The popular media often portrays people with eating disorders as vain young women obsessed with their appearance. But that’s a dangerous stereotype, as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa affect males and females across every demographic, often as the result of complicated psychological causes. Yet dentists can play a significant role in helping those who suffer from them begin their road to recovery by identifying their symptoms and initiating communication.

“If somebody is looking like they’re losing a lot of weight, you may be able to make ways to have a conversation because you’re going to be seeing them twice a year in theory, and so maybe you can see changes more clearly than somebody who is seeing them every day,” said Martha Levine, MD, director of the Intensive Outpatient and Partial Hospitalization Eating Disorder Programs at the Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center.

The Physical Signs

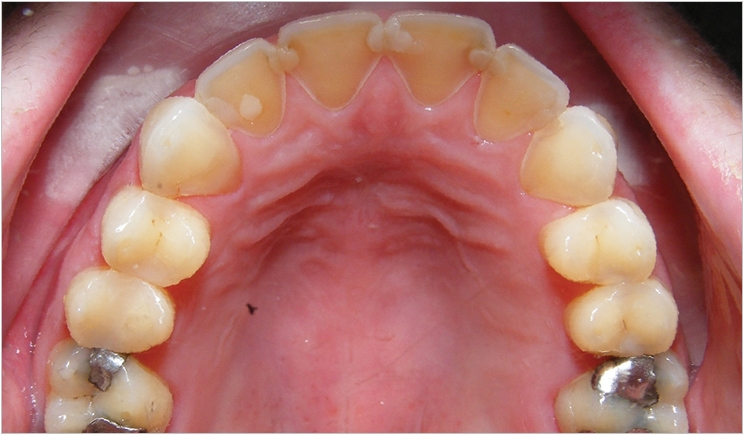

In addition to the differences in weight, patients with eating disorders present very specific physical symptoms in the oral cavity that dentists should be able to note. For example, there may be signs of physical harm to the soft palate such as bruising as these patients with bulimia nervosa use their fingers or other objects to induce vomiting, Levine said. Plus, these patients will have worn enamel, particularly on the backs of their teeth, due to the vomiting.

The continued exposure to acid also may lead to dental caries or an increased susceptibility to cavity development, a chronic sore throat and hoarse voice, painful or bleeding gums, difficulty or pain in swallowing, a dry mouth, decreased saliva production, abnormal jaw alignment, broken or cracked teeth, chewing difficulties, reversal of previous dental work, and damage to the esophagus, according to Eating Disorder Hope, an organization that serves these patients.

“The other thing we see a lot is enlarged salivary glands because they get stimulated with all of this activity. So a lot of our patients have almost a chipmunk look, with very large parotid salivary glands,” said Levine. “Sometimes, and dentists wouldn’t necessarily be noting this, but there’s a sign called the Russell’s sign that shows a lot of callousing, usually on the back of the index finger, from people going over their teeth and getting rubbed and calloused.”

Patients with anorexia nervosa display similar symptoms, as their limited diet leads to nutritional deficiencies. Insufficient calcium and vitamin D may yield tooth decay and gum disease, while insufficient iron can foster the development of sores in the oral cavity, reports the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA), an advocacy and support group. Also, insufficient vitamin B3 or niacin can produce bad breath and canker sores. Dry mouth and swollen and bleeding gums are possible as well.

Additionally, NEDA reports, the temporomandibular joint may develop degenerative arthritis. Pain in the joint area may follow, along with chronic headaches and problems chewing and opening and closing the mouth. Levine notes that osteoporosis is possible as well due to poor overall bone health, with a decrease in bone mass in the jaw area. And, there are signs beyond the oral cavity that dentists may be able to spot too.

“When individuals struggling with anorexia are very thin, oftentimes they have just an overall unhealthy thinning of their hair,” said Levine. “Sometimes they develop very fine hairs, called lanugo, on their arms because the body is trying to keep itself warm as they start to lose a lot of weight.”

The Demographics and Causes

According to NEDA, 20 million women and 10 million men in the United States suffer from a clinically significant eating disorder at some point in their life, including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, or other specified feeding or eating disorder. Eating Disorder Hope reports that 1.0% to 4.2% of women will experience anorexia nervosa and up to 4% of women will have bulimia nervosa in their lifetime.

“By and large, we see a lot of women,” said Levine. “But there are times that men will not want to admit that there’s an issue because it’s seen very much as a women’s disease. While our sense is that it really is in large part about women, you really need to be aware of it in any gender. Sometimes we are seeing challenges within the LGBT population.”

For example, Levine said, there is an elevated risk in those who are trying to appear attractive to males, including homosexual males and heterosexual women. Transgender individuals may suffer from an eating disorder as they try to control their body and shape it towards the gender that they identify with. And overall, patients with eating disorders tend to develop them during times of transition or times of stress.

“Women, if they are going through puberty, especially early puberty, can see an increase in anorexia for a number of reasons. They may get a lot of bullying, or negative comments from family or friends, because they’re now looking different. Those comments can trigger a lot of the eating disorder thoughts and focus on shape,” Levine said.

These adolescents may begin to be the subject of sexualized comments but they may lack the emotional ability to deal with these expectations, Levine said, particularly if they are young. The eating disorder, then, is driven by a need to be smaller and return to a pre-pubertal shape. Similarly, child abuse and sexual assault may affect these patients’ views of themselves and prompt a need for control, manifesting in the eating disorder.

“The other time we sometimes see an increase is when women go off to college, and it’s a big change with less support. For a lot of individuals, this change is very difficult. There’s suddenly a wide variety of food and food expectations, so you can often see a spike in eating disorders at that time,” Levine said.

Middle-aged patients may experience an eating disorder during a divorce, which will affect how they view themselves, Levine added. Or, patients who are trying to improve their health may go too far and “can’t get off of the dieting treadmill,” Levine said. And while popular culture may have an effect, the home environment may matter more.

“Families should look around to see what messages we are sending. If we have a lot of fashion magazines, or if moms are worried about dieting or their size, that’s going to get passed on to their daughters. But if we can be more concerned about being healthy, without worrying about a certain look all the time, that could be more protective,” Levine said.

The Communication

Dentists who believe a patient may have an eating disorder should initiate a conversation about their suspicions, but these discussions must be handled very discretely. Patients with eating disorders strive to keep their condition a secret, and bringing it up may lead to defensiveness and denials. The patient also might not return for further treatment, eliminating the possibility for help. And if the discussion is perceived as an accusation, the negative feelings the patient may have may further drive the needs that compel the disorder in the first place.

First, dentists should make sure they have a private area such as their office or an individual operatory where they can close the door before they begin such a conversation, Levine said. Patients will not want to talk about their struggles if they can be overheard by other patients or dental personnel. Next, dentists should realize that it’s not going to be a quick chat.

“Make sure you have time to talk about it. It’s not something that you’re going to want to dash off and say, ‘Hey, I think you might be having some struggles with your eating. Here’s a card of an eating disorder clinic.’ Because they’re not going to follow through with that. So make sure you have that kind of time and a good space to really have a conversation,” said Levine.

Once the conversation begins, it should be open-minded and open-ended, without judgment, blaming, or shaming. The discussion shouldn’t necessarily begin with the eating disorder, either. Dentists should approach it indirectly and see if the patient is willing to bring it up.

“Just say, ‘I’m really worried with what I’m seeing with your teeth. And there can be a lot of different reasons for it. I’m noticing that there’s a lot of damage. Do you have any thoughts about what might be causing it?’ They might not open up at that point. You can continue with, ‘Some of the things that we’ve seen that cause problems like this are chronic vomiting or stomach acid. Are you having any problems like that?’” Levine said.

“Open-ended questions are a great way to get patients to talk with us, rather than going down a checklist, because people will tell us as much as they think we want to hear sometimes. If they think all we want to hear is ‘Yes, I have a problem’ or ‘No, I don’t have a problem,’ then that’s all we’re going to get, and we probably won’t really find out what’s going on. But if we really say ‘I’m interested in helping you. Can you tell me what might be going on?’ they will often provide much more information and really feel somebody is interested in helping them.”

If the patient is willing to discuss the disorder, then dentists should be prepared to provide referrals to specialists who may be able to help. Dentists also should ask if they can discuss the issue with the patient’s primary care provider. But some patients will rebuff the topic and even deny there is a problem in the first place. It may take multiple visits before the patient is willing to open up, if it happens at all.

“Put it in your chart or in your notes that you’ve had this conversation, and try again at the next appointment, especially if things are getting worse in any way,” Levine said. “Again, don’t be judgmental or shame the person. Just say, ‘I know we’ve talked about this before, but you’re still having a lot of these issues here, and I’m really worried about it. Let’s go through it again and really think about if there is something going on.’ That would be the main way I would say to approach it.”

Some of these patients may be adolescents, complicating matters in terms of confidentiality and parental permissions. Regulations vary and must be followed, though Levine notes that in adolescent medicine, she and her colleagues often start their conversations with the adolescents first and later bring in their parents. In some areas, patients as young as 14 or 16 years old may be able to make their own decisions about psychiatric treatment, she said.

“We never want to violate that, but we also want to make sure that we bring in the parents,” Levine said. “A lot of times it could be approached with the adolescent, and then just say, ‘You know, I think this is an important conversation to have. Let’s bring your mom or dad in to talk about what’s going on.’ But you’re going to have a lot more buy-in from the adolescent if you start with them first and then say, ‘This may be a tough conversation to have, so let’s bring your mom and dad in, and we can all do this together and help provide some support.’”

Levine also acknowledges that age and gender gaps may be difficult to overcome in these discussions. Young women, for example, may not be comfortable opening up to older men no matter how compassionate they are in bringing up their concerns. In those situations, younger female members of the staff may be better suited for initiating the communication, bringing others into the conversation as necessary.

“The most important thing is to have a basic understanding and approach the conversation in a calm way and not be judgmental, because a lot of these patients have already faced a lot of judgment from other people, including their families, who say, ‘I don’t understand it. Just eat,’ or ‘Just stop throwing up.’” Levine said. “They get a lot of criticism at times from other places. So if they feel like somebody is really worried about them and is willing to talk and is not going to judge them, they will be much more willing to open up about it.”

For More Information

There are many resources available for dental professionals who want to learn more. For example, Levine’s chapter “Communication Challenges Within Eating Disorders: What People Say and What Individuals Hear” from Eating Disorders—A Paradigm of the Biopsychosocial Model of Illness is available online. Levine also recommends “Communicating Effectively With Patients Suspected of Having Bulimia Nervosa” by Burkhart et al from the August 2005 issue of the Journal of the American Dental Association.

Related Articles

Acid Erosion Awareness Campaign Gets Underway