|

|

The boy was buried with around 90 amber beads. Chemical tests on teeth from an ancient burial near Stonehenge indicate that the person in the grave grew up around the Mediterranean Sea. |

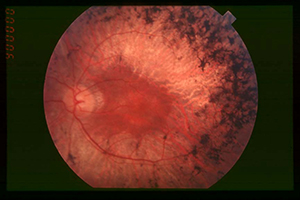

The bones belong to a teenager who died 3,550 years ago and was buried with a distinctive amber necklace.

The conclusions come from analysis of different forms of the elements oxygen and strontium in his tooth enamel.

Analysis on a previous skeleton found near Stonehenge showed that that person was also a migrant to the area.

The findings will be discussed at a science symposium in London to mark the 175th anniversary of the British Geological Survey (BGS).

The “Boy with the Amber Necklace,” as he is known to archaeologists, was found in 2005, about 5 km southeast of Stonehenge on Boscombe Down.

The remains of the teenager were discovered next to a Bronze Age burial mound during roadwork for military housing.

“He’s around 14 or 15 years old and he’s buried with this beautiful necklace,” said Professor Jane Evans, head of archaeological science for the BGS. “The position of his burial, the fact he’s near Stonehenge, and the necklace all suggest he’s of significant status.”

Dr. Andrew Fitzpatrick, of Wessex Archaeology, backed this interpretation: “Amber necklaces are not common finds,” he told BBC News. “Most archaeologists would say that when you find burials like this … people who can get these rare and exotic materials are people of some importance.”

Chemical record

Professor Evans likened Stonehenge in the Bronze Age to Westminster Abbey today—a place where the “great and the good” were buried.

Tooth enamel forms in a child’s first few years, so it stores a chemical record of the environment in which the individual grew up.

Two chemical elements found in enamel—oxygen and strontium—exist in different forms, or isotopes. The ratios of these isotopes found in enamel are particularly informative to archaeologists.

Most oxygen in teeth and bone comes from drinking water—which is itself derived from rain or snow.

In warm climates, drinking water contains a higher ratio of heavy oxygen (O-18) to light oxygen (O-16) than in cold climates. So comparing the oxygen isotope ratio in teeth with that of drinking water from different regions can provide information about the climate in which a person was raised.

Most rocks carry a small amount of the element strontium (Sr), and the ratio of strontium 87 and strontium 86 isotopes varies according to local geology.

The isotope ratio of strontium in a person’s teeth can provide information on the geological setting where that individual lived in childhood.

By combining the techniques, archaeologists can gather data pointing to regions where a person may have been raised.

Tests carried out several years ago on another burial known as the “Amesbury Archer“ show that he was raised in a colder climate than that found in Britain.

Analysis of the strontium and oxygen isotopes in his teeth showed that his most likely childhood origin was in the Alpine foothills of Germany.

“Isotope analysis of tooth enamel from both these people shows that the two individuals provide a contrast in origin, which highlights the diversity of people who came to Stonehenge from across Europe,” Professor Evans said.

The Amesbury Archer was discovered around 5 km from Stonehenge. His is a rich Copper Age or early Bronze Age burial, and contains some of the earliest gold and copper objects found in Britain. He lived about 4,300 years ago, some 800 years earlier than the Boscombe Down boy.

The archer arrived at a time when metallurgy was becoming established in Britain; he was a metal worker, which meant he possessed rare skills.

“We see the beginning of the Bronze Age as a period of great mobility across Europe. People, ideas, objects are all moving very fast for a century or two,” Dr. Fitzpatrick said. “At the time when the boy with the amber necklace was buried, there are really no new technologies coming in [to Britain] … We need to turn to look at why groups of people—because this is a youngster—are making long journeys.”

He speculated: “They may be travelling within family groups … They may be coming to visit Stonehenge because it was an incredibly famous and important place, as it is today. But we don’t know the answer.”

Other people who visited Stonehenge from afar were the Boscombe Bowmen, individuals from a collective Bronze Age grave. Isotope analysis suggests these people could have come from Wales or Brittany, if not further afield.

The research is being prepared for publication in a collection of research papers on Stonehenge.

|