A Conservative Aesthetic Rehabilitation in an Adolescent

INTRODUCTION

Pediatric odontogenic tumors are rare but can lead to developmental consequences resulting in issues regarding aesthetics and the functionality of a patient’s dentition.1 A majority of these tumors are benign if diagnosed early. A collaboration between multiple specialties is often necessary to acquire an optimal outcome.1 The most aggressive benign lesions and malignant tumors require major surgery with immediate or delayed reconstruction.2

In addition, the adaptation of procedures to accommodate a patient’s medical and social needs is necessary to maintain patient satisfaction and adherence. Although benign, if not treated appropriately, it can become life-threatening.

The World Health Organization (WHO) divided odontogenic tumors into 3 classifications of odontogenic tumors and cysts based on biologic behavior: epithelial, mesenchymal, and mixed epithelial and mesenchymal odontogenic tumors. Each category is defined based on tissue analysis from the tumors.3

Myxoma, one of the benign odontogenic tumors, arises from embryonic connective tissue associated with tooth formation. The term “myxoma” was first used in 1863 to describe abdominal and soft-tissue lesions.4,5 A myxoma consists mainly of spindle-shaped cells and scattered collagen fibers distributed through a loose, mucoid material.5

The recommended treatment is usually surgical excision. Approaches can be conservative, enucleation and curettage, curettage, or wide resection with or without bone grafting, depending on the size of the tumor.6

CASE REPORT

A 12-year-old male presented with his parents with a chief complaint of “replacing missing teeth.” The patient’s health history included prior resection of a spindle cell myxoid tumor of the left posterior maxilla in infancy, unilateral growth disturbance, and a diagnosis of autism.

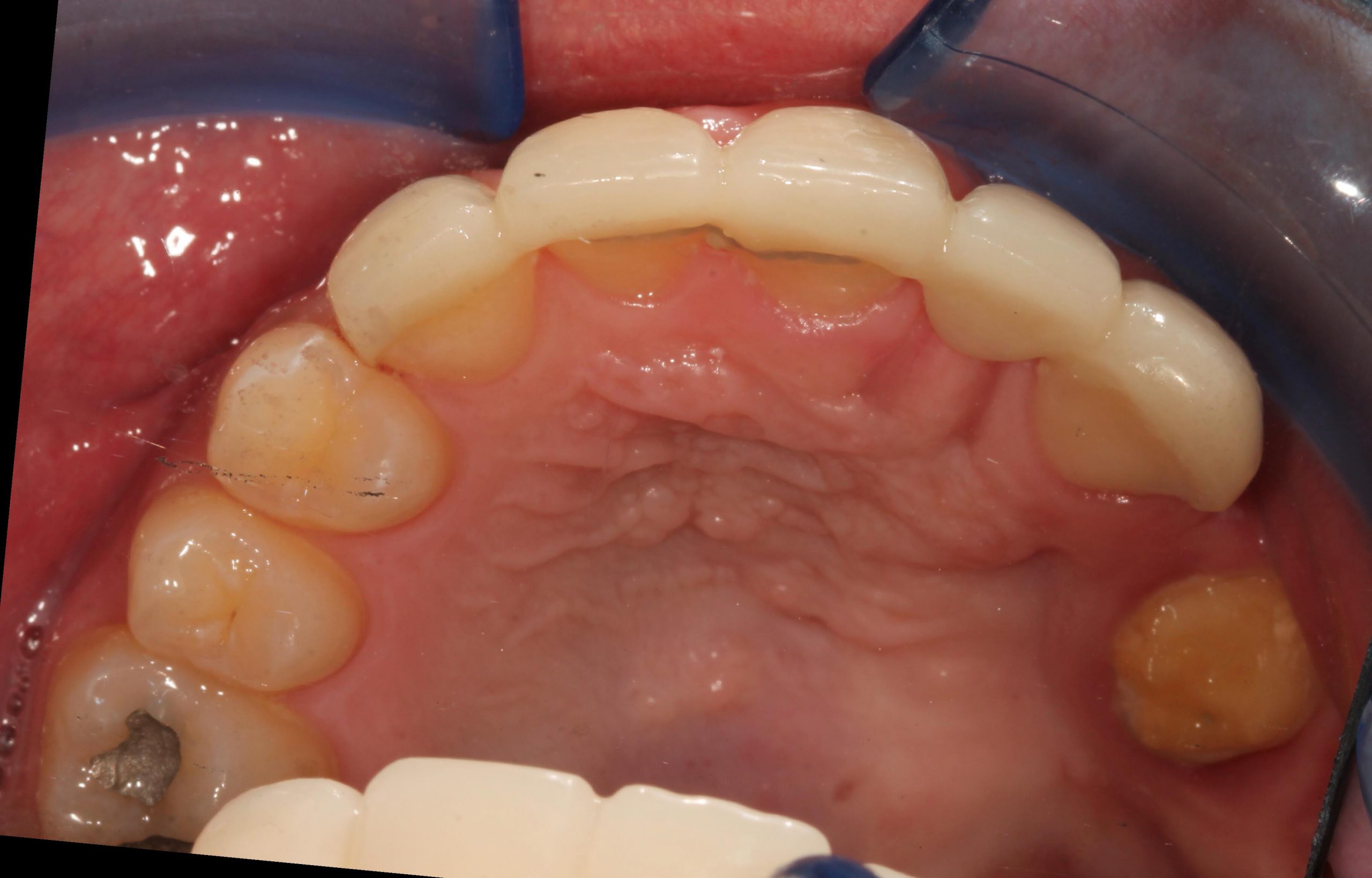

The head and neck exam was negative for any lymphadenopathy and was within normal limits. Intraoral examination demonstrated missing teeth on the maxillary left side (Figures 1 and 2). A large factor was the fact that the patient had a prominent gag reflex and cannot tolerate long chair times nor anesthesia or drilling.

The panoramic radiograph confirmed the agenesis of the maxillary left side teeth from the lateral incisor to the third molar (Figure 3). According to both parents, the patient was a shy child, socially anxious, and had difficulty socializing and smiling in public (Figure 4).

After the diagnosis, the treatment plan was created as a temporary approach and with the understanding of the patient’s issues noted above. Thorough clinical examination was done; radiographs and preliminary scans were taken prior to treatment; and consultations with an oral surgeon, an orthodontist, and a prosthodontist were obtained. Following patient approval, orthodontic treatment was started in order to create the necessary spacing to re-create the patient’s midline (Figures 5 to 7).

Following 1.5 years of orthodontic treatment, the patient’s dentition was restored conservatively using a prepless, scanned, milled composite temporary bridge. Once the patient has finished growing, orthognathic surgery and implant placement will be performed.

Treatment Objective

According to the diagnosis, the goals of this temporary treatment plan included space closure, establishing his smile, and replacing the missing teeth for improvement of phonetics, function, and aesthetics. The patient refused any treatment on the mandibular arch other than keeping it in regular maintenance.

Methods and Materials

Treatment planning was based on understanding the patient’s limitations around chair time, local anesthesia, drilling, and wearing a removable appliance due to a prominent gag reflex, as previously noted. A thorough clinical examination was done, and radiographs and preliminary TRIOS (3Shape) scans were taken prior to treatment.7 One of the advances of this technology that uses intraoral scans and digital models, in this particular case, is a promising alternative to conventional impressions in regard to patient acceptance and efficiency.8

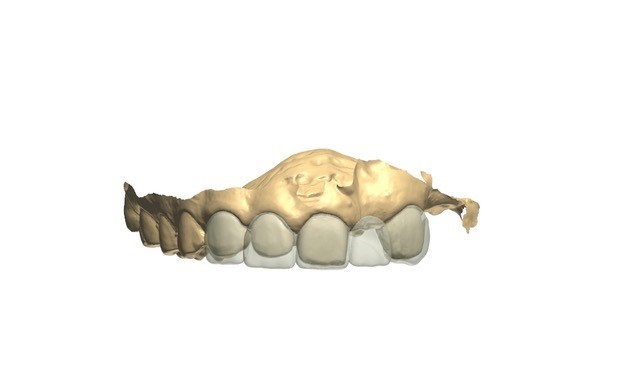

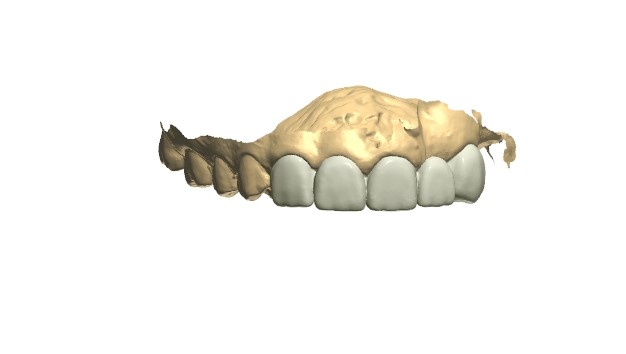

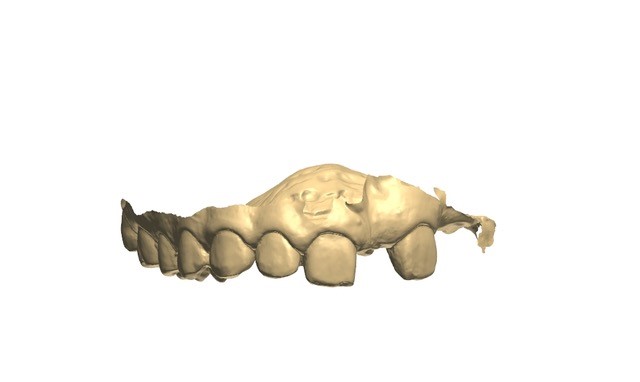

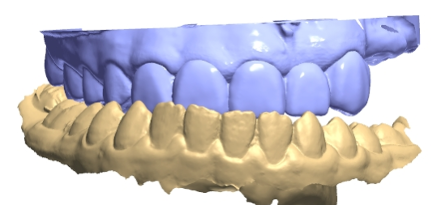

Consultations with an oral surgeon, an orthodontist, and a prosthodontist were obtained. Following caregiver approval, orthodontic treatment was started in order to create the necessary spacing to re-create the patient’s midline. One year later, a new TRIOS scan was obtained for a diagnostic wax-up (Figures 8 to 10). After evaluating the scan, patient smile, and occlusion, the teeth distribution was acceptable to finalize the treatment (Figures 11 and 12). A composite overlay bridge using SR Vivodent CAD (Ivoclar Vivadent) was created.

A 38% phosphoric acid etch (Scotchbond Universal Adhesive [3M]) and A2 Tetric EvoFlow Refill (Ivoclar Vivadent) were used as a cement to stabilize the bridge.9,10 Occlusion was adjusted for even contact in centric relation (Figures 13 to 15).

Patient satisfaction with the digital impression experience resulted in comfort, reduced dental chair time,11-13 and less anxiety.14,15

Digital dentistry techniques improve the quality of oral rehabilitations, especially in anxious patients, by having higher acceptance rates compared to conventional techniques.11-15

CONCLUSION

Conservative provisional treatment of a significantly impaired patient can be predictably accomplished using lower-cost composite materials and digital scanning and CAD/CAM restorations (Figure 16). Once the patient matures, orthognathic surgery and implant placement will be performed.

References

1. Abrahams JM, McClure SA. Pediatric odontogenic tumors. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2016;28(1):45-58. doi:10.1016/j.coms.2015.08.003

2. Shamim T. The spindle cell neoplasms of the oral cavity. Iran J Pathol. 2015;10(3):175–84.

3. Soluk-Tekkeşin M, Wright JM. The World Health Organization Classification of Odontogenic Lesions: A summary of the changes of the 2017 (4th) edition. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2018;34(1). doi:10.5146/tjpath.2017.01410

4. Alhousami T, Sabharwal A, Gupta S, et al. Fibromyxoma of the jaw: case report and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2018;12(1):44-51. doi:10.1007/s12105-017-0823-0

5. Hajdu SI, Vadmal M. A note from history: Landmarks in history of cancer, Part 6. Cancer. 2013;119(23):4058–82. doi:10.1002/cncr.28319

6. Covello P, Buchbinder D. Recent trends in the treatment of benign odontogenic tumors. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;24(4):343–51. doi:10.1097/MOO.0000000000000269

7. Nedelcu R, Olsson P, Nyström I, et al. Accuracy and precision of 3 intraoral scanners and accuracy of conventional impressions: a novel in vivo analysis method. J Dent. 2018;69:110–8. doi:10.1016/j.jdent.2017.12.006

8. Burzynski JA, Firestone AR, Beck FM, et al. Comparison of digital intraoral scanners and alginate impressions: time and patient satisfaction. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018;153(4):534–41. doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.08.017

9. Ivoclar website. SR Vivodent CAD. https://www.

ivoclarvivadent.us/explore/sr-vivodent-cad.

10. Vivadent I. Tetric EvoCeram® Bulkfill: simplifies composite restoration placement, increases efficiency. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2014;35(6):432.

11. Burhardt L, Livas C, Kerdijk W, et al. Treatment comfort, time perception, and preference for conventional and digital impression techniques: A comparative study in young patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2016;150(2):261–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.12.027

12. Burzynski JA, Firestone AR, Beck FM, et al. Comparison of digital intraoral scanners and alginate impressions: time and patient satisfaction. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018;153(4):534–41. doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.08.017

13. Yuzbasioglu E, Kurt H, Turunc R, et al. Comparison of digital and conventional impression techniques: evaluation of patients’ perception, treatment comfort, effectiveness and clinical outcomes. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:10. doi:10.1186/1472-6831-14-10

14. Grünheid T, McCarthy SD, Larson BE. Clinical use of a direct chairside oral scanner: an assessment of accuracy, time, and patient acceptance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;146(5):673–82. doi:10.1016/j.ajodo. 2014.07.023

15. Mangano A, Beretta M, Luongo G, et al. Conventional vs digital impressions: acceptability, treatment comfort and stress among young orthodontic patients. Open Dent J. 2018;12:118–24. doi:10.2174/1874210601812010118

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Boyd graduated from the Columbia University College of Dental Medicine in New York City. He completed a residency program in general dentistry and prosthodontics from the US Department of Veterans Affairs in New York City. He now has a private practice in Midtown Manhattan—Drs. Boyd, PC—and holds a faculty position at the Touro College of Dental Medicine as an associate clinical professor. Dr. Boyd can be reached via email at drandrew@drsboyd.com.

Dr. Paranhos graduated from the Universidade de Odontologia João Prudente in Brazil. She then continued her education in the United States at the New York University College of Dentistry (NYUCD) Ashman Department of Periodontology and Implant Dentistry and received a postgraduate degree and Fellowship in implant dentistry. This was followed by an international postgraduate program in periodontics.

She also completed an Advanced Education in General Dentistry (AEGD) Postdoctoral Program at the University of Rochester Eastman Institute of Oral Health and received an accredited DDS degree as well as a master’s degree in dental science. She recently received her Diplomate status in implant dentistry from the International Congress of Oral Implantologists.

Dr. Paranhos has been teaching at the NYUCD Implant Department for 9 years and is currently a clinical assistant professor/assistant group practice director in the Cariology & Comprehensive Care Department at NYUCD. She maintains a private practice in Manhattan and can be reached at kp21@nyu.edu.

Dr. Seligman earned his degree at the University of Connecticut School of Dental Medicine and his specialty certificate at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Division of Orthodontics. An orthodontic specialist, he is in private practice in Manhattan at Seligman Orthodontics PLLC.

Disclosure: The authors report no disclosures.