Humans can’t regrow their adult teeth. But every 35 to 45 days, mice wear down and completely renew their incisors, which makes them especially useful for studying how adult stem cells regenerate tissue. And the stem cells in mouse incisors are more abundant, active, and dynamic than previously thought, according to the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research, challenging previous views of how the tooth system functions.

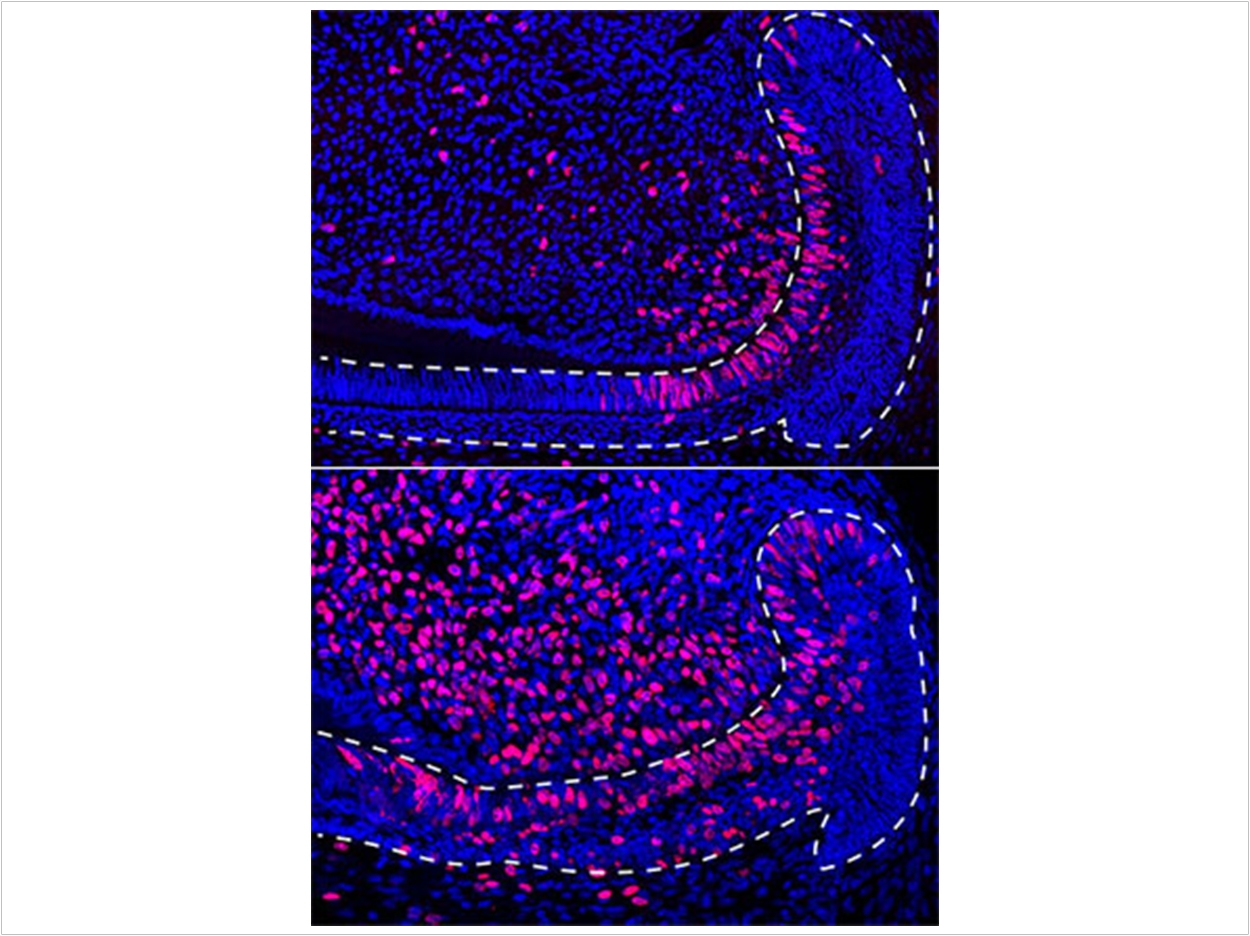

A team of researchers from multiple institutions carefully examined the individual cells in the epithelium, a layer of the mouse incisor where stem cells give rise to enamel. Using single-cell RNA sequencing, the team identified each cell’s unique genetic signature. Comparing gene profiles and analyzing cell changes then helped the team determine how different cells in the epithelium behave.

Also, the team mapped the cells to specific areas in the epithelium and showed how the dental epithelium recovers from injury. Previously, researchers believed the stem cells in the epithelium weren’t especially active and resided in its outer area. They also believed this outer region produced ameloblasts, which are the cells that deposit enamel, and cells thought to provide physical and nutrient support to ameloblasts.

In the lab, the researchers found the stem cell in the epithelium are actively dividing even under steady state conditions and that they are located in the inner area of the epithelium, not the outer area. Contrary to expectations, the researchers also demonstrated that these stem cells give rise to the ameloblasts and the cells of a section of non-ameloblast epithelium that supports the ameloblasts.

To determine how the epithelium handles injury, the team damaged the tissue with a cancer drug that targets actively dividing cells. Instead of producing a cell type specific for injury repair, the injured epithelium responds unexpectedly. Cells in the inner region of the epithelium become more abundant and active, and one population of support cells directly converted into ameloblasts that could then regenerate the damaged tissue.

“Although there is not a direct link between ever-growing rodent teeth and human teeth, we believe that by understanding the fundamental mechanisms by which nature normally renews teeth across different types of animals, we will be able to lay a foundation for human tooth regeneration,” said Ophir Klein, MD, PhD, a professor of orofacial sciences, human genetics, and pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco.

The study, “A Large Pool of Actively Cycling Progenitors Orchestrates Self-Renewal and Injury Repair of an Ectodermal Appendage,” was published by Nature Cell Biology.

Related Articles

Gene Activates Stem Cells and Could Regenerate Tissue

Stem Cells Used to Regenerate Pulp and Dentin

Pericytes Identified as Source of Stem Cell Precursors in Teeth