The void in physicians’ and nurses’ knowledge of diseases and conditions of the oral cavity may be attributed to the 19th century schism that has historically divided medicine and dentistry. However, some have speculated that dentistry was set apart from medicine in 1840 when Horace Hayden and Chapin Harris established the world’s first dental school (Baltimore College of Dental Surgery), and originated the doctor of dental surgery degree.1 Regardless of when, or how, the study of the oral cavity became separated from the study of other organ systems, non-dental healthcare providers (HCPs) have generally considered oral health the domain of dentists and dental hygienists.

This historical schism is now changing. The growing body of evidence of the interrelationships between oral and overall health is a knowledge base that can no longer be ignored. Healthcare and education authorities have taken the position that educating physicians and other non-dental HCPs about oral-systemic health can no longer be considered optional.

|

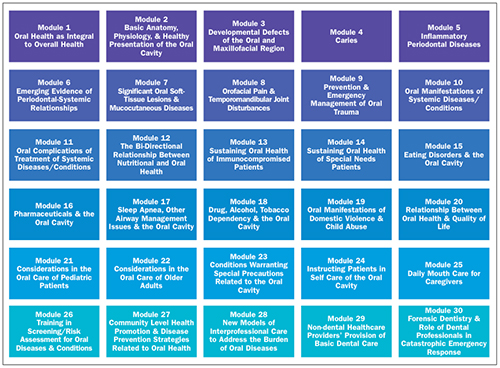

| Figure 1. Overview of the courses contained in the curriculum, Oral-Systemic Health Education for Non-Dental Healthcare Providers, under development at the University of Manitoba. |

IMPERATIVES TO REPAIR THE VOID

It has been more than a decade since the landmark report, Oral Health in America (OHA),1 was published. The report’s findings brought to the forefront the need to address access to dental care in underserved populations and the endorsement of medical-dental collaboration “to provide optimal health care for…patients.” To make these changes in healthcare delivery, OHA cited the need to change non-dental HCPs’ perception of the importance of oral health. The report also suggested that, “Too little time is devoted to oral health and disease topics in the education of non-dental health professionals,” and advocated for educational reform providing for curriculum changes and multidisciplinary training in oral health. Of note, this call to action in educational reform was very clear and very well publicized 13 years ago.

About 7 years after the OHA report was issued, the American Dietetic Association published a position paper2 that acknowledged nutrition as an integral component of oral health. Among many other related recommendations, the paper proposed that both didactic and clinical practice concepts that illustrate the role of nutrition in oral health be included in the education of dieticians.

In 2008, another pivotal report, Contemporary Issues in Medicine: Oral Health Education for Medical and Dental Students, Medical School Objectives Project,3 was published. In it, the American Association of Medical Colleges suggested major oral health themes that might be incorporated into an oral health curriculum for physicians. The report also discussed new strategies to better integrate oral and systemic learning objectives and promote interprofessional collaboration.

Oral health-related topics are also being tested on both step 2 clinical knowledge4 (diagnosis of disorders of the mouth, salivary glands, oropharynx, esophagus, and disorders of the salivary glands); and step 3 exams5 of the United States Medical Licensing Examination. A recent investigation of internal medicine trainees’ level of knowledge and orientation of oral health, specifically in regard to periodontal disease and adverse health events, suggests that medical schools should provide more comprehensive training in oral/periodontal health.6

SO WHERE DO WE STAND TODAY?

It seems fairly clear that setting a course to develop a comprehensive curriculum in oral-systemic health for non-dental HCPs has become a very important objective. What was not so clear was the magnitude of the knowledge gap that exists in the undergraduate education of physicians, nurses, and other non-dental HCPs. Equally as important was determining which topics in oral-systemic health are perceived by medicine, nursing, etc, to be the most important.

DEFINING THE KNOWLEDGE GAP

Several years ago, my colleagues and I published the findings7 of an international survey of schools of medicine, nursing, and pharmacy to explore this knowledge gap and ascertain what oral health topics physician, nurse, and pharmacist academics thought were most important to teach. Associate deans from the responding schools strongly endorsed the concept of a curriculum dedicated to oral-systemic health for non-dental healthcare students. Their feedback suggested that the most important topics to be taught are related to the diseases of the oral cavity that are the most prevalent, specifically periodontal disease and caries. The relationship between periodontal disease and systemic diseases such as respiratory diseases and atherosclerosis were also of high priority. According to feedback we received from the deans, the majority of undergraduate students from these 3 disciplines were not being taught to examine the mouth, nor were they instructed on how to perform an oral examination. Obviously, training in how to perform an oral examination must be a high priority.

Yet, despite the call for curriculum reform targeting the inclusion of oral-systemic health for non-dental HCPs, and the realization that the magnitude of the knowledge gap is great, a comprehensive curriculum that is evidence-based, interprofessionally vetted, and authored by subject matter experts, did not exist. Recently, this has changed.

|

MOVING FROM JUST AN IDEA TO CREATING CURRICULA

Late in 2007, the Faculty of Dentistry at the University of Manitoba began the arduous but exciting process of creating a vision and blueprint for a comprehensive, evidence-based, interprofessionally reviewed curriculum about oral-systemic health for physicians, nurses, and other non-dental HCPs. To advance the vision for this important curriculum project, we engaged in numerous activities specifically designed to increase the awareness of the importance of oral health within our own faculties, including medicine, pharmacy, nursing, human nutritional sciences, occupational therapy, speech and language pathology (among others), and various special interest groups.

What people from inside and outside the university began to see was the potential impact of a curriculum in addressing comorbid diseases associated with the oral cavity. People started to see that given the appropriate education and training; physicians, nurses, pharmacists, dieticians, speech pathologists, and other non-dental HCPs could impact the epidemiologic trends in serious and often debilitating oral diseases and conditions.

One of the things that attracted the attention of stakeholders from public health agencies was that a curriculum to educate non-dental HCPs about oral health might help address i

ssues related to access to dental care, especially in underserved populations at risk for inflammatory driven disease states linked to the oral cavity. As we know it today, the public health infrastructure for dental treatment (whether in Canada or the United States) is insufficient to address the needs of many high-risk populations. Non-dental HCPs are well positioned to provide basic oral healthcare in nursing home settings, homeless populations, refugee camps, and low resource countries, in addition to many other oral health services that have been traditionally provided by dentists and dental hygienists.

In the spring of 2009, the planning phase of the curriculum was completed. Guided by an exhaustive review of an interprofessional advisory board, the blueprint for the curriculum went through various iterations over a 14-month time span. The board was comprised of 50 experts internal and external to the University of Manitoba, representing academia, research, and clinical practice, from a wide range of disciplines including dentistry, dental hygiene, pharmacy, dietetics and human nutritional science, nursing, physician assistants, respiratory therapy, medicine, occupational therapy, speech and language pathology, psychology and aging, and community health science and gerontology. Members of the advisory board were asked to review the proposed oral health topics to provide specific feedback about such things as relevancy to non-dental professions, prioritization of oral health topics, accuracy of learning objectives, and defining what tools could be developed to assist physicians in implementing the recommendations for clinical application contained in the courses. The suggestions made by the advisory board were also helpful in defining multimedia formats that would best engage the adult learner. As a result, substantial resources have been dedicated to medical illustration, 3-diminsional animation, videography, and other multimedia components. The course is also available in PDF hard copies. The board was unanimous in recommending that preliminary courses be thoroughly peer reviewed by an interprofessional group before being finalized.

Based on the recommendations of the advisory board, the curriculum was expanded to 30 individual courses, each about one hour in length (Figure 1). Taken as a whole, these courses constitute the first, comprehensive curriculum on oral-systemic health for physicians and other non-dental HCPs which is evidence-based, interprofessionally vetted, and authored by the world’s leading subject matter experts. It has been named Oral-Systemic Health Education for Non-Dental Healthcare Providers. The courses are appropriate for both prelicensure education of students from non-dental healthcare disciplines as well as continuing medical education for practicing professionals from non-dental disciplines.

The first 2 courses of the curriculum have been completed. These are “Empowering Physicians, Nurses, and other Non-Dental Healthcare Providers in the Prevention and Early Detection of Oral and Oropharyngeal Cancer” and “Interprofessional Care of the Oral Cavity of Immunocompromised Patients.” These courses will be released in interactive multimedia versions at oralhealthed.com within the next several months and are free to physicians. Those who complete the courses will be awarded continuing medical education credit.

There are 3 other courses currently under development. These include “The Importance of Physicians’ and Other Non-Dental Healthcare Providers’ Intervention of Periodontal Disease,” “Physicians, Nurses, and other Non-Dental Healthcare Providers’ Role in the Oral Care of Older Adults,” and “Physicians, Nurses, and Other Non-Dental Healthcare Providers’ Role in the Oral Care of Children, Adolescents, and Teenagers.” (These are expected to be completed for online delivery for continuing medical education in the latter part of 2013.)

CHAMPIONS OF THE CURRICULUM PROJECT

One of the reasons that we have been successful in bringing about this innovative curriculum is a very unique set of circumstances at the University of Manitoba. Dr. Tony Iacopino, the dean of the Faculty of Dentistry, has been a long-time (and fervent) advocate for translation of oral-systemic science into models for collaborative care. Therefore, convincing him to help fund a curriculum to educate non-dental HCPs about oral diseases and conditions was easy. As he will say, “You had me at hello.” What made this a perfect scenario was when Dr. Brian Postl became dean of the Faculty of Medicine. Dr. Postl, a highly respected Canadian pediatrician, has witnessed firsthand the travesties of early childhood decay along with other oral health problems. As a result, he has become a very strong advocate of oral-systemic heath education at all levels, including undergraduate and graduate medicine, in addition to including oral health in continuing medical education. Dr. Jose Francois, the associate dean of continuing professional development in the Faculties of Medicine and Denistry, has also been a tireless advocate, and valuable resource for medical expertise for this project. I have come to realize that without the serious support of a medical school, a curriculum on oral health for physicians will never be implemented. The University of Manitoba will be one of the first in the world to integrate oral health education into medicine.

In 2012, we were fortunate that the provincial health ministers were excited enough about the curriculum project to award a $500,000 grant to support the development of the courses during the next 4 years.

CLOSING COMMENTS

Making a Difference for Dentists and Dental Hygienists

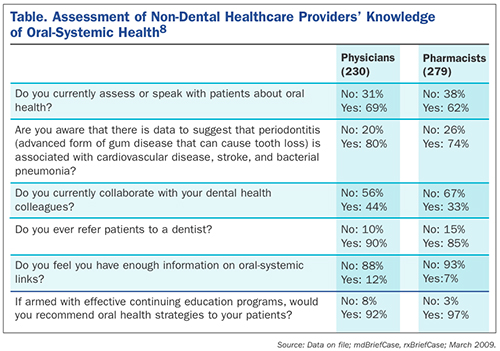

In contemplating whether the courses within Oral-Systemic Health Education for Non-Dental HCPs will make a difference to everyday practitioners in dentistry and dental hygiene, consider the answers that Canadian physicians and pharmacists gave to a recently conducted electronic survey (Table).8 The results showed that 88% of physicians and 92% of pharmacists believe they do not have enough information on oral-systemic interrelationships.

Other responses to this survey indicate that, even though physicians may be aware of periodontal-systemic links and they may refer patients to dentists, the majority do not collaborate with their colleagues in dentistry; that’s the challenge. Gaining knowledge is one thing, but translating it into action is quite another. In order to integrate evidence of oral-systemic science into their clinical practice, physicians will necessarily have to start to look carefully within the oral cavity, and make appropriate referrals to oral HCPs. The corollary is also true. Traditionally, oral HCPs have not considered overall health issues as their responsibility.

To reap the benefits of true medical-dental collaboration, I think most would agree that dentists and dental hygienists must be willing to look beyond the tonsils. This is the intersection where patient outcomes can best be enhanced. And after all, shouldn’t this be the goal?

References

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2000.

- Touger-Decker R, Mobley CC; American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: oral health and nutrition. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1418-1428.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Report IX. Contemporary issues in medicine: oral health education for medical and dental students. Medical School Objectives Project. June 2008. members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/Contemporary%20Issues%20in%20Med%20Oral%20Health%20-Report%20IX.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2013.

- Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States, National Board of Medical Examiners. United States Medical Licensing Examination, 2012-2013. Step 2: Clinical knowledge (CK). Content description and general information. usmle.org/pdfs/step-2-ck/2012—13_FINAL_S2_GSI.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2013.

- Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States, National Board of Medical Examiners. United States Medical Licensing Examination, 2013. Step 3: Content description and general information. usmle.org/pdfs/step-3/2013content_step3.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2013.

- Quijano A, Shah AJ, Schwarcz AI, et al. Knowledge and orientations of internal medicine trainees toward periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2010;81:359-363.

- Hein C, Schönwetter DJ, Iacopino AM. Inclusion of oral-systemic health in predoctoral/undergraduate curricula of pharmacy, nursing, and medical schools around the world: a preliminary study. J Dent Educ. 2011;75:1187-1199.

- mdBriefCase.com, rxBriefCase.com. Assessment of non-dental healthcare providers’ knowledge of oral-systemic health (unpublished data, March 2009).

Ms. Hein holds a bachelor of science degree in dental hygiene from West Virginia University and a master’s of business administration degree from Loyola. She has more than 30 years of experience as in private practice, education, public health, and consulting. She is a member of the American Dental Hygienists’ Association, Colorado Dental Hygienists’ Association, American Association of Diabetes Educators, American Dental Education Association, and the National Speakers’ Association, and serves on the advisory boards of several companies and as an independent consultant to the dental industry. Ms. Hein is an assistant clinical professor in the department of periodontics, and director of education of the International Centre for Oral-Systemic Health, in the Faculty of Dentistry, and an assistant professor in the office of continued professional development, and Director of Interprofessional Development, in the Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba. In these positions, she is developing the first comprehensive, multimedia online curriculum specifically related to oral-systemic health for physicians, nurses, and other non-dental healthcare providers. She also has a dental education company, Casey Hein & Associates, LLC (caseyhein.com) which offers accredited continuing education and other resources focusing on interprofessional collaboration in caring for patients with systemic diseases associated with oral infections and pathologies. Ms. Hein is extensively published and founded the first journal on oral-systemic science, Grand Rounds in Oral-Systemic Medicine. She maintains a busy international speaking schedule, including some of the most prestigious venues where she has been recognized as an innovator in developing models of interprofessional practice that transfer evidence of oral-systemic relationships into everyday patient care. She can be reached at casey@caseyhein.com.

Disclosure: Ms. Hein reports no disclosures.