John A. Molinari, PhD, discusses the past, present, and future of infection control precautions.

Wouldn’t it be interesting to observe how a dentist, a hygienist, and an assistant from a circa-1980 practice would react if they were transported in a time machine into a 2019 dental practice? Chances are they would be very surprised by the additional precautions and procedures that today’s dental professionals perform on a daily basis. The following discussion will attempt to briefly review a few of the changes they might notice.

Personal Protection

Personal Protection

The first and most obvious difference they would see is the use of gloves, face masks, and protective eyewear worn by everyone treating patients. Using gloves as the example here, the majority of dental team members started wearing gloves for patient care in the mid-1980s. However, what some do not realize is that the ADA first approached this topic in a 1976 article published in The Journal of the American Dental Association. It was aimed at protecting dental healthcare providers from what still is the most infectious bloodborne occupational pathogen, the hepatitis B virus. What our colleagues didn’t realize then was that they would adapt and change from “wet-finger dentistry” to “barrier-protected dentistry” within a short time and be safer for it.

Asepsis and Instrument Processing

As the time travelers look into today’s clinical operatories, they also find instruments in pouches or cassettes on bracket trays ready for patient care; wrapped, sterilized instruments stored in designated cabinet drawers; and fewer loose items on counter surfaces. As surprising as these changes appear to them, another surprise comes when they enter the area where contaminated instruments are reprocessed for patient care. They note the absence of the familiar glutaraldehyde sterilization container where they “cold sterilize” a number of items in their practices. Instead, the dental team from the past now sees a designated instrument reprocessing area, where the overwhelming majority of treatment items are heat sterilized, and that other heat-labile items are replaced with single-use disposables. In the practice world of 40 years ago, contaminated instruments were often cleaned manually with a scrub brush. Accidental sharps exposures were not uncommon during these procedures, and post-exposure treatment often stopped after washing hands. Incidents such as these were also only infrequently reported for follow up. Although ultrasonic cleaners designed for the mechanical removal of debris were found in most dental practices, a number of dental personnel still relied on hand scrubbing as the “final” cleaning step prior to sterilization. Ultrasonic units were not periodically checked to determine whether they were functioning properly or not. Also, ultrasonic cleaning solutions may have only been changed weekly or, as one descriptor stated, “when the unit solution became cloudy after use.” Now they learn that the solutions used to clean contaminated items are changed at least daily and the cleaning efficiency of the equipment is periodically monitored using aluminum foil or commercial test strips impregnated with artificial organic soil.

They see that the risky procedure of hand scrubbing instruments is rarely used and, in fact, has now been replaced with both a large ultrasonic unit and a built-in piece of equipment that the infection control assistant in charge calls an instrument washer. “Do not confuse this unit with a dishwasher,” she tells them. “Instrument washers are developed, tested, and FDA-approved to clean sensitive medical instruments. They are not to be confused with dishwashers, which are designed to clean dishes and some pots and pans.” The assistant goes on to tell her colleagues how the practice’s autoclaves are monitored weekly using calibrated spore testing, as recommended by the CDC to ensure that equipment is working properly. She even mentions that, within the last year, the practice began using strips called Class 5 integrators to monitor each sterilization cycle. These strips contain a thin tube with chemical ink that reacts to the parameters of temperature, pressure, and time during the sterilization cycle. “They do not take the place of the required, weekly biological-spore-test monitoring,” she says, “but we can pick up sterilization-cycle failures much more rapidly and correct problems by using these integrators as an adjunct to our biological monitoring system.”

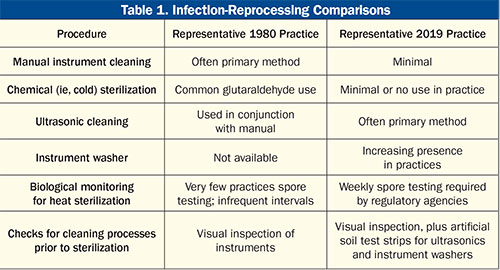

After they return to their own time, the 1980 dental care providers compare notes and realize that they have glimpsed into the future of infection control. They even compile a list of differences to compare what they are used to doing to what 21st-century dental practices routinely perform (Table 1). Today’s dental professionals take many of these for granted, but it can be very helpful to remember that you must remember where you came from in order to know where you are as you prepare for the future.

Dr. Molinari earned a PhD in Microbiology from the University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine and is currently professor emeritus at the University of Detroit Mercy, where he had served as professor and chairman of the Department of Biomedical Sciences and as director of infection control. He was also the infection control director for DENTAL ADVISOR from 2009 to 2018. He can be reached at johnmolinariphd@gmail.com.