When most people think of the teeth on prehistoric creatures, they imagine the Smilodon, better known as the saber-toothed tiger. But among dinosaurs, theropods are well-known for blade-like teeth with serrated cutting edges used for biting and ripping their prey.

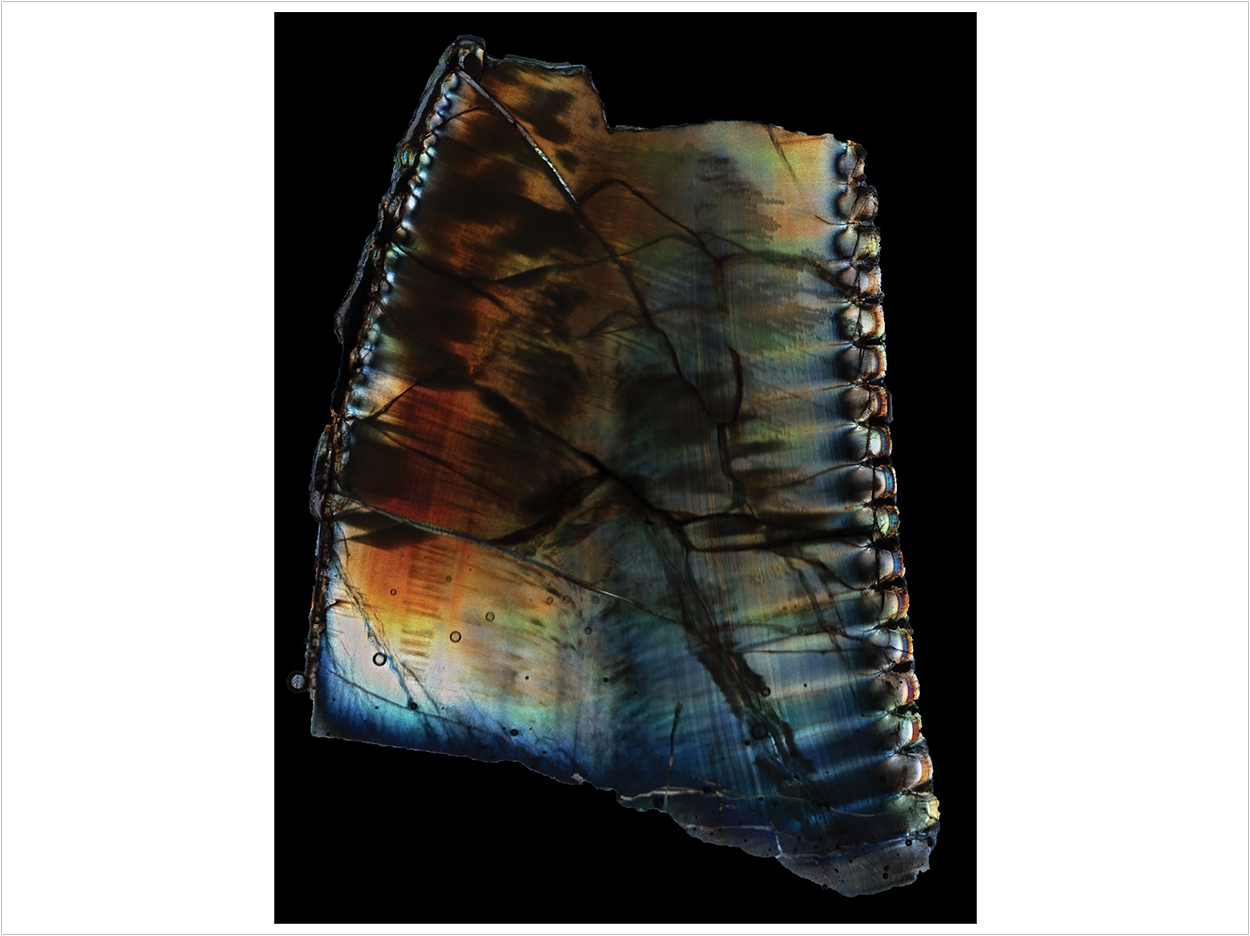

Until recently, the complex arrangement of tissues that gave rise to these teeth was considered unique to these meat-eating dinosaurs. An international team of researchers, however, has examined the thin fossil slices of teeth from gorgonopsians and discovered similar complex arrangements of tissues that made the steak-knife-like serrations in theropods.

Gorgonopsians are a group of synapsids from the middle-late Permian era, between 270 million and 252 million years ago. Like other synapsids, these animals are considered to be the forerunners of mammals and fall within the lineage that eventually gave rise to mammals.

“Paleontologists can tell a lot about the diets of extinct animals by looking at the shapes of their teeth, and gorgonopsians had some impressive teeth to study,” said Dr. Aaron LeBlanc, the Marie Curie Postdoctoral Fellow at the Faculty of Dentistry, Oral & Craniofacial Sciences at King’s College London.

“These animals were the apex predators of their day and are characterized by their sabre-like canines that could extend up to 13 cm long,” said Dr. Megan Whitney, postdoctoral researcher with the Department of Organismic & Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University.

Previous studies of theropod dinosaurs uncovered a complex arrangement of tissues made of both enamel and dentin that formed the serrations on their teeth. This complex arrangement was considered unique to theropod dinosaurs, but no one had ever made a thin section of a gorgonopsian tooth before to examine the serrations.

The researchers then combined their expertise in paleohistology, or the study of the microstructure of fossilized skeletal tissues, and examined thin sections of fossils from three synapsids from three different time periods to test a theory of the structure of the serrations in this group.

“We were surprised to find theropod-like serrations in gorgonopsians,” said Whitney. “We wanted to see how other carnivorous synapsids had made their serrations, so we looked at an older synapsid [Dimetrodon] and a younger, mammalian synapsid [Smilodon].”

Gorgonopsians, Dimetrodon, and Smilodon are all synapsids and, like theropods, were apex predators of their day with serrated, knife-like teeth (ie, ziphodonty). Dimetrodon is one of the earliest synapsids from the Cisuralian period around 295 million to 272 million years ago. It is often mistakenly described as a dinosaur. Smilodon lived in the Americas during the Pleistocene 2.5 million to around 10,000 years ago.

“All of these animals fall along the mammal line, which is divergent from the reptile line with dinosaurs,” said LeBlanc. “In fact, these three animals are more closely related to humans than to dinosaurs.”

The thin sections revealed that the gorgonopsian serrations are composed of tightly packed denticles made of both enamel and dentin, the same complex arrangement of tissues that had previously been attributed to theropod dinosaurs and considered unique to them.

“What’s surprising is that the type of serrations in gorgonopsians are more like those of the meat-eating dinosaurs from the Mesozoic era,” said LeBlanc. “It means that this unique type of cutting tooth evolved first in the lineage leading to mammals, only to later evolve independently in dinosaurs.”

“The fact that we only see this type of serration evolve in meat-eating animals is significant,” said coauthor Dr. Kristin Brink, assistant professor of paleontology in the Department of Geological Sciences at the University Manitoba.

“The tiny microstructures hidden inside the teeth offer a significant advantage to the tooth, strengthening the serrations and helping them last longer in the mouth, which in turn helps the animal eat efficiently,” Brink said.

Though gorgonopsians share this trait with theropod dinosaurs, they actually share more characteristics with other synapsids like Dimetrodon and human beings.

“These animals converged on a similar tooth serration morphology because of the functional benefits, not because they’re close relatives to one another,” said Whitney.

“In this case, it probably has something to do with the fact that animals were really putting a lot of wear and tear on their teeth. And so independently they’ve been able to form a serration that is going to withstand the repeated forces needed to eat because eating is important. So, there’s a lot of selection acting on teeth,” Whitney said.

Gorgonopsians were a diverse group with body sizes that ranged from the size of a medium-sized dog to a bear. Whitney noted that although the specimens sampled had this type of morphology, it remains possible that there is a diversity of serration types that would match the diversity of gorgonopsians.

The study, “Convergent Dental Adpatations in the Serrations of Hypercarnivorous Synapsids and Dinosaurs,” was published by Biology Letters.

Related Articles

Dental Traits Reveal Genetic Relationships Between Human Beings

Ancient Plaque Reveals Exotic Diets 3,700 Years Ago

Ancient Enamel Reveals Ancestors’ Role in Human Family Tree