In this era of COVID-19, dentists are reporting increased numbers of patients presenting with cracked teeth (Shannon 2020). The mechanism for crack development is concentrated repetitive stress with subsequent fatigue of enamel and then dentin.

Presumptively, the mental and emotional stress of the pandemic and adhering to strict state or local guidelines to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 has led to a higher incidence of bruxism and grinding, though no studies have examined incidence during “stressful” periods of time.

Regardless, studies have shown that with the earlier the diagnosis of cracked teeth, the less likely there will be progression to pulpal pathosis requiring endodontic treatment (Krell and Rivera 2007; Abbott and Leow 2009; Opdam, Roeters et al 2008). This makes early diagnosis the key to managing treatment.

Management of cracked teeth can be challenging. Not only do patients with cracked teeth present with varying symptoms and clinical presentations, but survey studies also indicate a lack of consensus within the dental community regarding cracked tooth treatment protocols (Alkhalifah, Alkandari et al 2017).

Treatment Planning

An accurate endodontic evaluation is the first critical step in proper management of cracked teeth. The patient’s symptoms along with the crack’s orientation, depth, and pulpal and periodontal involvement dictate the appropriate restorative approach.

|

|

Figure 2. (A) Microscopic view internally of a deep radicular crack extending 3 mm beyond the level of the canal orifice (arrow) and (B) deep orifice resin-modified glass ionomer placed 2 to 3 mm apical to the extent of the crack. (From Davis and Shariff 2019, Success and survival of endodontically treated cracked teeth with radicular extensions: a 2- to 4-year prospective cohort, Journal of Endodontics, 2019 (45), pages 848-855.) |

|

| Figure 3. Iowa Staging Index with associated success rates (From Krell and Kaplan, 12-month success of cracked teeth treated with orthograde root canal treatment, Journal of Endodontics, 2018 (44), pages 543-548.) |

|

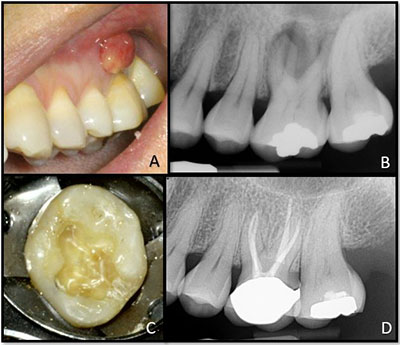

| Figure 4. (A, B) Cracked tooth No. 14 with sinus tract and a diagnosis of pulpal necrosis with chronic apical abscess. (C) Facial-lingual crack that extended 3 mm subgingivally on the lingual. (D) 4.8-year post-operative periapical radiograph showing complete bony healing. |

|

| Figure 5. (A) Cracked tooth No. 3, (B) with the occlusal amalgam removed, (C, D) endodontic treatment complete showing multiple cracks extending well into the MB2, DB, and P canals, and (E) orifice barriers placed. (F, G) Post-operative and 4-year radiographs respectively. |

Also, pulp and periapical testing, periodontal probing, transillumination, isolated bite pressure testing, dyes, radiographic evaluation, and a microscopic exam are important adjuncts that together yield necessary information for treatment planning the cracked tooth.

Craze lines, confined to enamel, rarely require restorative treatment unless they pose a cosmetic issue for the patient. Because they do not extend into dentin, the pulp is not affected. Therefore, teeth with craze lines do not require endodontic treatment. In contrast, split teeth and vertical root fractures are by and large deemed hopeless and are relegated to extraction (Rivera 2008).

Asymptomatic cracks are prevalent in adult posterior teeth, typically appearing on marginal ridges or grooves. While some cracks may propagate apically over time, many remain unchanged (Figure 1).

Since there are no current studies indicating the risk or incidence of further progression of the crack over time, clinicians face the dilemma of whether a proactive approach in crown placement or a more conservative “watch” should be recommended.

In some cases, it may be judicious to adjust occlusion ensuring light contacts and eliminating excursive interferences from the more vulnerable areas of these teeth (eg, lingual cusps of maxillary premolars). A night guard may be another preventative measure in patients exhibiting cracked teeth.

When symptomatic, cracked teeth and cuspal fractures require a full-coverage coronal restoration when possible (Ailor 2000). In cases where the pulpal diagnosis is deemed reversible pulpitis, no endodontic intervention is required, and a crown should be placed as soon as possible.

Studies following these symptomatic cracked teeth that were crowned had similar rates of later requiring root canal treatment as those non-cracked crowned teeth (Krell and Rivera 2007, Abbott and Leow 2009). With a pulpal diagnosis indicating irreversible endodontic disease (irreversible pulpitis or pulpal necrosis), root canal treatment should precede crown placement.

Treatment and Prognosis

During root canal treatment, an endodontist can assess a crack’s internal depth microscopically. In cases of deeper cracks with a radicular extension (into root dentin), intra-orifice barriers placed apically to the apical extent of the crack may provide a protective coronal seal, thereby mitigating bacterial ingress into the canal as well as possibly reinforcing the critical cervical dentin level of the tooth (Davis and Shariff 2019) (Figure 2).

Following root canal treatment, the cracked tooth should be taken entirely out of occlusion with no excursive contact. Patients must be informed of the cracked tooth’s vulnerability proceeding the placement of the full-coverage restoration. They should be instructed to avoid mastication on the affected tooth’s side and to set the crown appointment posthaste.

It is unnecessary to delay crown preparation and placement in favor of “allowing the

tooth to heal” post-endodontically. Proper endodontic treatment very rarely requires retreatment within the first few months. Therefore, the risk of further propagation of the crack due to delaying the protective restoration likely far outweighs the probability of the necessity of endodontic revision. Proper restoration of endodontically treated teeth is a significant factor in long-term retention (Aquilino and Caplan 2002).

Occlusion is an important factor for the longevity of cracked teeth. At the time of delivery of the final restoration, care must be taken to ensure light contacts with no excursive interferences. This should then be re-evaluated at six weeks following crown cementation.

In their prospective study on cracked teeth, Davis and Shariff found that occlusion needed to be re-adjusted in 79% of cases at six weeks post-crown (Davis and Shariff 2019). Patients’ parafunctional habits should be addressed, and a night guard should also be considered.

With proper management, cracked teeth can carry a favorable prognosis. In one six-year study, progression of interproximal periodontal defects associated with crowned cracked teeth only occurred in 4% of cases. Also, those later requiring endodontic intervention occurred at approximately the same rate as non-cracked crowned teeth (Krell and Rivera 2007). This likely points to the long-term importance of full cuspal coverage restorations and that once crowned, cracked teeth behave similarly to non-cracked crowned teeth.

Multiple outcome studies validate a favorable prognosis for endodontically treated cracked teeth with survivals ranging from 86% to 97% (Tan, Chen et al 2006; Kang, Kim et al 2016; Sim, Lim et al 2016; Davis and Shariff 2019). Using stringent outcomes criteria, a success rate of 82% at one year also was found (Krell and Caplan 2018). Further bivariate analysis from that study resulted in the Iowa Staging index (Figure 3).

In a prospective study of teeth with deep cracks extending onto the root surface, Davis and Shariff found a success rate of 91% and survival of 97% when employing modern microscopic endodontic technique as well as the aforementioned postoperative management protocols (Figures 4 and 5).

Conclusion

New studies, technologies, and advances in dental materials and techniques have allowed us to find more ways to save teeth. With growing concern over untoward implant complications along with patients’ desire to try to save their natural tooth, restoring a cracked tooth would seem to be the overall treatment of choice.

Certainly, case selection and myriad patient variables must be considered when having effective dialogue with patients when conveying options, expected outcomes, and contingencies.

Undoubtedly, a thorough discussion of all parameters must take place with our patients before proceeding, but today’s modern endodontic approaches are allowing what were once deemed “hopeless” teeth a much improved chance for survival, success, and function.

Bibliography

Abbott P and Leow N (2009). Predictable management of cracked teeth with reversible pulpitis. Aust Dent J 54(4): 306-315.

Ailor JE Jr (2000). Managing incomplete tooth fractures. J Am Dent Assoc 131(8): 1168-1174.

Alkhalifah S et al (2017). Treatment of Cracked Teeth. J Endod 43(9): 1579-1586.

Aquilino SA and Caplan DJ (2002). Relationship between crown placement and the survival of endodontically treated teeth. J Prosthet Dent 87(3): 256-263.

Davis MC and Shariff SS (2019). Success and Survival of Endodontically Treated Cracked Teeth with Radicular Extensions: A 2- to 4-year Prospective Cohort. J Endod 45(7): 848-855.

Kang SH et al (2016). Cracked Teeth: Distribution, Characteristics, and Survival after Root Canal Treatment. J Endod 42(4): 557-562.

Krell KV and Caplan DJ (2018). 12-month Success of Cracked Teeth Treated with Orthograde Root Canal Treatment. J Endod 44(4): 543-548.

Krell KV and Rivera EM (2007). A six-year evaluation of cracked teeth diagnosed with reversible pulpitis: treatment and prognosis. J Endod 33(12): 1405-1407.

Opdam NJ et al (2008). Seven-year clinical evaluation of painful cracked teeth restored with a direct composite restoration. J Endod 34(7): 808-811.

Rivera RM and Walton RE (2008). Cracking the cracked tooth code: detection and treatment of various longitudinal tooth fractures. Colleagues for Excellence, 2008.

Shannon J (2020). Cracked teeth, gross gums: dentists see surge of problems, and the pandemic is likely to blame. USA Today Published 9-11-2020: 3.

Sim IG et al (2016). Decision making for retention of endodontically treated posterior cracked teeth: a 5-year follow-up study. J Endod 42(2): 225-229.

Tan L et al (2006). Survival of root filled cracked teeth in a tertiary institution. Int Endod J 39(11): 886-889.

Dr. Krell is immediate past president of the American Association of Endodontists and a Diplomate of the American Board of Endodontics. He has been an endodontist for 39 years. He is an adjunct clinical professor in the Department of Endodontics at the University of Iowa College of Dentistry, where he also served as graduate program director until 1989. In 1993, he retired from the United States Army National Guard as a lieutenant colonel after 22 years of service. In 2018, he retired from full-time private practice, but since then has been providing part-time care to patients at Broadlawns Medical Center in Des Moines, Iowa.

Dr. Davis is an endodontist in private practice in Glenview and Winnetka, Illinois. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Endodontics. He has been a full-time practitioner for 20 years. He attended the University of Iowa College of Dentistry, where he received his DDS in 1999 and his specialty certificate in endodontics in 2001. While there, he was awarded the American Association of Endodontists’ Student Achievement award in 1999, and he taught at the University of Iowa for a short time prior to going into private practice.

Related Artilcles

Q&A: COVID-19 Treatment With AAE President Dr. Keith V. Krell

Endodontic Emergencies Peak During COVID-19

AAE Guidelines Separate Emergency and Non-Emergency Treatment