INTRODUCTION

Our dental school educations definitely encompassed a multitude of oral presentations, both hard- and soft-tissue, to identify, study, and treat. During a clinic rotation, you may have had the opportunity to view cases that combined real-time symptoms and classroom knowledge. Those patients’ cases were unique in how they came alive and would imbed in your memory for future professional practice. Other presentations remained remote and were never identified other than in a pathology or restorative textbook. As a student throughout this learning process, you would ask yourself, “Will I ever see that in my practice? Does it always look like this? Are there variations? What is the best approach? When do I refer the case? What are the steps in treating a multifactorial case?”

What Your Practice Uncovers

As you settle into practicing dentistry, the answers to those early learning questions become more noteworthy, especially as you encounter patients’ conditions and health histories. Your experience grows, and, with more clinical expertise, your ability to understand a patient’s journey and discover other imposing factors on their dental health increases. Regardless, it is imperative, more than ever, for dental professionals to take complete histories not only of the medical and dental components but also to uncover behavioral aspects. The clinician must gather all the needed information that is required to make a solid diagnosis that will result in the proper treatment.

The Effect of Acid on the Oral Environment

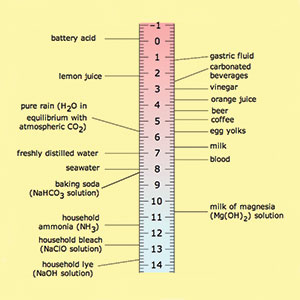

Dental erosion is the irreversible loss or wear of hard tissue by acids not caused by bacteria (Figure 1). The oral environment is in a constant battle for pH balance against chemicals and bacteria. Enamel’s carbonated calcium structure has been estimated to dissolve at a pH of 5.5. The hydroxyapatite composition balance relies on saliva that contains various phosphate and calcium ions for defense and buffering.1

|

|

| Figure 1. Dental erosion. | Figure 2. A pH chart. |

Dental erosion may be caused extrinsically from diet and/or intrinsically from acid reflux or excessive vomiting. In particular, carbonated soft drinks, sports drinks, and other acidic beverages—especially those with added citrus—are prominent offenders. Many of these beverages range from a level 2 to 3 pH, so it is easy to understand the damage that can ensue. The result of these drinks is a chemically induced invasion, causing erosion2 (Figure 2).

Structurally, the enamel suffers from permanent weakening as the acid washes relentlessly over the enamel rods. The erosion also exposes dentin and teeth to further damages, such as decay caused by bacteria and chipping or cracking caused by biting or chewing. The exposure of dentin can be particularly challenging due to aesthetics, sensitivity, and potential caries.2,3

Lifestyle

Extrinsic factors appear to be a modern-day phenomenon, especially with the introduction and consumption of diet sodas in our diet today. Beverages are, in fact, largely responsible for dental erosion.4,5 Besides carbonated beverage consumption, other contributing factors to consider are dietary habits, work schedules, and environmental stressors.5-8 Over time, patients are often unaware of the additive deterioration of the enamel until spontaneous pain or sensitivity develops and/or significant portions of tooth shapes change and the patient is prompted to seek care. Typically, thinning enamel with no sensitivity is a telltale clinical presentation.

CASE REPORT

Diagnosis and Treatment Planning

An adult female patient came to our office with the following presentation for a consult for cosmetic treatment (Figure 3). Initial photographs were taken and put on an operatory monitor for the patient to best explain what changes she wanted to make to her smile. Her chief complaint: “I am embarrassed to smile and want my teeth to look natural.”

|

| Figure 3. Initial case presentation. |

A comprehensive examination was performed that included periodontal charting, a full-mouth radiographic series, and a panoramic radiograph (Panorex). Normal periodontal values were recorded, and no caries were found. A soft-tissue and cancer screening did not yield any findings. However, erosive facial lesions were evident on multiple teeth: maxillary teeth Nos. 3 to 14 and mandibular teeth Nos. 23 to 26. Also noteworthy was a general loss of all canine cusps and maxillary anterior incisal edge chipping and thinning. Further clinical evaluation revealed a deep bite, with the lingually inclined maxillary anterior teeth almost enclosing the mandibular anterior teeth. Her right maxillary lateral overlapped the adjacent canine. Bilateral canine protection of the anterior teeth was absent in lateral excursions. No clicking was found in her temporomandibular joints, and no parafunctional habits were noted. Her midline had shifted approximately 3.0 mm to the right. She presented with a Class II, Division 2 malocclusion.

|

| Figure 4. Invisalign (Align Technology) template. |

After much discussion, the patient revealed she had lived abroad (France) much of her adult life and, several years ago, began drinking hot water laced with fresh lemon juice every morning. This habit continued for at least 3 years, by her recollection. She discontinued this habit after her front teeth began to discolor and became more sensitive to air and water. She also could not recall the use of any toothpaste brand, fluoride rinse, or other preventive measures.

The patient’s malocclusion was of primary concern. Dental erosion was clearly evident and exacerbated the anterior malocclusion. If the occlusion was not corrected, more exposed dentin would be lost, and restorative recovery would be much more difficult.

These findings were shared with the patient. Clear explanations of treatment choices, a timeline, and aesthetic expectations were given to her. Also, preventive maintenance was emphasized. We used patient photographs, drawings, and models to ensure equal expectations between clinician and patient were met. The patient agreed to an orthodontic consultation to start treatment.

Pre-restorative Orthodontic Phase

An initial orthodontic discovery was completed with photographs and impressions (Figure 4). The treatment plan included a series of clear aligner therapy (Invisalign [Align Technology]) for 14 months. During this phase, the patient was very compliant, wearing her aligners and diligently changing them every 10 to 12 days. Because the aligner plastic would be covering the teeth for 22 hours per day, a preventive maintenance roadmap was created and presented by a hygienist. This regimen included daily application of RECALDENT (GC America), which is contained in MI Paste Plus (GC America). RECALDENT is a milk-derived protein (CPP-ACP) that offers a bio-available release of calcium and phosphate into the tooth surfaces (Figure 5). The goal was to lessen any potential sensitivity and provide oral buffering. The patient was advised to brush her teeth before bedtime in a traditional manner. She was advised to place a pea-sized amount of MI Paste Plus on her tongue and then use that to coat all the surfaces of her teeth and was instructed not to rinse. This coating was to remain undisturbed for 20 minutes. After that time, she was allowed to insert her aligner for bedtime wear.

|

| Figure 5. The patient applied MI Paste Plus (GC America). |

After 14 months, the final arch alignment and orthodontic result was achieved. Note the regained anterior space and posterior support (Figure 6). Both arches were maintained with an Essix ACE clear aligner for 6 months before restorative treatment would commence.

Restorative Phase 1

The restorative phase was ready to begin after 6 months of retention. Due to the loss of canine anatomy and guidance, the mandibular anterior teeth were initially restored with direct composites.

|

| Figure 6. The final alignment, post-orthodontic treatment. |

Teeth Nos. 22 to 27 were isolated, pumiced, rinsed, and shade matched. Two-ml bevels were placed on the enamel framework edges to enhance adhesion. Each tooth was interproximally isolated with a clear matrix. A selective-etch method was done using a phosphoric acid etchant that was applied to the enamel for 15 seconds, then rinsed thoroughly with water for 5 to 10 seconds, and then excess water was removed while allowing for a moist surface to remain. A fresh drop of universal bonding agent (Prime&Bond elect [Dentsply Sirona]) was scrubbed into the enamel and dentin surfaces equally for 20 seconds, followed by syringing a clean air stream for 5 seconds to thin the bonding agent. Each surface was light cured for 20 seconds. A universal composite (TPH Spectra ST [Dentsply Sirona]) in shade BW (bleach white) was applied and sculpted to restore the missing tooth surfaces, then appropriately light cured (SmartLite Focus [Dentsply Sirona]). The patient’s restored occlusion would guide the height of the canines. Each restoration was finished, occlusion verified, and then polished using discs and cups (Enhance [Dentsply Sirona]) to achieve a nice luster. The patient was very pleased with the mandibular restorative phase (Figure 7).

A mandibular impression was taken to create a new retention aligner. The patient was scheduled to return in 2 months for her final restorative phase.

Restorative Phase 2

The final phase of the treatment plan called for the 6 maxillary anterior teeth to be protected and restored with pressed all-ceramic veneers (IPS e.max Press [Ivoclar Vivadent]). Per the patient, care was taken to restore the original shade and shape of her teeth with respect to the missing incisal line angles and edges. This was an opportunity to create a chairside mock-up for the patient to best visualize and approve her new aesthetic look. This “new look” was used to create a template for the upcoming transitional restorations.

|

|

| Figure 7. The completed mandibular restorative phase. |

|

|

| Figure 8. Maxillary veneer transitionals. | Figure 9. The completed maxillary veneers. |

The patient was given a local anesthetic, and, using a minimally invasive approach as much as possible, veneer preparations were created. Then impressions and a bite registration were taken, and provisional restorations were fabricated (Figure 8).

After 2 weeks, the patient returned for her insertion appointment. Again, local anesthetic was given, and the temporaries were removed. The preparations were pumiced and rinsed, and the veneers were tried in using a translucent try-in paste (Calibra Veneer Esthetic Resin Cement [Dentsply Sirona]) to confirm the fit. At this point, the aesthetics were also evaluated and approved by the doctor and the patient. Each veneer was thoroughly rinsed and dried. Next, the intaglio surface of each veneer was coated with universal primer (Silane coupling agent [Dentsply Sirona]) and allowed to air dry. A thin coat of bonding agent (Prime&Bond elect) was applied and then air dried for 5 seconds. Each veneer was set aside and covered to prevent any premature adhesive curing from the ambient operatory lights. A total-etch method was used, acid etchant was applied on each preparation for 15 seconds and then rinsed with water for 10 seconds, and then the excess water was removed to the extent that the tooth remained moist. The bonding agent was then scrubbed into each preparation for 20 seconds, and then each preparation was air-thinned for 5 seconds to prevent any pooling. Each prep was then light cured for 10 seconds, beginning with the maxillary centrals. During this time, an aesthetic veneer cement (Calibra Veneer Esthetic Resin Cement, Light shade) was loaded into the restorations. As the restorations were seated, care was taken to ensure proper placement. The gingival portion was briefly light cured for no more than 10 seconds, and excess cement was carefully removed. A final, 20-second light curing of all surfaces was completed. Margins were finished using a fine, flame-shaped diamond and then lightly polished, as needed, using a composite polishing point. Finally, all the restorations were flossed, and the occlusion was reverified (Figure 9).

Postoperative Care

The patient’s anterior tooth enamel that was once threatened by erosion on the buccal surfaces was now fully protected with bonded all-ceramics. A final clear aligner retainer was delivered that the patient would continue to wear for 6 months, then alternate nightwear thereafter. She was advised to follow the home care instructions given to her for the rest of her life.

CLOSING COMMENTS

I had never before encountered dental erosion to this extent in my practice. This condition presented as a significant, multifactorial treatment challenge. Through the work required to treat this patient, I have learned that dentists and hygienists need to create strategies for a cohesive message when diagnosing and staging a case of this magnitude. Our dual role is to not only restore patients’ oral health but also to encourage and support them along the transformation process.

Acknowledgments:

The author would like to thank Dan Becker at Becker Dental Lab in Herculaneum, Mo, for the beautiful ceramic work.

References

- American Dental Association. Oral health topics. Dental erosion. https://www.ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/dental-erosion. Accessed February 21, 2019.

- Scheutzel P. Etiology of dental erosion—intrinsic factors. Eur J Oral Sci. 1996;104(2 pt 2):178-190.

- Twetman S. The evidence base for professional and self-care prevention—caries, erosion and sensitivity. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15(suppl 1):S4.

- Imfeld T. Dental erosion. Definition, classification and links. Eur J Oral Sci. 1996;104(2 pt 2):151-155.

- Shlossman M, Montana M. Preventing damage to oral hard and soft tissues. In: Spolarich AE, Panagakos FS, eds. Prevention Across the Lifespan: A Review of Evidence-Based Interventions for Common Oral Conditions. Charlotte, NC: Professional Audience Communications; 2017:97-120.

- Zero DT. Etiology of dental erosion—extrinsic factors. Eur J Oral Sci. 1996;104(2 pt 2):162-177.

- Huysmans MC, Chew HP, Ellwood RP. Clinical studies of dental erosion and erosive wear. Caries Res. 2011;45(suppl 1):60-68.

- Meurman JH, ten Cate JM. Pathogenesis and modifying factors of dental erosion. Eur J Oral Sci. 1996;104(2 pt 2):199-206.

Dr. Trost received her dental degree from the Southern Illinois University School of Dental Medicine. She maintains a private practice in the Greater St. Louis area. Dr. Trost offers postgraduate courses to dentists and their team members that draw from her extensive private practice experience and focus on restorative dentistry, digital technology, dental materials, orthodontics, business management, and patient communication. She is an author, clinical evaluator, and editorial board member and is listed as one of Dentistry Today’s Leaders in Continuing Education. She can be reached at loritrost.com or via email at trost@htc.net.

Disclosure: Dr. Trost reports no disclosures.

Related Articles

Shedding the Right Light on Aesthetics

Dentistry Named Fourth Best Job by US News & World Report

Conservative Interdisciplinary Dentistry: A Digital Approach to an Analog Problem