The consumption of sugary drinks in the diverse and low-income neighborhoods of Berkeley, California, dropped precipitously in 2015 just months after the city levied the nation’s first tax on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), according to the University of California at Berkeley. Now, researchers at the school note, residents in these neighborhoods report drinking 52% fewer servings of SSBs than they did before the tax was passed in November 2014.

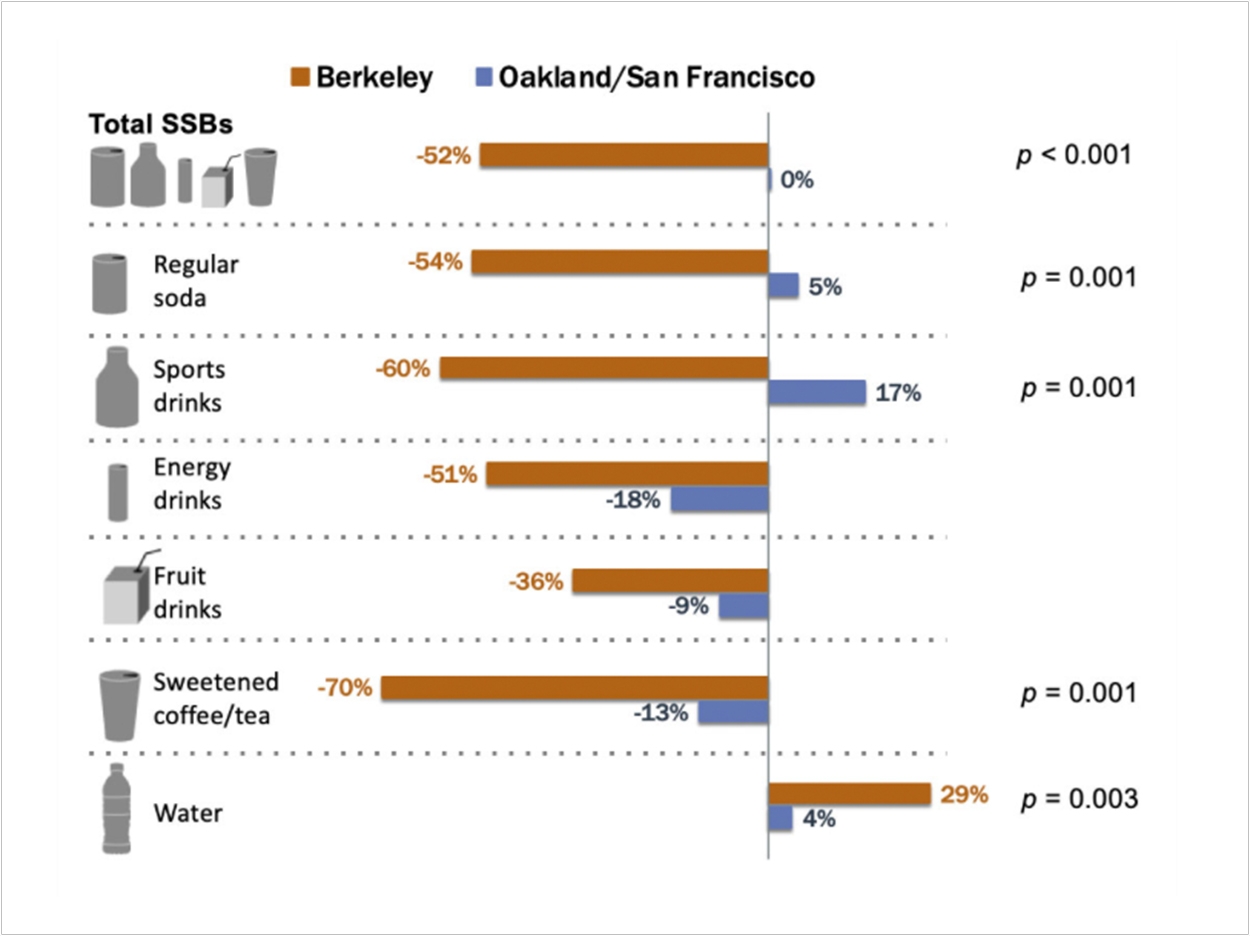

The drop more than doubles the 21% decline found in 2015, the researchers say. Also, Water consumption increased 29% over the three-year period. The researchers add that their study, which is the first to document the long-term impacts of a soda tax on drinking habits in the United States provides strong evidence that such taxes are effective in encouraging healthier drinking habits, with the potential to reduce diseases such as diabetes and tooth decay.

“This just drives home the message that soda taxes work,” said Kristine Madsen, faculty director of the Berkeley Food Institute in UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health. “Importantly, our evidence comes from low-income and diverse neighborhoods, which have the highest burden of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, not to mention a higher prevalence of advertising promoting unhealthy diets.”

The researchers say their study comes at a critical time for local governments that are considering taxes on SSBs. While cities such as Philadelphia and Seattle now have soda taxes on the books, California and Washington passed bills in 2018 banning municipalities in those states from enacting soda taxes in the future. The bulk of Berkeley’s soda tax revenue is dedicated to supporting nutrition education and gardening programs in schools and to local organizations working to encourage healthier behaviors in the community.

“Sugar-sweetened beverages, which are linked to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, cost our nation billions of dollars each year, but they are super-cheap. They’d cost much more if the healthcare costs were actually included in the price of the soda,” Madsen said. “Taxes are one way of taking those costs into account.”

Madsen and her team have been tracking the drinking habits of residents of low-income and diverse neighborhoods in Berkeley since 2014, when 76% of voters approved a penny-per-ounce tax on all SSBs. While the excise tax is levied on distributors, rather than directly on consumers, studies have shown that retailers have incorporated the higher costs into the shelf price of the drinks.

To determine residents’ drinking habits, the team polls about 2,500 people each year in intersections with high foot traffic in racially and demographically diverse neighborhoods across Berkeley, Oakland, and San Francisco. Berkeley saw an overall decrease in SSB consumption between 2014 and 2017, especially for soft drinks like Coke and Pepsi, sports drinks like Gatorade and Powerade, and sweetened teas and coffees.

Residents of Oakland and San Francisco drank about the same number of sugary beverages in 2017 as they did in 2014, suggesting that these changes were unique to Berkeley and not signs of a regional trend in drinking habits unrelated to the tax. Oakland and San Francisco have since enacted their own soda taxes, going into effect in 2017 and 2018, respectively.

Yet Madsen says that the study does have its limitations. Street intercept surveys do not provide a random sample or residents. Also, Berkeley is a relatively small and highly educated city. Price hikes might not be the only driving factor behind the change as well, Madsen adds, since taxes also send a message about societal values, which can have a big impact on consumer behavior.

“There are some earlier studies out of Berkeley that suggest that the messaging alone is effective at reducing consumption,” Madsen said. “But people are still very much affected by what hits their pocketbooks.”

But the similarity between these results and other long-term results in Mexico, which also saw increased effects of its soda tax over time, suggest that these measures can be a powerful tool in the fight against diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and tooth decay, the researchers report.

“I really want to push back against this idea that taxes are the sign of a nanny state,” Madsen said. “They are one of many ways to make really clear what we value as a country. We want to end this epidemic of diabetes and obesity, and taxes are a form of counter-messaging to balance corporate advertising. We need consistent messaging and interventions that make healthier foods desirable, accessible, and affordable.”

The study, “Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption 3 Years After the Berkeley, California, Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax,” was published by the American Journal of Public Health.

Related Articles

CDA and CMA Team Up to Take On Big Soda

IADR and AADR Divest Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Companies From Portfolio

Tax Reduces Sugary Beverage Consumption in Berkeley