappointed for continued maintenance and follow-up.

Probing was performed using the Florida Probe, revealing only one pocket depth of 4mm distal to tooth No. 20. All other probe depths were 3 mm or less (Figure 7). No mobility was present on any teeth. Pulp vitality tests on tooth No. 19 remained normal. Initial probing of this patient showed 104 sites (75%) greater than or equal to 4 mm. Probing depths at one year postoperative showed 0 sites greater than or equal to 4 mm. Mean probing depth change (MPDC) was calculated by finding the mean differences in probing depths from baseline to follow-up. The MPDC for this patient showed an average reduction of 68.39%.

The patient continues to remain stable with routine periodontal maintenance in pocket depth and on radiographs to date (Figures 8 and 9).

CASE NO. 2

|

|

|

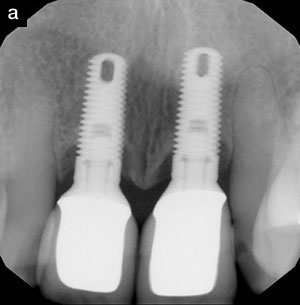

Figure 10. Case 2, February 2003: initial radiograph tooth No. 21. |

Figure 11. Case 2, March 2003: initial probing. |

|

|

|

Figure 12. Case 2, December 2004: probing 10 months post-LANAP. |

Figure 13. Case 2, December 2004: tooth No. 21, 10 months post-LANAP. |

|

|

|

Figure 14. Case 2, April 2007: tooth No. 21, 4 years post-LANAP. |

Figure 15. Case 2, April 2007: 4 years post-LANAP. |

A 51-year-old male presented to the office for periodontal therapy consultation in January of 2003. The patient reported a prior history of periodontal flap surgery in 1995. The patient had an unremarkable medical history, but smoked 10 to 12 cigarettes daily. The patient’s oral hygiene was fair, and moderate calculus was present along with generalized tobacco staining. Tooth No. 10 was missing and replaced by a fixed bridge. All third molars had been removed previously. The gingival tissues were inflamed and edematous, especially around tooth No. 21 where the patient reported he had put aspirin to “help with infection.” Tooth No. 21 exhibited bone loss (Figure 10), class II mobility, and slight pain on percussion, but tooth vitality tests were in the normal range. Full-mouth radiographs revealed generalized bone loss around all teeth. Initial probing depths without anesthesia revealed pockets ranging from 3 to 8 mm, and bleeding was evident on probing (Figure 11). The patient was diagnosed with moderate-to-severe adult periodontitis. The prognosis was guarded due to his smoking habit. The patient was given treatment alternatives that included scaling and root planing, conventional flap surgery, and LANAP. The patient desired LANAP; informed consent was given, and LANAP was scheduled for the upper and lower left quadrants.

Under local anesthesia, the sequential steps of the LANAP protocol were performed. Settings for this patient were a pulse width of 150 microseconds, 200 millijoules per pulse, 20 Hz and 4.0 Watts measured at the fiber tip for the first laser application, and the longer pulse duration setting of 550 microseconds, 180 millijoules per pulse, 20 Hz, and 3.6 Watts for the hemostasis setting. First pass energy used for both quadrants was 1,463 joules, or 112 joules per tooth. Total energy used for hemostasis was 888 joules, or 68 joules per tooth. Total energy used was 2351 joules, and 5.5 joules per millimeter of pocket depth. The occlusion was adjusted to balance forces and remove in-terferences. Because the patient smoked, COE-PAK periodontal dressing (GC AMERICA) was placed. Chlorhexidine gluconate 0.12% rinses were prescribed twice daily along with Ibuprofen 800 mg as needed for pain and osteo-promotion. No antibiotics were prescribed.

The patient returned one week later for a postoperative check and dressing removal. The gingival tissues were healing well, and the patient reported no complications and minimal postoperative discomfort. The occlusion was again adjusted for reasons stated above.

LANAP was performed one week later on the right side. The same settings and treatment sequence were used as described above. First pass energy total was 2,211 joules, or 157 joules per tooth. A total of 729 joules were used, or 52 joules per tooth for the hemostatic step. Total energy used was 2940 joules, and 8.0 joules per millimeter of pocket depth. Occlusal adjustment was performed to minimize trauma as previously mentioned. COE-PAK was placed, and chlorhexidine gluconate 0.12% and Ibuprofen 800 mg were prescribed as described earlier. No antibiotics were prescribed.

The patient returned for a 7-day postoperative check, and the gin-gival tissue was healing well in all quadrants. The patient again had minimal postoperative discomfort and reported taking pain medication only one day following surgery. Occlusion was adjusted to re-move interferences. Oral hygiene instructions were given as previously described. The patient was re-appointed for a 30-day postoperative visit.

The 30-day evaluation revealed pink, healthy tissue in all quadrants. The patient reported no discomfort or bleeding when brushing. Occlusal adjustment was again performed to balance forces and remove interferences. The patient was re-appointed for routine periodontal maintenance at 3-month intervals.

At a 10-month postoperative treatment, radiographs and periodontal evaluation (using the Florida Probe) revealed significant pocket depth reduction (Figure 12). The patient’s tissue was pink and healthy throughout. Tooth No. 21 had stabilized, with no mobility present. Significant bone regeneration was observed on the radiographs (Figure 13).

The gingiva continued to remain pink and healthy in spite of only fair oral hygiene and continued smoking. The patient reported no discomfort or bleeding upon brushing. He is receiving periodontal maintenance at regular 3-month intervals.

Initial probing depths of this patient revealed 124 sites with pockets greater than or equal to 4 mm. Probing depths taken 12 months postoperative revealed 2 sites greater than or equal to 4 mm. MPDC for this patient was 64.95%.

The patient continues to remain stable with routine periodontal maintenance on probing and radiographs to date (Figures 14 and 15).

DISCUSSION

Although presented as specific examples, these 2 clinical cases demonstrate the efficacy of LANAP using the PerioLase MPV-7. The results are consistent with past case studies and university research using the pulsed Nd:YAG laser as a legitimate and effective modality for the treatment of moderate-to-severe adult periodontitis in a gen-eral dentist practice.3,8,12 These cases are also consistent with the studies previously reported using the LANAP procedure.8,12 Both of these cases show dramatic bone regeneration and significant periodontal pocket reduction following LANAP treatment.

These clinical cases appear consistent with histological results of new cementum mediated attachment in the absence of long-junctional epithelium to tooth roots as a proof-of-principle.8 Our office has seen consistent clinical results using the PerioLase for LANAP for over 4 years. Both cases presented here continue to exhibit stable and healthy periodontium at routine maintenance visits at this writing.

CONCLUSION

More independent, controlled, blinded studies are indicated for further comparison and understanding of treatment results using the pulsed Nd:YAG versus conventional surgery. Our office has observed consistent positive clinical outcomes from the bactericidal effects and hemolytic seal that are unique to the pulsed Nd:YAG PerioLase MPV-7 laser. This allows the body to regenerate new tissues in this favorable environment by the selective removal of diseased periodontal tissue and bacteria following the LANAP protocols. LANAP should be considered as a worthwhile and effective treatment of cases of moderate-to-severe periodontal disease, and as a treatment alternative by non-LANAP clinicians in their informed consents.

General dentists treating periodontal disease requiring surgical intervention should consider using this modality due to minimal invasion, predictable results, minor postoperative pain, and in-creased treatment acceptance as compared to conventional periodontal surgery.

References

- Dental lasers in the 21st century. 21st Century Dental Web site. http://www.21stcenturydental.com/smith/PeriolaserfromLares.htm. Accessed January 2, 2008.

- Myers TD, Myers WD, Stone RM. First soft tissue study utilizing a pulsed Nd:YAG dental laser. Northwest Dent. 1989;68:14-17.

- White JM, Goodis HE, Rose CL. Use of the pulsed Nd:YAG laser for intraoral soft tissue surgery. Lasers Surg Med. 1991;11:455-461.

- Gregg RH II, McCarthy D. Laser periodontal therapy: case reports. Dent Today. Oct 2001;20:74-81.

- Gregg RH II, McCarthy D. Laser periodontal therapy for bone regeneration. Dent Today. May 2002;21:54-59.

- 501(k)s final decisions rendered for July 2004 (PerioLase MPV-7, 510(k) number K030290). US FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health Web site. http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/510k/sumjul04.html. Updated August 9, 2004. Accessed January 2, 2008.

- Harris DM. Dosimetry for laser sulcular debridement. Laser Surg Med. 2003;33:217-218.

- Harris DM, Gregg RH II, McCarthy DK, et al. Laser-assisted new attachment procedure in private practice. Gen Dent. 2004;52:396-403.

- Yukna RA, Evans GH, Vastardis S, et al. Human periodontal regeneration following the laser assisted new attachment procedure. Paper presented at: IADR/AADR/CADR 82nd General Session; March 10-13, 2004; Honolulu, HI. Abstract 2411. http://iadr.confex.com/iadr/2004Hawaii/techprogram/abstract_47642.htm. Accessed January 2, 2008.

- Neill ME, Mellonig JT. Clinical efficacy of the Nd:YAG laser for combination periodontitis therapy. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1997;9(suppl):1-5.

- Gregg RH, McCarthy DK. Laser ENAP for periodontal ligament regeneration. Dent Today. 1998;17:86-89.

- Gregg RH, McCarthy DK. Laser ENAP for periodontal bone regeneration. Dent Today. 1998;17:88-91.

- Midda M, Renton-Harper P. Lasers in dentistry. Br Dent J. 1991;170:343-346.

- Moritz A, Schoop U, Goharkhay K, et al. The bactericidal effect of Nd:YAG, Ho:YAG, and Er:YAG laser irradiation in the root canal: an in vitro comparison. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 1999;17:161-164.

- Whitters CJ, Macfarlane TW, MacKenzie D, et al. The bactericidal activity of pulsed Nd:YAG laser radiation in vitro. Lasers Med Sci. 1994;9:297-303.

- Harris DM. Ablation of Porphyromonas gingivalis in vitro with pulsed dental lasers. Paper presented at: 32nd Annual Meeting and Exhibition of the AADR; March 12-15, 2003; San Antonio, TX. Abstract 855. http://iadr.confex.com/iadr/2003SanAnton/techprogram/abstract_27983.htm. Accessed January 2, 2008.

- Yukna RA, Bowers GM, Lawrence JJ, et al. A clinical study of healing in humans following the excisional new attachment procedure. J Periodontol. 1976;47:696-700.

Dr. Long received his BA in Zoology and Biochemistry from the University of Missouri in 1975, and is a 1979 graduate of UMKC School of Dentistry. He has been in private practice as a general dentist in Vandalia, Mo, for 25 years. He is a member of the American Dental Association, Academy of General Dentistry, American Orthodontic Society, Show-Me Study Club, Texas Academy of Laser Dentistry, and American Academy of Cranio Facial Pain, and currently is a trainer and clinical instructor for the Institute of Advanced Laser Dentistry. He has lectured in several states on laser dentistry and is an author of articles on the clinical use of the Nd:YAG laser in dentistry. He can be reached at (573) 594-6166 or clongdds@vandaliamo.net.