Radiographs are an essential part of proper diagnosis. As dentists, we should make sure that operators do not take for granted the impact of their actions when they take x-rays. They may hurry through the process or may not thoroughly understand all of the factors that comprise the process.

Radiographs are taken when you, the dentist, orders them based on intraoral examination and following review of the patient’s medical history. This is the time for the operator to endeavor for the best image quality possible. Attaining that “best image” relies on the operator’s knowledge of radiation exposure and proper positioning.

A good radiograph will ensure a good diagnosis and thus proper treatment of the patient. Taking that x-ray correctly the first time will save the patient unnecessary radiation exposure and save the practice time and expense.

RADIATION EXPOSURE

All of us are exposed to different types of radiation on an ongoing basis. We have little control over this exposure. However, what we as dentists do have control over is the radiation we dispense.

To obtain images of the oral cavity one must at all times be aware of our basic rule: ALARA. This means we are taking images using As-Low-As-Reasonably-Achievable doses. Modern radiographic techniques and digital sensors, as well as new film products, ensure that this is possible. It is in the best interest of our patients that we strive to reduce the dental radiation that they accumulate over their lifetimes.

In today’s dental practice, one should only use a well-designed x-ray machine where the time exposure controls are electronic and thus accurately deliver the proper exposure to patients. In most states, these are the only types of controls that pass inspection. If you are not using a machine that uses electronic controls, then replace it as soon as possible.

X-RAY GEOMETRY

|

|

|

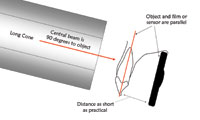

Figure 1. The paralleling concept. |

Figure 2. The sensor holder assembly. |

Along with accuracy of exposure, there are 5 basic rules of the “geometry” of dental intraoral x-rays that the operator should fully understand and follow at all times (Figure 1):

- The source of radiation should come from a point source. This is not controllable by the operator, but rather by the x-ray machine manufacturer, and again gets back to the point that one should only use modern equipment.

- The source-to-object distance should be as long as is practical (the object being the tooth; in this case long cone versus short cone).

- The object-to-film distance, or object-to-digital sensor distance, should be as short as is practical.

- The object (tooth or teeth) and the film or the digital sensor should be parallel.

- The central beam should be 90° to the object as well as the film or the face of the digital sensor.

By taking radiographs following the above 5 rules, we can be sure that the image shown on the film or on the computer screen will be accurate in its shape and size.

There are many devices to help the operator achieve the proper “geometry.” Utilizing XCP or paralleling devices first developed by the RINN Corporation (now DENTSPLY RINN) have stood the test of time in usefulness. Most digital x-ray systems have wisely styled their own holders after the RINN products, allowing the operator to transition quickly from film to digital (Figure 2).

FILM AND SENSORS

Film Selection

The next important factor of imaging is the use of the proper film speed. Several film speeds are available to dentists, the most recent of which are extremely fast. These high-speed films can render good image quality and require minimal exposure.

Digital Sensors

Digital sensors can be much more sensitive to radiation and, therefore, compared to D and E speed film can require much less radiation to yield good image quality. The actual percent of lowered radiation would depend on the age and overall total use of your existing x-ray machines and what type of film you currently use.

Positioning

The operator can use the very best in technology and use great care in the selection of radiation dosage, but the image can still be poor if the patient and the film or sensor are not properly placed.

Patient Positioning

The patient should be seated upright with his or her head in a straight position.

The arch in which you plan to take your image should be parallel to the floor. This means that the operator must take the time and care to reposition the patient’s head when moving from the mandible to the maxilla.

Intraoral Positioning

|

|

|

Figure 3. Anterior film. |

Figure 4. Anterior film. |

|

|

|

Figure 5. Mandibular bicuspid exposure. |

Figure 6. Maxillary molar esposure. |

|

|

|

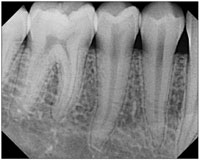

Figure 7. Bicuspid bite-wing film. |

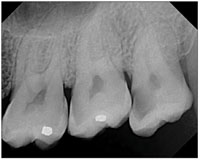

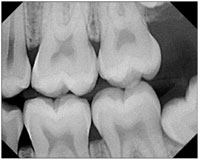

Figure 8. Molar bite-wing film. |

In the case of a full-mouth series, there should be no less than 4 exposures to cover the teeth in each quadrant. Some practices routinely use a higher number of exposures in the anterior region. This is based on the prescribing dentist’s needs. This means that if presented with a patient who has longer than average arch length, or one with overlapping teeth, the operator should take the proper number of exposures that yield sufficient diagnostic information, even if it is more than the traditional number.

Please note that the film or sensor is not adjacent to the tooth or teeth to ensure parallelism. Using the long cone technique provides us the luxury of aligning the film or sensor at a greater distance from the object (the teeth) while still obtaining an accurate image. Placing the film or sensor in this way, in the deeper areas of the mouth, also happens to coincide with patient comfort.

It is advisable that the operator start with the anterior exposures first since this area is the least sensitive part of the oral cavity. Capture these exposures:

- Central-lateral exposure (Figure 3).

- Canine exposure (open the embrasure between the lateral and canine; Figure 4).

- Bicuspid or premolar exposure (ensure that the distal of the canine is imaged; Figure 5).

- Molar exposure (should include all 3 molars or at least all 3 molar areas; Figure 6).

- Bicuspid or premolar bite-wing exposure (should include the distal of both canines; Figure 7).

- Molar bite-wing exposure (Figure 8).

“TROUBLE” SPOTS

In my years of teaching radiographic techniques, the most requests from my students are for guidance on the exposure of canines and molars. It’s true that these are the 2 most difficult areas to image in the whole oral cavity.

Canine Exposure

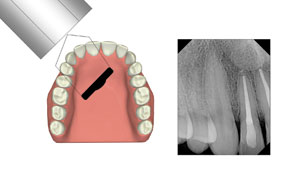

|

|

Figure 9. Cuspid positioning. |

To gain the most useful image of a canine tooth, the operator must ensure that the mesial of the canine is separated from the lateral incisor, or that the central beam goes through the embrasure between the canine and lateral (Figure 9).

Molar Exposure

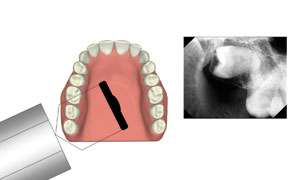

|

|

Figure 10. Distal molar positioning. |

Molar x-rays should include all 3 molars, or at least all 3 molar areas. On the distal molar exposure, the central beam should come from a distal position to ensure the inclusion of the distally hidden anatomical landmarks (Figure 10).

Bending Film

There are many times when one cannot achieve complete parallel placement, and the operator may be tempted to bend the film. This is an unacceptable step, as it will distort the final image. This is not even an option when using digital sensors since they don’t bend. In addition, although it is widely used by many clinicians, the bisection of angle technique can also produce an undesirable image as it distorts the crown-root ratio.

RESPONSIBILITY

As dentists, we have a great responsibility to patients. We also have a responsibility to our team members to help them acquire the knowledge to be the best in their fields. Making the commitment to learning, understanding, and practicing good intraoral radiographic technique helps us meet our goals toward responsible dentistry.

Dr. Schiff has served as professor and chair of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology and Emergency Services, as well as the director of clinical research, at the University of the Pacific School of Dentistry in San Francisco. During his tenure, he became the first-named endowed professor. Dr. Schiff has been recognized worldwide for his contributions to dentistry and radiology, and has received many honors and awards for his outstanding work in both of these fields. He is a fellow of the American College of Dentists, the International College of Dentists, the International Association of Dental Maxillofacial Radiology, and the Pierre Fauchard Academy. He is also a diplomate of the American Academy of Oral Medicine. He can be reached at (415) 789-0060 or thomasschiff@comcast.net.