Plant phytolith and water content cause differing degrees of tooth enamel abrasion in vertebrates, according to an international team of researchers who say that their findings have implications for how tooth wear in extinct animals is interpreted and how this information can be employed to reconstruct their dietary behavior and habitats.

Tooth enamel is abraded more rapidly when plants with a higher phytolith content such as grass are consumed rather than those with a low phytolith content such as alfalfa. Phytoliths are microscopic mineral inclusions made of silica dioxide that are present in many plants.

Although phytoliths are softer than enamel, scientists have been uncertain whether tooth abrasion is mainly caused by phytoliths within the plants or mineral particles and sand adhering to the surface of the plants.

To evaluate the abrasive effect of phytoliths, six groups of guinea pigs were fed for three weeks with three different fresh or dried plants—alfalfa, grass, and bamboo—with varying levels of phytolith content ranging from 0.5% to 3% but otherwise lacking any adhering particles.

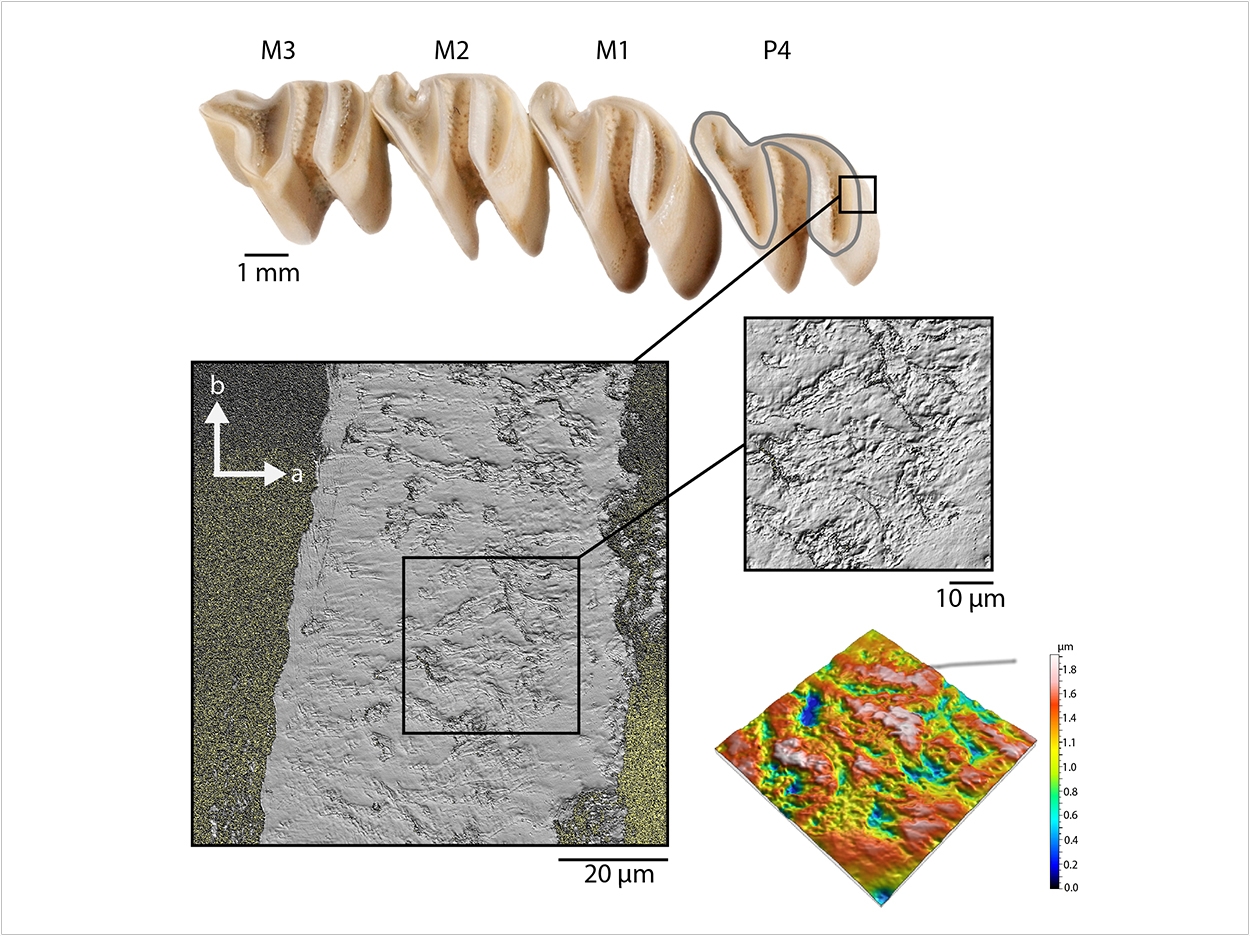

High-resolution microscopy revealed that abrasion on the surface topography of the enamel of the guinea pigs’ molars was more extensive with increasing phytolith content of the feed.

The plants’ water content also played a role, as the researchers systematically analyzed the abrasive properties of fresh and dry plants with different phytolith contents and determined that dry feed results in greater tooth wear than the equivalent fresh feed.

“The enamel of the guinea pigs we had fed on dry grass was much more worn and rougher than the enamel of the animals that had been given fresh, moister grass,” said Dr. Daniela Winkler, head of the study at the Institute of Geosciences at Mainz University.

There were no differences in tooth surface texture in the case of guinea pigs that had eaten fresh or dried alfalfa and those that had eaten fresh grass.

“While there is a similarly low level of wear following consumption of alfalfa and damp grass, the landscapes in which alfalfa or grass grow can differ greatly. This may indicate a potential source of error in how paleontologists have been using tooth abrasion to reconstruct herbivore diets and habitats,” Winkler said.

“We often try to deduce what the habitats of the corresponding animals were like by analyzing the abrasion of their fossilized teeth. Less abrasion, for instance, indicates that the animal might have lived in a wooded landscape with lots of herbage and foliage rather than in a steppe-like environment dominated by grasses,” Winkler said.

“Furthermore, the surface textures of teeth of fresh grass grazers may resemble those of leaf eaters. We need to bear these findings in mind when reconstructing the diet of extinct animals on the basis of their fossil teeth,” Winkler said.

The study, “Forge Silica and Water Content Control Dental Surface Texture in Guinea Pigs and Provide Implications for Dietary Reconstruction,” was published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

Related Articles

Charcoal Toothpaste May Wear Down Enamel

Neanderthal Tartar Reveals Limited Plant-Based Diet

NYU Gets Grant to Study Enamel Formation