You present an extensive treatment plan involving crowns/veneers or even full-mouth restorations. Your patient listens intensively and seems to agree with your treatment plan. However, a few days later, your patient asks your office to send his or her records to another dental office. In reality, we have all had this happen. This article will go into several techniques that have proven successful for the authors over the years to improve your patients’ understanding of their clinical conditions and increase the predictability of your case acceptance.

RULE 1: DO NOT SCARE YOUR PATIENT

Chances are your patient has been under the care of other dentists who may have been telling the patient all is well or, in many cases, communicating very little to the patient. This is not the situation with patients who come to you knowing they have a major problem and think you are the best to solve it.

|

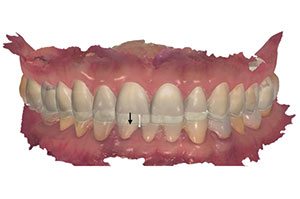

| Figure 1. This patient wanted a more-proportionate-looking smile but had more space on one side than the other. There was also a loss of interdental tissue between the centrals and laterals and incisal wear on the central incisors. |

|

|

| Figure 2. The right lateral view shows exposed, dark crown margins; dissimilar tooth shades; and lower incisor tooth wear. | Figure 3. The left lateral was considerably out of proportion and contained stained composite-resin-bonded restorations, in addition to wear at the posterior cervical margins. |

So first, identify the problem. Not like one of the authors who recently looked at a new patient’s smile and said “I see the problems” since there were many. The patient presented with tooth wear; spaces that were much wider on one side than the other; discolored and stained teeth; overbuilt bonding; and a loss of interdental space, especially between the 2 central incisors (Figures 1 to 3). Comprehensive treatment planning was begun with the dental assistant making extensive notes. Diagnostic models were made and articulated, plus a wax-up was designed of what her smile would look like. In 2 weeks, the treatment plan was presented to the patient.1,2 After listening patiently, she said, “Doctor, I don’t care about the larger teeth, the spaces, or even the gum loss. I just want these 2 side teeth fixed.” (She pointed to her maxillary lateral incisors.)

RULE 2: NEVER ASSUME

When it comes to treatment acceptance, assumption can be the first step to failure! Ask what the patient’s concerns are instead of assuming. Aesthetic dentistry is not an urgent need; in fact, it isn’t really a need. It is something people learn to want. People have to be in the right place emotionally to want something. In fact, the root word “aesthetic” means “creating a pleasing emotion.” Thus, it is with great care that one must gently “ask” patients if something about their smile concerns them rather than tell them something is unaesthetic. It has been said millions of times: “A picture is worth a thousand words.” In a “wants-based” practice (or any other synonym for an aesthetics-based practice), photography is the most powerful tool to motivate people to treatment. We feel you cannot create a wants-based practice with high case acceptance without routinely taking high-quality preoperative images of your patients to lead them to the appropriate treatment decisions. Furthermore, you also need high-quality postoperative images to demonstrate to future patients the types of treatments that might be appropriate for them.3

RULE 3: DON’T RUSH THE NEW PATIENT

You should know from your receptionist, patient coordinator, or another person who first interviews the new patient both the extent of the problem and what the patient expects from the appointment. Continue to extract this information when the patient presents at the office and is seated by the dental assistant (if he or she is the first to see the patient). Although this information will certainly help you narrow the patient’s personal history, you must spend the time necessary to be certain on what the patient expects from your consultation and diagnosis.4

|

|

| Figure 4. A colored intraoral scan (IOS) using TRIOS 3 (3Shape). | Figure 5. Using 3Shape’s dental designer, you are able to digitally align the IOS to the patient photo to help plan the case correctly in the horizontal plane and avoid caning to one side. |

|

| Figure 6. A 3-D digital diagnostic wax-up (DDW) (3D Systems) model was 3-D printed (JUELL 3D-2 [Park Dental Research]). |

When the Patient Gives You License

Obviously, the best scenario would be the patient who says, “Doctor, I know I have a lot of problems, and I am ready to fix them.” That statement should be followed by “Then please tell me what you would like to see?” Another good ice-breaker is “If I give you a magic wand that you could wave across your smile, what would you like to have your smile look like?”

This type of patient conversation should end in one of these 3 ways:

1. The patient gives you license to do a thorough smile analysis and an ideal treatment plan. This option also depends on if the patient has a good idea of your fees.

2. The patient states, “I wish I could afford a new smile, but I know my insurance will not cover it.” This answer gives you the chance to reply, “There may be compromises where we can make a real difference in your smile.”

3. The patient finally discloses, “Nothing bothers me, but…”

Regardless of which option you receive, you should be off to a good start in not only not scaring the patient but also in not giving the impression that you are “selling” treatment he or she may not feel is necessary. This way, you are better seen as a health professional who not only understands a patient’s problems but also will come up with answers to truly help your pa

tient.

Good plastic surgeons will usually give their new patients a mirror and say, “Please tell me what you don’t like about yourself.” Dr. Goldstein does this, especially with new patients, when he sees a potential facial component to changing a smile. It allows the patient to voice potential plans for a face-lift, filler injections, or even lip enhancements. He recalls a celebrity patient who, right in the middle of her extensive treatment and without any warning beforehand, went into a hospital to have her lip enhanced. This affected the shape and length of the maxillary anteriors due to the extreme shadows the upper lip created on her front teeth as a result of the increased lip thickness.

When a patient does tell you he or she plans facial plastic surgery, you need to warn the patient to do the dental makeover first so that you will not have to traumatize or stretch the lips when preparing teeth or taking impressions later.5

|

| Figure 7. An aesthetic prototype, using the impression made from the DDW 3-D printed model. |

Letting Patients See Their Problems

We always recommend performing complete intraoral and extraoral photographs and periodontal and radiographic exams to make sure you find problems that the patient’s previous dentist may have overlooked. Many of the findings may turn out to be warnings (such as wear facets indicating bruxism or clenching, thus resulting in the suggestion of a night guard or other treatment). We also suggest the complete intraoral camera exam to discover hidden microcracks or caries. If the patient has undiagnosed pain or ongoing discomfort, it may also be wise to obtain a CBCT scan, especially if you plan extensive restorations.

RULE 4: DIGITAL SMILE DESIGN

With the advent of digital imaging and programs like Adobe Photoshop for digital image manipulation or programs specifically designed for dental applications (eg, DSD [digital smile design]), it is now a simple process to show a patient a “digital smile enhancement” prior to attempting any actual treatment. The authors find it a very powerful motivational tool, especially in those patients who “don’t see” the aesthetic or dental issues that you do. The simple question you can ask the patient is “Do you mind if I take a couple of images of your face and teeth so I can show you digitally some of the new materials and techniques that can be done to enhance smiles?” They will always ask (especially if they did not come in seeking aesthetic dentistry) “Is there a charge for this?” With digital technology, this is a 10- to 20-minute process that can be mostly staff-mediated; thus, early in your practice career, I would strongly consider giving this time away. Consider this like a test drive of a car or trying on clothes: It takes very little time but can be quite motivating to cause the consumer to buy.6,7

Moving From Digital/Verbal Communication to an Analog Trial Smile

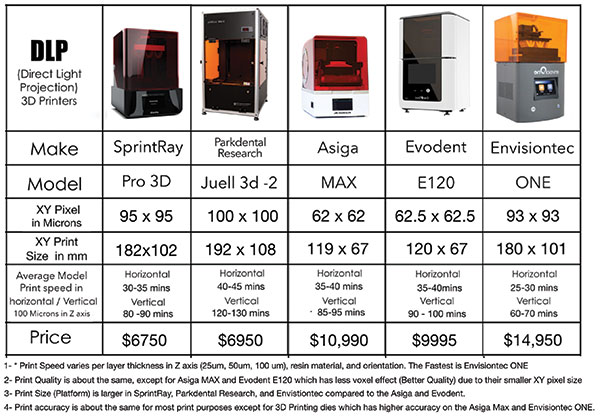

One of the most valuable techniques to finally convince a patient to move forward with the proposed treatment is what has been traditionally termed a “mockup.” Other terms have been used, such as “trial smile,” and the authors coined the term “aesthetic prototype,” as the word “prototype” better describes what is being done. “Prototype” literally means “working functional model,” and the goal is to make it aesthetic. Two functions can be accomplished with an asthetic prototype: (1) aesthetics can be verified and altered before treatment is started, and (2) it is possible to verify if the patient will functionally adapt to the altered form proposed. Today, in the digital world, it is possible to collect all the needed data for producing a 3-D digital diagnostic wax-up (DDW) in one-tenth the time it takes to do the same diagnostic wax-up conventionally.8 You can scan the teeth using an intraoral scanner, followed by taking 2 full-face photos (repose and smile). Using computer-aided design (CAD) software, the intraoral scan is aligned over the full-face smile photo using matching reference points (Figure 4). Once you have the intraoral scan aligned correctly, you can have the DDW (3D Systems) completed (Figure 5) according to your aesthetic analysis and functional planning using the digital articulator. The DDW is combined digitally with the patient pre-op intraoral scan and sent to be 3-D printed (Figure 6). You can now make an impression of the printed DDW model, which you can then fill with bis-acryl for the aesthetic prototype (Figure 7). At this point, the patient is able to see a prototype of the final result before any irreversible dental work is done. You can now prep through the prototype to preserve tooth structure, and you are also able to use the DDW impression to make the temporaries. There is a cost to this, but it is a lot less than the conventional way of impressions and full-mouth, conventional wax-ups. The digital approach has a much faster turnaround time and can be just as or potentially more accurate compared to the conventional way. Three-dimensional DDWs and 3-D printing are the future of prototyping. Table 1 shows a list of different 3-D printers that would work for 3-D printing prototype 3-D DDWs.

|

| 1 — Print speed varies per layer thickness in axis (25 µm, 50 µm, 100 µm), resin material, and orientation. The fastest is EnvisionTEC ONE. 2 — Print quality is about the same, except for Asiga MAX and Evodent E120, which have less voxel effect (better quality) due to their smaller XY pixel sizes. 3 — Print size (platform) is larger in SprintRay, Park Dental Research, and EnvistionTEC models compared to the Asiga and Evodent models. 4 — Print accuracy is about the same for most print purposes, except for 3-D printing dies, which is more accurate on the Asiga Max and Evisiontec ONE cDLM. |

Whether or not the aesthetic prototype is used as a final “motivational” technique to get the patient to say yes to the treatment or used to verify the final aesthetic and functional design, it is strongly recommended by the authors to use one of the variations of this technique.

CLOSING COMMENTS

We are all taught how to use the wonderful materials and techniques that are available to us today. It is just as important to the success of our practice that we learn the interpersonal skills and techniques that will maximize our patients wanting the highest quality dentistry we have the ability to deliver. We must understand that we and each of our patients are in different periods of our lives and currently living through events that will affect our decisions to do anything. When patients are in the right frame of mind, have the right personal circumstances, and are properly educated and motivated, they will ultimately make the right decisions for themselves. It is our and our teams’ challenge to help them with that—and you thought you were just going to be a dentist.

References

- Goldstein RE. Patient education reaches new heights. Contemporary Esthetics and Restorative Practice. 2004;8:14-17.

- Goldstein RE. Communicating esthetics. N Y State Dent J. 1985;51:477-479.

- Goldstein RE. Digital dental photography now? Contemporary Esthetics and Restorative Practice. 2005;9:12-15.

- Goldstein RE. Esthetics in Dentistry: Principles, Communications, Treatment

Methods. 2nd ed. Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: BC Decker; 1998. - Goldstein RE, Chu SJ, Lee EA, et al, eds. Esthetic treatment planning. In: Ronald E. Goldstein’s Esthetics in Dentistry. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2018.

- McLaren EA, Chang YY. Photography and Photoshop: Simple tools and rules for effective and accurate communication. Inside Dentistry. 2006;2:97-101.

- McLaren EA, Figueira J, Goldstein RE. A technique using calibrated photography and Photoshop for accurate shade analysis and communication. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2017;38:106-113.

- McLaren EA. Bonded functional esthetic prototype: an alternative pre-treatment mock-up technique and cost-effective medium-term esthetic solution. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2013;34:596-607.

Dr. Goldstein is currently a clinical professor of restorative science at the Dental College of Georgia at Augusta University, an adjunct clinical professor of prosthodontics at the Boston University (BU) Henry M. Goldman School of Dental Medicine (GSDM), and an adjunct professor of restorative dentistry at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. He is co-founder and past president of the American Academy of Esthetic Dentistry and past president of the International Federation of Esthetic Dentistry. In 2008, Dr. Goldstein founded the Tomorrow’s Smiles program under the National Children’s Oral Health Foundation to help deserving adolescents receive cosmetic dental treatment and enjoy the benefits of a healthy smile. He is a contributor to 11 published texts and author of the 2-volume text Esthetics in Dentistry, Third Edition (Wiley, 2018). His best-selling consumer book, Change Your Smile, now in its fourth edition, has had more than 2 million readers and has been translated into 12 languages. He is currently on the editorial advisory boards of Dentistry Today and Inside Dentistry. He can be reached via email at esthetics@mindspring.com.

Dr. McLaren received his DDS degree from the University of the Pacific Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry and a specialty certificate in prosthodontics from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), School of Dentistry. He is a retired professor at the UCLA School of Dentistry, founder and the first director of postgraduate aesthetics at the UCLA Center for Esthetic Dentistry, and founder and the first director of the UCLA/Los Angeles City College Master Ceramist Program at the UCLA School of Dentistry. He has presented numerous lectures, hands-on clinics, and postgraduate courses on ceramics and aesthetics across the nation and internationally. He can be reached at me@thinkgreen.me.

Dr. Tadros earned his DMD degree from Georgia Regents University. He pursued a 3-year residency program that specializes in prosthodontics at the Dental College of Georgia at Augusta University. He is in private practice in Atlanta and is a prosthodontist and director of digital dentistry at Goldstein, Garber, and Salama. He is founder and director of the 365 Digital Dentistry Mastership Program. He can be reached at markotadrosdmd@gmail.com.

Disclosure: The authors report no disclosures.

Related Articles

Effective Measurements for Predictable Aesthetic Success

Evolving Dental Technologies: A New Level of Patient Care and Communication