Once proper patient evaluation techniques have been implemented and a working differential diagnosis has been created, the clinician can start treatment planning for the temporomandibular disorder (TMD) patient. This is not an easy task, primarily due to the wide array of treatment options currently available.1 In the second and final part of this article, focus will be placed on various treatment modalities for TMD.

TREATMENT

Treatment goals for TMDs are decreasing pain, restoring normal range of motion, and restoring normal masticatory and jaw function. Many TMDs can be cyclical and self-limiting, with periods of complete remission of symptoms. Thus, initial treatment should emphasize a conservative and reversible approach. Primary treatment options include (1) home care (self-care), (2) medical care (nonsurgical care), and (3) surgical care

HOME CARE (SELF-CARE)

Home care generally represents the initial approach to TMD management, at least as part of a more extensive treatment plan. Patient education is a crucial aspect of home care and is one of the most subtle and under-appreciated yet effective treatments for TMDs. Informing and reassuring patients regarding their condition and presenting symptoms may alleviate a great deal of anxiety. In fact, a number of patients report feeling less pain immediately after their initial patient education/counseling visit, perhaps attributable to an immediate reduction in tension-related parafunctional activity.

A successful home care program consists of resting the masticatory muscles by limiting jaw movements, parafunctional habit modification, emphasizing a soft diet, and moist heat and/or ice therapy.2 Muscle rest may involve limited jaw activity (eg, reduced talking, chewing, and yawning) for the treatment duration and perhaps even after symptoms have resolved as a preventative measure. Patients may have a diurnal (daytime) parafunctional habit (clenching, grinding, posturing) that often is not conscious. Patient education and understanding of the physiological rest position (lips together, teeth apart) is imperative in reducing and eventually halting the daytime activity that contributes to the progression of TMDs. If asked to pay attention to their jaw position over time, many patients will return for follow-up with the recognition that they are in fact engaging in some jaw activity that contributes to their symptoms. Additionally, suggesting habit-controlling cues may be helpful in reminding patients throughout the day to check the position of their bite. As an example, saying the letter n throughout the day can remind patients to unclench or discontinue grinding their teeth. Also, a soft diet is crucial to muscle and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain management so that the condition is not exacerbated while treatment is provided. Finally, a trial of moist heat and/or ice therapy overlying the painful areas of the face, head, and neck can be recommended. Usually, moist heat tends to work better for muscle pain or tension by increasing circulation and relaxing involved muscles, and ice tends to work better for TMJ capsulitis by reducing inflammatory symptoms.

MEDICAL (NONSURGICAL) CARE

Physical Therapy

Physical therapy can be performed by an experienced physical therapist or can be provided by a qualified clinician who is treating the TMD. The consistency and regularity of the exercises are critical for achieving a therapeutic effect. Thus, at the outset of treatment planning, an agreement between practitioner and patient regarding compliance will aid in patients understanding of their roles and responsibilities in treatment. Primary goals of the physical medicine component of treatment are to stretch chronically fatigued and contracted muscles, increase range of motion, and reduce muscular trigger point activity.3,4 Some commonly used exercises to treat TMJ-associated muscle disorders include (1) n-stretching (placing the tip of the tongue on the roof of the mouth and stretching the jaw), (2) chin-to-chest exercises (gently pulling the head forward, bringing the chin toward the chest), and (3) head tilts (turning the head to one side and then tilting it posteriorly). These exercises are most effective if done regularly (4 to 6 times per day). In addition, moist heat application for 10 to 15 minutes followed by ethyl chloride or fluoromethane spray prior to stretching the muscles is helpful. The vapo-coolant spray provides a temporary anesthesia effect to the muscles so a more intense stretch can be achieved without pain. Patients can expect an even higher likelihood of treatment success if biofeedback training or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is added to a strict stretching regimen.

Pharmacotherapy

Commonly used pharmacological agents for the treatment of TMDs include analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), local anesthetics, corticosteroids, muscle relaxants, and antidepressants.5-7 The analgesics and corticosteroids are indicated for acute TMD pain; the NSAIDs, local anesthetics, and muscle relaxants are indicated for both acute and chronic conditions; and tricyclic antidepressants are usually indicated more for chronic TMD pain with associated muscle tension headaches.5,7 Clinicians should always consult the Physicians Desk Reference for proper dosing, side effects, and drug interactions, and make decisions regarding pharmacological treatment based on individual patient medical history and comorbidity. Also, referral to the proper specialist should be made in complex TMD cases.

NSAIDs

NSAIDs are indicated for mild-to-moderate acute inflammatory conditions. Commonly used NSAIDs are ibuprofen (Motrin) and naproxen (Naprosyn). NSAIDs may be prescribed for a minimum of 2 weeks with time-contingent usage as opposed to a dosing based on the presence of pain.6 Long-term NSAID use is not recommended as long as the parafunctional activity causing the inflammatory process can be reduced. In some chronic arthritic cases, long-term NSAIDs such as the COX-2 inhibitors (Celebrex, Vioxx), may be considered. However, possible side effects (ie, GI upset) should be taken into account.

Local Anesthetics

Local anesthetics are primarily used when a myofascial trigger point is present. Myofascial trigger points are usually detected in the muscles of mastication but can also be found in numerous other muscles such as splenius capitus and upper trapezius. One percent Procaine (1 cc) is recommended due to its low toxicity to muscles. However, studies have shown that dry needling of the muscle site may play a prominent role in breaking up the trigger point, with the anesthetic functioning more for pain control. Muscles may be sore for the first 48 hours after the injection, but generally should be less tender after that. The efficacy of trigger-point injections is highly variable and dependent for the most part on the patients compliance with a strict physical therapy regimen in conjunction with the injection. In addition, local anesthetics can be used to block the suspected source of pain in order to confirm a diagnosis.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids may be used for acute and chronic TMD symptoms. These medications are used enterally as well as injected directly into the joint space. Systemic steroids may be prescribed for the duration of a week. It is suggested that a steroid TMJ injection should be performed when all previous conservative treatments have not worked and the joint is still acutely inflamed.9 Tomograms of the TMJ or other radiographic studies are required prior to injecting into the joint space. A long-term study has shown that intra-articular corticosteroid injection has demonstrated a significant reduction in pain.10 However, the number of steroid injections should be carefully considered due to the possibility of bone resorption in the site of injection.

Muscle Relaxants

Muscle relaxants may be prescribed for muscle tension associated with TMDs. Commonly, they are taken at night before bed because of associated drowsiness. Thus, for patients with poor sleep patterns, these drugs are particularly helpful in alleviating insomnia in addition to their muscle-relaxing effects. A commonly used muscle relaxant is cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril), started at lower dosages and gradually increased until the patient starts noticing relief of symptoms or starts developing side effects. Muscle relaxants tend to be used for the more acute presentation of muscle tension.

Antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline (Elavil) and nortriptyline (Pamelor) may be used for more chronic myofascial pain syndrome. In addition, they can be prescribed for the TMD patient that has tension-type headaches, depression, poor sleep, and/or poor appetite. It is important to inform the patient that the medication will not usually have antidepressive effects when prescribed at the dosages that are usually necessary to treat muscle pain and/or headaches. Nortriptyline or amitriptyline should be gradually tapered up until the desired therapeutic effect is achieved or side effects such as drowsiness, dry mouth, or weight gain develop. Caution should be used in patients who have comorbid heart conditions, concurrent psychotropic use, and/or psychiatric illness (eg, bipolar disorder).

Orthopedic Appliance Therapy Stabilization Appliance

Stabilization appliances (flat-plane splints) are utilized for the purpose of unloading the joints, equally distributing the forces, reducing the forces placed on the masticatory muscles, and protecting the occlusal surfaces of the teeth from chronic nocturnal bruxing. Usually, the patient is instructed to wear the splint only at night as long as parafunctional activity is controlled during the day with education and bite relation awareness. The splint should cover all of the maxillary or mandibular teeth and have bilateral posterior contacts with little to no anterior contacts. In addition, bilateral ball clasps may be incorporated into the splint for added retention. The stabilization appliance should feel comfortable to the patient at the time of try-in and be re-evaluated in a week. Adjustments should continue every 3 to 6 months because of changes that may result in the form and function of the splint from chronic bruxing.

Anterior Repositioning Appliance

Anterior repositioning splint prescription varies among clinicians, but is usually utilized for the chronic, intermittent closed-locking patient. With the possibility of permanent occlusal and bite changes with long-term use of repositioning appliances, short-term (6 weeks) use of this appliance is strongly recommended. If bite changes start to develop, the patient should be instructed to discontinue the use of the splint, and the splint may need to be converted to a stabilization nonrepositioning appliance. A few patients may experience increased pain with the use of a splint. In this case, the splint as well as the initial diagnosis should be re-evaluated. If the pain persists, discontinuation of splint therapy is recommended.

Surgical Therapy

Surgical therapy for TMD patients is recommended primarily for those that have tried conservative treatments without resolution of symptoms. Surgical recommendations (ie, arthrocentesis, arthroscopy) will depend on the degree of pathology as well as the result of previous conservative treatments. Also, consideration should be given to the patients extent of impairment and their compliance with previous non-surgical treatment modalities. Working closely with an oral and maxillofacial surgeon who has expertise with TMJ surgery is strongly recommended.

Arthrocentesis

Arthrocentesis involves irrigation of the joint with lactated Ringers solution or saline. In certain acutely inflammatory joint conditions, steroid injection may follow arthrocentesis. This procedure is often followed by mandibular manipulation and is recommended for patients who have unresolving joint restrictions and for those individuals who have developed an acute or chronic closed lock.11 It is recommended that the patient have a stabilization or repositioning splint ready to be delivered immediately following the procedure. The procedure may need to be repeated if the lock recurs, and the patient must be reminded to avoid activities that cause locking.

Arthroscopy

Arthroscopy is direct visualization of a joint with an endoscope. It is performed by an oral and maxillofacial surgeon mainly in the upper joint space and is recommended primarily for lysis and lavage and also for ablation of adhesions and biopsy.12 An MRI of the joint is needed prior to the arthroscopic procedure. It is crucial to keep the procedure as brief and atraumatic as possible.

Arthrotomy

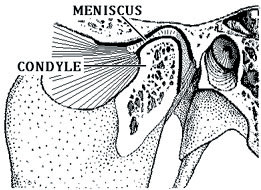

TMJ arthrotomy is an open surgical intervention performed by an oral surgeon. It is recommended for severe osseous pathology involving the TMJ, such as ankylosis and severe osteoarthritis that has not responded to conservative treatments.13 It is crucial to work closely with an experienced TMJ surgeon to assess the necessity of this procedure. Open surgical procedures include disk repair (diskoplasty), disk removal (diskectomy) with or without replacement and disk repositioning, and arthroplastic procedures such as condylar repair and removal (condylectomy).

SUMMARY

Table 1. Differential diagnosis of orofacial pain.

|

TMDs are only one of a host of different conditions that are part of the broader category of chronic orofacial pain disorders and dysfunctions. Due to multifactorial etiologies, it is imperative to adopt a multidisciplinary approach when evaluating and treating these patients. Table 1 lists the various conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis of orofacial pain disorders.

References

1. Okeson JP. Orofacial Pain: Guidelines for Assessment, Diagnosis, and Management. Chicago, Ill: Quintessence Publishing; 1996.

2. Randolph CS, Greene CS, Moretti R, et al. Conservative management of temporomandibular disorders: a posttreatment comparison between patients from a university clinic and from private practice. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1990;98:77-82.

3. Carlson CR, Okeson JP, Falace DA, et al. Stretch-based relaxation and the reduction of EMG activity among masticatory muscle pain patients. J Craniomandib Disord. 1991;5:205-212.

4. Clark GT, Adachi NY, Dornan MR. Physical medicine procedures affect temporomandibular disorders: a review. J Am Dent Assoc. 1990;

121:151-162.

5. Gangarosa LP, Mahan PE. Pharmacologic management of TMJ-MPDS. Ear Nose Throat J. 1982;

61:670-678.

6. Gregg JM. Pharmacologic management of myofascial pain dysfunction. Am Dent Assoc. 1983:167-173.

7. Gregg JM, Rugh JD. Pharmacological therapy. In: Mohl ND, Zarb GA, Carlsson GE, et al, eds. A Textbook of Occlusion. Chicago, Ill: Quintessence; 1988:351-375.

8. Kopp S, Carlsson GE, Haraldson T, Wenneberg B. Long-term effect of intra-articular injections of sodium hyaluronate and corticosteroid on temporomandibular joint arthritis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;45(11):929-935.

9. Kopp S, Carlsson GE, Haraldson T, et al. Long-term effect of intra-articular injections of a glucocorticosteroid into the TMJ: a clinical and radiographic 8-year follow-up. J Craniomandib Disord. 1991;5:11-18.

10. Dimitroulis G, Dolwick MF, Martinez A. Temporomandibular joint arthrocentesis and lavage for the treatment of closed lock: a follow-up study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;33:23-27.

11. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. Position paper on TMJ arthroscopy. Rosemont, Ill: American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons; 1988.

12. Buckley MJ, Merrill RG, Braun TW. Surgical management of internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51(suppl 1):20-27.

Dr. Uyanik completed his DDS degree at SUNY Buffalo School of Dental Medicine and then went on to a 2-year post-doctoral residency program in orofacial pain at UCLA. Upon completion of his post-doctoral training, he obtained boardcertification from the American Board of Orofacial Pain and is currently a member of the house staff at St. Barnabas Hospital working with residents in the diagnosis and treatment of orofacial pain disorders. He was recently appointed as clinical assistant professor at Columbia School of Dental and Oral Surgery in the Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery as well as director of the Center for Oral, Facial and Head Pain. Dr. Uyanik is currently investigating the effects of low-level diode laser therapy on TMJ arthralgia and myofascial pain syndrome. He can be reached at (212) 305-7626 or e-mail jmu2101@columbia.edu.