The practice of dental hygiene is ever-changing as the scientific community allocates more time toward (and discovers more details of) how periodontal disease actually begins and reappears in the dentition. A generation ago, clinicians thought and were taught that gingivitis was the early stage of periodontal disease, that all bacteria in the oral cavity were harmful, that anyone with a dentition was a candidate for periodontal disease, and that oral hygiene and age were risk factors. Things have changed! Current thinking and research leads us to believe that gingivitis is reversible and is not an indication of periodontal disease after all.1

Today, we know the pathogenesis of periodontitis is bacteria affecting the host cells by releasing host mediators and causing breakdown of the connective tissue—an inflammatory response—and alveolar resorption. The offending bacteria are organized by the way they live and work in the mouth. Research shows that the “red and orange complex” bacteria are the groups that destroy the periodontium. This appears clinically as increased pocket depths and loss of attachment and/or bone loss visible on radiographs, all of which can be identified during the periodontal examination. Data suggest that fully 80% of the adult population of the United States suffers from periodontal disease.2 The effects can be irreversible, leading to tooth loss and a host of debilitating sequelae.

Microscopically, we have more information regarding these bacteria. In the late 1980s, scientists turned to engineers to develop a microscope they could use to study biofilms. While environmentalists had been studying biofilms for some time, what technology helped us see was that biofilms also exist in the oral cavity. As elsewhere, plaque biofilms are attracted to the protein-rich pellicle and develop into highly organized colonies. Bacteria establish an irreversible contact using sticky polysaccharide slime. Cell division occurs in this slime, and mushroom-shaped colonies develop, attached to tethers. Fluid fills the channels between the colonies, providing nutrition for the bacteria and communication. This research and technologic advance made it clear that removal and control of the microbiofilms are the critical part of treating and controlling periodontal disease.2

In addition to research on biofilms and their impact on disease, the body’s response to inflammation is also a risk factor. Levels of mediators found in the gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) can be measured and used to evaluate the risk of periodontal disease. The collection of this fluid is a simple process, though diagnostic test kits are presently expensive and not widely available. Studies also suggest that while the disease may be evident in specific areas, periodontal disease may affect the entire mouth.2

These changes in procedures and protocols can be overwhelming for both the hygienist and doctor. Patients who have been accustomed to a focus on routine hygiene “cleanings” may also find themselves questioning the new information regarding their condition. It may be difficult at best to convince a patient that what was being done before is not enough now. The routine visit now will include specific medical history questions, medication analysis, home care instructions that are specific to each patient in the family, periodontal charting, and finally the cleaning. It is a lot to explain in a short time, especially when the emphasis is new. The staff and the doctor must be on the same page and learn to communicate carefully regarding the examination at each visit. Scheduling of the patient is more complicated and specific now. There will be instances where family members who have been coming to the office together for years will be on different schedules. Accommodations must be made for easing the patient through the new “hoops to health.”

As professionals, we work hard to keep up with the latest scientific thoughts on the progression of periodontal disease as well as the latest information available on topics like biofilms, locally applied antimicrobials, and fluoride products to control the biofilms. In 1998, a book titled Who Moved My Cheese? was written by Spence Johnson, MD,3 and rapidly became a best seller. I speak with many hygienists who have read that book. They understand that while they may be comfortable in the older, familiar practice with patients they care about, know, and want to continue to treat, the thought of being a periodontal therapist is not where their comfort level is. They have spent the better part of their careers treating patients in a certain way, discussing dentistry and oral hygiene care in a similar way with all patients—children and adults alike—and are reluctant to make a change.

It is difficult to understand the changes and perhaps more difficult to communicate those changes to patients. Much is written today to link periodontal disease with heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and low-birthweight babies. While dental professionals are being reinstructed about disease and the link between the various microbes and their processes, patients are being bombarded with messages about cosmetics to improve their appearance. A disconnect is evident when a patient wants whitening and you, as the hygienist, see pocketing, inflammation, bleeding, and risk factors for many other problems. How can you convince your patients that the disease process is no longer solely about decay if you are not totally immersed in the new information?

The reality is that the practice of dental hygiene has changed and can only continue to evolve. As Dr. Johnson says in his book, “If you do not change, you could become extinct.”3 The main thrust of Dr. Johnson’s book is learning to change and appreciating change. All dental professionals must work to understand and begin to appreciate change as it occurs. Knowledge through continued education and discussions with practicing periodontal therapists and local periodontists will move the clinician into the 21st century. I now tell hygienists to “move with the cheese and enjoy it.”3

For periodontal therapy to be effective, the differences in care revolve around careful and thoughtful use of evidence-based information that is used to design optimal treatment options for each patient. The evidence-based findings begin with thorough patient assessment and an oral tissue examination to establish a threshold level for risk. After a discussion with the patient about his or her perception of the dentition, the clinician must closely review all aspects of the medical history. A cursory “any changes in your medical history?” should be replaced with a complete review of medical conditions, hospitalizations, medications (herbal, over-the-counter, and prescription), and other pertinent information, such as stress-induced headaches, lack of sleep, xerostomia, etc.

Patients reluctant to give you specific information may simply need to be told that there are reasons to believe that conditions in the mouth can reflect or help diagnose the possibility of systemic problems. For example, information on the number of people dying each year (over 8,000) from oral cancer has a positive effect on the number of patients who allow the palpation of the head and neck.

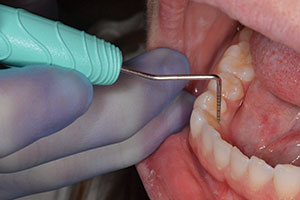

What is becoming known is that risk factors include heart disease, diabetes, immune system diseases, and previous periodontal history. These unchanging risk factors contribute to the overall susceptibility of the patient to the disease. Moving into the actual periodontal examination, a probing of 6 sites per tooth is necessary to have a complete evaluation of tissue, bone loss, and loss of clinical attachment. Bleeding on probing should be recorded. The periodontal examination is part of the changing risk factors as well as tobacco use, poor oral hygiene, stress, or excessive alcohol use. Radiographs are also taken and evaluated for documentation of any change that is occurring. Routine bitewing films and current full-mouth x-rays are standard for the care of adult patients. After careful assessment based on experience and the evidence, the correct treatment plan must be presented to the patient. In working with dental offices in the Atlanta area, I have found this to be an area of confusion. Let’s look at the different types of appointments given on a regular basis from the hygiene dept.

Prophy (D1110). The term for dental prophylaxis is used to treat patients with findings of no periodontal pockets greater than 4 mm and 10 to 15 maximum bleedings on probing. This is the healthy adult patient with supracalculus and very little subcalculus.

Seeing greater numbers of bleeding on probing would require treatment for gingivitis.

When pockets are found greater than 4 mm, it must be determined if the entire mouth needs nonsurgical therapy or only specific areas. D4341 is used for the full quadrant of teeth (or the majority of teeth) needing treatment.

D4342 is used with 3 teeth or fewer in the quadrant needing nonsurgical therapy. This is an often-diagnosed treatment for the patient. Early detection and frequent periodontal exams will find the areas with early breakdown. As little as one tooth can be treated with nonsurgical therapy to maintain the patient’s periodontal health.

I find debridement (D4355) to be the most misused dental procedure in offices I work with. This procedure is used when removing large amounts of calculus in order to be able to perform an accurate periodontal exam and make a correct diagnosis of the type of future procedures this patient will need. In many offices, this debridement procedure is the cover for more “super prophies.”

Now let’s discuss periodontal maintenance. This maintenance appointment is where dental professionals help patients maintain the health they have attained from nonsurgical or surgical procedures. It must be made very clear to patients how important and how different this is from the prophy they had always received prior to their treatment. This maintenance treatment is typically scheduled every 3 months, but refractory periodontal patients may need to be seen every 8 weeks. The clinician may see a patient with fewer, less involved areas of bone loss at a 4-month recare schedule. This must be assigned as each patient’s needs dictate. These patients are periodontal maintenance patients and will always remain periodontal maintenance patients. The periodontal patient must also be informed of all changes in the oral cavity and any prognosis change. As with the prophy appointment, each periodontal maintenance patient must have updated medical and dental histories as well as needed radiographs. Assessment of oral hygiene must be performed at each visit and instructions given for that individual’s needs.

With the nonsurgical appointments and the periodontal maintenance appointments, the placement of chemotherapeutic agents (D4381) may be necessary. The Academy of Periodontology stated the following in its Guidelines for Periodontal Therapy position paper in September 2001: “These agents may be used to reduce, eliminate, or change the quality of microbial pathogens or alter the host response through local or systemic delivery.”4 The standard of care is to place chemotherapeutic agents in any area with bone loss, 5-mm pockets, and bleeding on probing. The periodontal pockets are areas of bacterial infection and chronic inflammation. New evidence has been presented suggesting that chronic inflammation is the underlying link to major diseases in the human body. Time magazine had a great article on the subject in its February 23, 2004 issue. (Remember, too, that patients are reading new information about periodontal disease in the media.)

If your office is accurately diagnosing periodontal disease, you will find that the bulk of your appointment procedures will be periodontal maintenance. A good portion will be nonsurgical therapy, and a slight percentage will be the prophy procedure. A simple report from a quarter this year and the same quarter last year will be a good indicator of your practice. What percentage would you find to be D1110 versus D4910?

CONCLUSION

As hygienists move into the new century of preventive care, they will find great professional gratification in understanding that the control of periodontal disease is of great importance to the holistic health of the patients for whom they care. Much has been published about studies linking periodontal disease as a risk factor for heart and lung disease, diabetes, respiratory disease, etc. Educating patients is as important in today’s practice as good individual oral hygiene techniques. The ability to communicate that important information in a format the patient can understand and appreciate is vital to the health of the patient and the practice. Your appointment time with each patient is critical to building a rapport and a bridge linking the old information to the new. Your doctor should appreciate that you have increased your knowledge base and that you are not afraid of growth and change. The return on your knowledge is exponential and can be easily viewed with each patient visit. Caring and concern for health does not diminish with change. It refines and refocuses our ability to assist each patient to gain better health.

Assess where you are in terms of being evidence-based and diagnosis-driven in your practice. Remove any old phrases such as “deep cleanings” and “appointments for cleanings” and replace them with phrases such as “nonsurgical therapy” and “hygiene appointment.” Work hard to bring your patients up to date on current information, and bring your hygiene department up to date. Look at the equipment you are using. How old are those periodontal probes, and where are the markings? When did you last replace the ultrasonic tips? Do the curettes have enough face to actually sharpen? Are new instruments needed? These instruments are important in the proper treatment of your patients. Do you have enough educational material to help patients understand their disease and infection?

Answer patient questions, have brochures available that explain disease concepts and new thought, and refer the technologically advantaged to Web sites for further study. Patient compliance will soar, and you will have great satisfaction knowing you provide the best care available today.

But get ready. As more research is completed and new products surface, your “cheese” will move again, and “movement in a new direction helps you find new cheese.”4

References

1. Williams RC. Current Concepts in Initiation and Progression of Periodontal Disease. Paper presented at: Proctor & Gamble symposium Exploring Periodontal Disease in the 21st Century; September 1995.

2. Costerton JW, Cheng KJ, Geesey GG, et al. Bacterial biofilms in nature and disease. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:435-464.

3. Johnson S. Who Moved My Cheese? An Amazing Way to Deal With Change in Your Work and in Your Life. Chicago, Ill: Putnam Pub Group; 1998.

4. Greenwell H; Committee on Research, Science and Therapy. American Academy of Periodontology. Position paper: Guidelines for periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1624-1628.

Ms. Berkesch is a practicing periodontal therapist in Atlanta, Ga. She also is a clinical educator for Orapharma and owner of Perio Protocols, a consulting firm specializing in creating a diagnosis-driven team. She can be reached at (770) 355-3481 or at Cheryl@Berkesch.com.