INTRODUCTION

When I opened my Philadelphia dental practice in 2011, one of the first pieces of equipment I purchased was a cone-beam unit, described below. Recently, it detected a serious, life-changing abnormality in a patient, something a standard panoramic x-ray would not have been able to find.

CASE REPORT

Not a Routine New Patient Appointment

A few months ago, a new patient in her early 20s visited my office for a routine hygiene appointment. She reported no oral discomfort or pre-existing health conditions.

During the examination, it was noted that the patient had been under orthodontic treatment for an extended period—potentially too long. Visible signs of extensive root resorption were present, particularly in teeth Nos. 2 and 3, which were mobile.

The 2D radiographs also indicated periodontal disease. Based on this preliminary evaluation, both teeth appeared to be potential candidates for extraction and implant placement (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Standard panoramic radiograph of teeth Nos. 2 and 3.

Although it’s unusual for patients in their twenties to lose teeth to periodontal disease, it can happen. The disease and its related bone loss are typically painless as they progress, often leaving the patient unaware for years.

However, when probing the areas around teeth Nos. 2 and 3, there was no resistance, and there appeared to be a 10-mm pocket. To determine the exact nature of the issue, the hygienist took immediate CBCT images of the patient.

An Unexpected Discovery

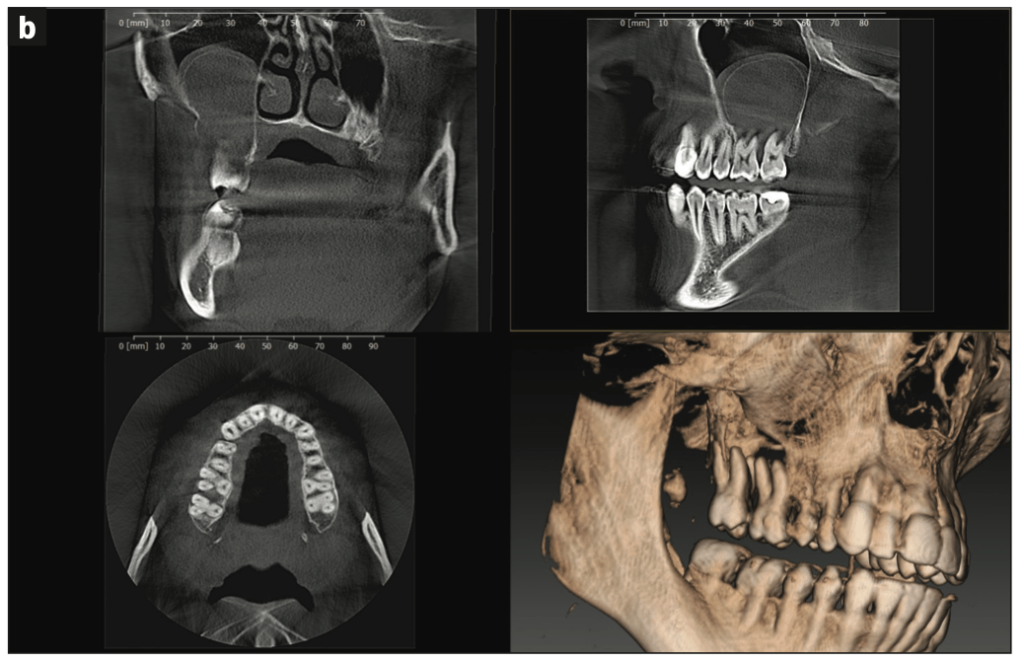

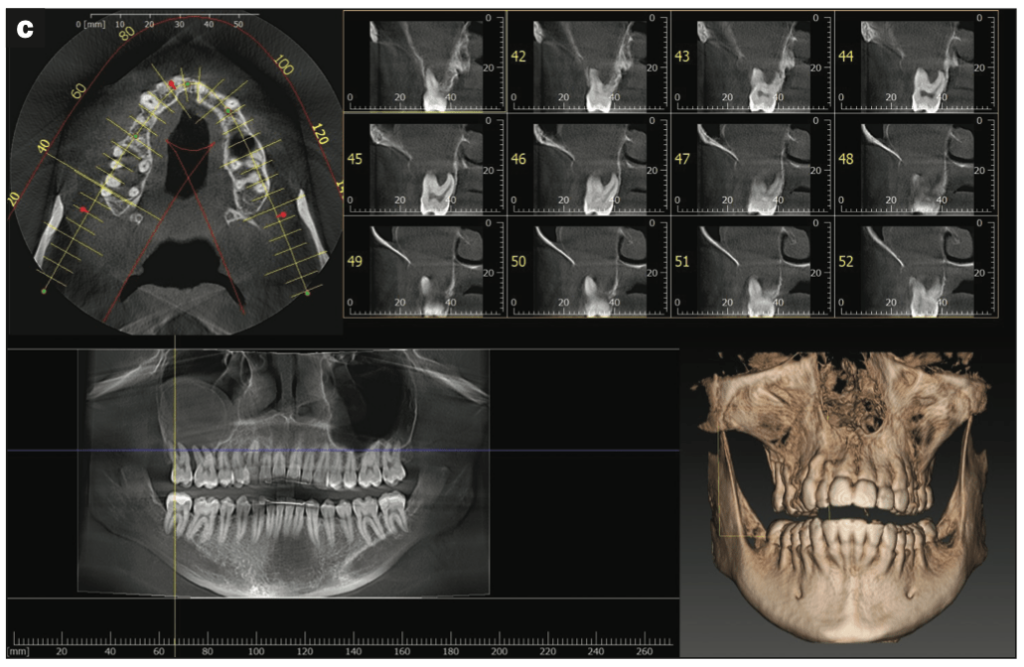

Within seconds, the CBCT radiographs were on my monitor, revealing that this case was far from routine. The 3D radiographs showed a very large mass, about 1 inch in diameter, above teeth Nos. 2 and 3, entering the sinus with no bone surrounding it. Diagnosing this mass was beyond a general dentist’s scope of practice. Moreover, if these teeth were simply extracted, there would be a 19-mm oral/antral communication between the sinus and the mouth. The CBCT scans were essential in preventing a disaster (Figure 2).

Figure 2a.

Figure 2b.

Figure 2c.—Figure 2. CBCT radiographs (I-MAX 3D [Owandy Radiology]) of teeth Nos. 2 and 3.

The patient was understandably devastated. She came into the office for a routine cleaning and dramatically changed her life. Fortunately, the biopsies performed at the hospital concluded that the golf ball-sized mass was not malignant. However, it was determined to be a fast-growing, locally aggressive granuloma of the sinus, which the hospital’s surgeons successfully removed.

A Long Road Ahead

As of this writing, I do not have a definitive prognosis from the hospital surgeons and ENT specialists. The patient is just beginning the early stages of sinus reconstruction, which will require multiple surgeries and bone grafts to close the hole between her sinus and oral cavity.

The bone grafting required cannot be performed with the bone matrix commonly used in implant dentistry. Hospital surgeons will most likely have to take bone tissue from her ribs or hip. Ultimately, the patient will probably be unable to have traditional implants placed. One option being considered is a zygomatic implant-based reconstruction.2

Even if zygomatic implants are a viable option, it will be many months—perhaps years—before this or any routine cosmetic procedure can be performed. The patient’s overall health and full recovery are of the utmost importance.

CONCLUSION

There is a silver lining in this complex and urgent case: detecting this large mass in a very young patient now, rather than 10 to 20 years from now, when it could have become inoperable and could also have resulted in a potential practice-crippling failure-to-diagnose lawsuit.

Cone-beam units are an essential part of today’s diagnostic tools. There are many in the marketplace, and for my practice, I chose the wall-mounted I-MAX 3D from Owandy Radiology. With its small footprint and a 9- × 12-in field of view, this unit proved invaluable for routine implant cases. Having a CBCT scanner in the office not only makes implant placement outcomes more predictable, but it also helps one to be prepared for the unpredictable—and dentistry can often be unpredictable.

REFERENCES

- The American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. The use of cone-beam computed tomography in dentistry: An advisory statement from the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143(8):899-902. doi: 0.14219/jada.archive.2012.0295

- Aparicio C, Ouazzani W, Hatano N. The use of zygomatic implants for prosthetic rehabilitation of the severely resorbed maxilla. Periodontol 2000. 2008;47:162–71. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0757.2008.00259.x

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Gelbart is the owner of Independence Dental Group, a general and cosmetic dentistry practice in downtown Philadelphia. He can be contacted at stevengelbart@idgpa.com.

Disclosure: Dr. Gelbart reports no disclosures.