INTRODUCTION

Throughout the United States, there remains a population of patients who suffered greatly during the Holocaust, and because of the trauma these survivors endured, certain scenarios, like receiving medical treatment, can trigger fear and prevent receiving care. A white coat, for instance, could remind survivors of forced medical experiments. A loud noise, a crowded clinic, or a small examination room can also be triggers.

Rutgers School of Dental Medicine (RSDM) has a special program called the Holocaust Survivors Program (HSP). Established in November 2020, the HSP offers complimentary dental care to survivors of the Holocaust and is led by licensed dentists and board-certified specialists, who will assign Holocaust survivors to either a DMD candidate or graduate specialty postdoctoral candidates, depending on the complexity of the case. In both clinics, candidates and/or residents are supervised by licensed dentists. Presently, the program has treated more than 85 patients and administered more than 1,000 treatment visits.

To deliver the best care to Holocaust survivors, RSDM began implementing a training program called person-centered trauma informed (PCTI) care to prepare its students to deliver the proper care for Holocaust survivors and all patients who might have experienced trauma. The trauma Holocaust survivors experienced in their early years can have considerable effects in old age. This knowledge is pivotal in guiding the utilization of tools such as PCTI to better equip students in providing effective treatment for these patients.1

PCTI is an underutilized concept that has gained recognition in recent years for its profound impact on healthcare outcomes. While the healthcare community often emphasizes understanding a patient’s medical history and current medications, PCTI delves deeper into comprehending potential barriers resulting from past traumas.2

Moreover, PCTI considers the providers’ medical responsibility to proactively and thoroughly understand the potential barriers patients may have as a result of traumas sustained. PCTI includes understanding the possible negative experiences, the trauma, and the stressors a patient may be dealing with and how to avoid specific triggers that may impact the patient’s desire to pursue and follow through with care. It demands that the patient be the central focus of the care while being treated with dignity and respect holistically.3

RSDM has taken a pioneering step by incorporating PCTI training into its curriculum and patient services. In this article, we explore how RSDM utilizes PCTI training to address the unique needs of survivors and provide comprehensive dental care.

Material

The PCTI training provides background on the Holocaust and its impact on the survivors; it also equips participants to recognize trauma and treat patients accordingly. As part of their mandatory selective/electives, all third- and fourth-year DMD candidates take an online certificate course offered by The Blue Card, a nonprofit organization dedicated to caring for Holocaust survivors. Postdoctoral candidates and residents, as well as faculty and staff members partaking in HSP, can also take the online course, obtain a certificate, and receive continuing education credits. The school has made Holocaust survivor PCTI training mandatory for all clinical students and residents.

As part of the training, students learn about the unique challenges Holocaust survivors often face that hinder their ability to seek dental care. These challenges include the cost of dental care, transportation issues, fear of the dental setting, and a reluctance to bother the dentist. Many survivors have postponed or given up on seeking treatment, resulting in ill-fitting dentures and other dental issues that significantly impact their daily lives.

Results

While providing care to the Holocaust survivors at RSDM, several recurring themes or chief complaints emerged, such as:

- “I can’t eat or smile.”

- “I’m embarrassed at how I look.”

- “My denture is loose and makes me gag, making it difficult to eat or speak.”

Ill-fitting, loose removable dentures and iatrogenic dentistry were noted in many of the HSP patients. These conditions led to loss of function, such as the ability to chew and digest food and the ability to speak properly. An increased “gag reflex” was noted in several patients. Some indicated that dental care is primarily for the younger generation or that they “didn’t want to bother the dentist.”4 As a result, many suffered needlessly with the loss of function and poor aesthetics. The loss of natural teeth and subsequent bone loss and the loss of vertical dimension of occlusion led to impairment, disability, and handicaps in the HSP population.5

Poor aesthetics were noted in many patients. These patients expressed embarrassment with their appearance due to their teeth and a reluctance to smile. These dental problems can exacerbate social isolation, especially in the elderly population; many were withdrawing from everyday activities. This can lead to broader social effects, particularly isolation from other people. Traumatic life events may influence the elderly’s ability or desire to seek dental care.6 Certainly, the early life experiences of the Holocaust survivors were emotionally and psychologically damaging. Many of the Holocaust survivor patients recounted their stories of the Holocaust with the providers, the dental navigator, and the faculty. Current life and world events may also affect the HSP patient’s attitudes; many also suffer from compromised medical health.

The restoration of proper function, aesthetics, and occlusion was the goal in treating the HSP patients at RSDM. In many instances, ill-fitting removable dentures were replaced with fixed dentures, either via natural teeth or an implant-supported, fixed bridge. When deemed necessary, removable dentures with implant-supported LOCATOR attachments were used.

The transition from a loose, removable denture to fixed, implant-supported dentures can be life-changing. Patients reported that they were better able to chew their food and felt more confident knowing that their dentures would not fall out. Many felt improved “biting force.”7 The re-establishment of occlusion also improved function and, in some cases, aesthetics. Advanced cosmetic dentistry techniques enhance the patient’s smile via tooth whitening, crowns, and veneers.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 90-year-old male patient presented to the HSP with the chief complaint, “My upper teeth broke, and I can’t eat or smile. I tried to repair the teeth with glue, but I could not afford to return to my dentist. I am embarrassed to smile or talk in public or around my family and friends.”

The patient presented with a complicated medical history, including hypertension and a recent stroke. He had limited movement in one arm and his legs.

Clinical and radiographic exams revealed fractured maxillary anterior teeth with no posterior right occlusion except for the maxillary second premolar (Figure 1a). The maxillary right cuspid was horizontally impacted. Treatment options did not include extraction of the cuspid due to the extent and possible morbidity of the procedure. Treatment included implants in area of Nos. 3 and 5, with RCT and post and core at No. 8, crown preparation at No. 4, and placement of a fixed bridge on implants and teeth Nos. 3 to 5, X, X, 8, and 9 (“X” denotes a pontic). To prevent caries on the natural teeth, telescopic copings were permanently cemented on all natural teeth, with custom abutments on Nos. 3 and 5 (Figure 1b).

The patient was restored to sound function and aesthetics. His self-confidence also came back, and he was comfortable speaking, masticating, and smiling (Figure 1c).

Case 2

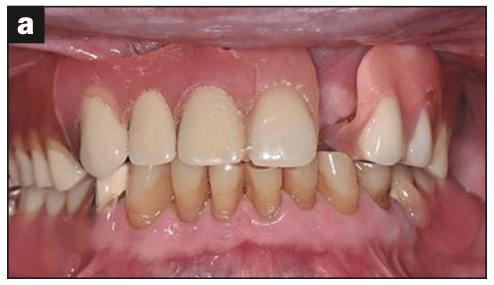

An 84-year-old patient presented to the HSP with the chief complaint, “I have a tight feeling in my upper right and left back areas, with bleeding, and I do not like the spacing of my front teeth. I am very embarrassed about how I look.” The examination revealed moderate periodontitis in these areas (Figure 2a). Therapy included scaling and root planing throughout, with osseous surgery in the maxillary right area. Two abutments in the maxillary left area required root canal therapy and post and cores. Her anterior teeth were prepared for crowns to close her diastemas after she accepted a diagnostic wax-up and a digital prototype. New restorations were placed from the maxillary right cuspid No. 6 through No. 15 (the maxillary left second molar) (Figure 2b). The case resulted in proper function, aesthetics, and occlusion. The patient had immediate improvement in self-esteem and confidence.

Case 3

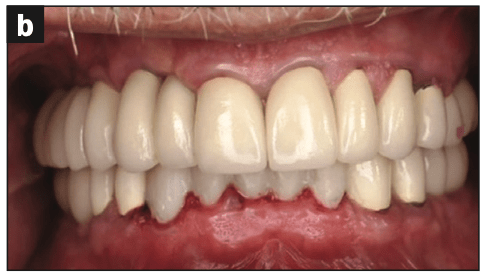

An 85-year-old presented to the HSP with the chief complaint, “I am embarrassed about how my teeth look, and I cannot function well.” Medical history revealed a heart condition that necessitated a cardiology consultation for stopping blood thinners before surgical procedures. The examination revealed broken restorations, severe caries, loss of vertical dimension, and improper occlusion (Figure 3a).

His treatment plan was a full-mouth rehabilitation that included therapy from the periodontics, endo-dontics, and prosthetic departments. Many teeth were saved with root canal therapy and crown-lengthening surgery, while several teeth were extracted and had implants placed in these areas as well as edentulous areas.

The patient was restored to proper function and aesthetics (Figure 3b). This allowed for proper mastication and gave him the appearance to function in society.

Case 4

An 87-year-old presented to the HSP with the chief complaint, “My top denture is loose and makes me gag. I cannot chew with my lower denture; it is loose, and it moves when I eat or talk. I am embarrassed in front of people.” The patient had a medical history that included a previous heart attack and acid reflux disease. Consultation with his cardiologist allowed us to stop his blood thinners prior to surgery. Clinical and radiographic examination revealed a low lip line and combination syndrome (Figure 4a).8,9

Therapy consisted of restoring the occlusion and vertical dimension. The mandibular remaining teeth were all crowned, and posterior implants were placed in the mandible. In the maxilla, an implant-supported overdenture was made. Five fixtures allowed for a “horseshoe-shaped” prosthesis to prevent gagging and allow for proper function and aesthetics (Figure 4b).

The patient was restored to proper function with quality aesthetics, giving him comfort, self-confidence, and self-esteem (Figure 4c).

DISCUSSION

PCTI principles are paramount in the treatment planning process. The dental care provided is more important than providing routine or complex treatments; it becomes a transformative experience that goes beyond traditional health care. In cases presented at RSDM, providers worked collaboratively, employing interdisciplinary care and communication between different specialties. The principles of PCTI were integrated into the treatment planning process, ensuring that patients actively participated in decisions about their care.

One patient commented, “I have never had a say in determining my treatment. The dentist just told me what to do.” The empowerment to be part of the decision-making process instilled confidence in the HSP patients.

The use of a “dental navigator,” who facilitated scheduling, transportation, and overall orientation, was part of the “VIP” treatment offered to these patients. The collaborative approach of student doctors and faculty provided comprehensive dental care to a population that could otherwise be underserved.

It was also noted among the HSP patients treated that the interaction with the young student doctors also had a positive effect on their overall attitude toward dental treatment. HSP patients stated that they “looked forward” to their dental visits.

The patients’ chief complaints regarding function, aesthetics, and the cost of dentistry were addressed. The HSP not only dealt with the dental issues but also positively impacted the mental health of survivors. Restoring their smiles and confidence played a significant role in combating isolation and improving overall quality of life. A confident smile contributes to positive self-perception, vitality, and youthfulness. For elderly Holocaust survivors, the newfound confidence achieved through the HSP allowed them to engage more actively in their communities, fostering stronger family bonds and empowering them to be socially active.

The results of the HSP at RSDM were significant, with patients reporting improved function, confidence, and satisfaction. The transition from loose removable dentures to fixed, implant-supported dentures was life-changing for many survivors. The interdisciplinary care delivered by student doctors, faculty, and specialists ensured that the patients’ chief complaints were effectively addressed.

CONCLUSION

At RSDM, the HSP has provided a safe and transparent environment in which to treat survivors using PCTI principles. The HSP not only addressed dental issues but also positively impacted the mental health of survivors. Restoring their smiles and confidence played a significant role in combating isolation and improving overall quality of life. Both routine and complex treatment have been provided to Holocaust survivors. The use of PCTI in other cohorts should be considered among populations such as veterans, survivors of domestic abuse, or any group that has suffered trauma and isolation.10

The institution’s HSP exemplifies the transformative power of PCTI in dental treatment. By understanding the unique needs and challenges faced by Holocaust survivors, incorporating interdisciplinary care, and prioritizing effective communication, the program has not only addressed oral health issues but has also contributed to the overall empowerment and reintegration of survivors into society. The cases presented showcase the profound impact of PCTI on restoring function, aesthetics, and self-esteem, ultimately providing a renewed sense of confidence and well-being for Holocaust survivors. As dental care providers continue to embrace PCTI principles, the potential for positive change in patient outcomes becomes limitless, revolutionizing the landscape of health care for trauma-affected populations.

REFERENCES

- Greenblatt-Kimron L, Cohen M. The role of cognitive processing in the relationship of posttraumatic stress symptoms and depression among older Holocaust survivors: a moderated-mediation model. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2020;33(1):59-74. doi:10.1080/10615806.2019.1669787

- Jackson ML, Jewell VD. Educational practices for providers of trauma-informed care: A scoping review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2021;60:130–8. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2021.04.029

- Cannon LM, Coolidge EM, LeGierse J, et al. Trauma-informed education: Creating and pilot testing a nursing curriculum on trauma-informed care. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;85:104256.

- Mojon P, MacEntee MI. Discrepancy between need for prosthodontic treatment and complaints in an elderly edentulous population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1992;20(1):48-52. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.1992.tb00673.x

- Monacis L, Muzio LL, Di Nuovo S, et al. Exploring the mediating role of oral health between personality traits and the psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics among healthy older people. Ageing Int. 2020;45(1):18-29. doi:10.1007/s12126-019-09358-6

- Allen PF, McMillan AS. A review of the functional and psychosocial outcomes of edentulousness treated with complete replacement dentures. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69(10):662. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104256

- Lindquist LW, Carlsson GE, Hedegård B. Changes in bite force and chewing efficiency after denture treatment in edentulous patients with denture adaptation difficulties. J Oral Rehabil. 1986;13(1):21–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2842.1986.tb01552.x

- Tjan AH, Miller GD, The JG. Some esthetic factors in a smile. J Prosthet Dent. 1984;51(1):24–8. doi:10.1016/s0022-3913(84)80097-9

- Kelly E. Changes caused by a mandibular removable partial denture opposing a maxillary complete denture. J Prosthet Dent. 1972;27(2):140–50. doi:10.1016/0022-3913(72)90190-4

- Raja S, Rajagopalan CF, Kruthoff M, et al. Teaching dental students to interact with survivors of traumatic events: development of a two-day module. J Dent Educ. 2015;79(1):47-55.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Moran is an assistant professor in the Department of Diagnostic Sciences and a group practice administrator in clinical affairs at the Rutgers School of Dental Medicine (RSDM). In addition to being in full-time private practice for 45 years, Dr. Moran worked as a public health dentist in Elizabeth, NJ, treating underserved populations. He currently is the director of the Holocaust Survivor Program at RSDM. He can be reached at jtm213@sdm.rutgers.edu.

Dr. Conte is currently a professor in the Department of Restorative Dentistry and the senior associate dean for the Office of Clinical Affairs at RSDM, where he also serves as the medical director and the director of infection control and environmental safety for the dental school. Additionally, Dr. Conte serves and chairs many committees and is involved in the oversight of the dental school’s programs and facilities administration. Dr. Conte is active in numerous associations, including the ADA and the Organization for Safety, Asepsis and Prevention. He is a Fellow of the AGD, the American College of Dentists, and the International College of Dentists. He is a graduate of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (now known as RSDM) and has completed years of additional postgraduate training, including an Advanced Education in General Dentistry Program and at the American Dental Education Association’s Leadership Institute. He can be reached at contemi@sdm.rutgers.edu.

Ms. Vega is a dental care coordinator at RSDM. She earned her degree in social work from Rutgers University and is currently enrolled in the graduate program at the Rutgers School of Social Work in New Brunswick, NJ, where she is pursuing her master’s in clinical social work. She served as the patient navigator for the Holocaust Survivor Program at RSDM, where she coordinated dental care, ensuring survivors received the dental services they needed and offering emotional support as they navigated their treatments. She can be reached at carolina.vega@rutgers.edu.

Dr. Drew is a professor, the director of implantology, and the vice chairman in the Department of Periodontics at RSDM. He received his doctorate and degree in Periodontics from RSDM. He has been awarded the RSDM Excellence in Teaching Award, Stuart D. Cook Master Educators Guild Award, and the prestigious American Academy or Periodontology Educator Award. Dr. Drew was inducted into the American College of Dentists, and he was awarded the RSDM Alumni Association Decade (1980s) Award. He has written for more than 35 publications and has lectured throughout the country. He was in full-time clinical practice for more than 25 years. He can be reached at drewhj@sdm.rutgers.edu.

Disclosure: The authors report no disclosures.