Reattaching Fractured Segments

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 92% of accidental traumatic injuries commonly affect the anterior region involving the maxillary central incisors (CIs), followed by the lateral incisors (LIs) with coronal fractures due to falls, sport injuries, and vehicle accidents that have been documented in the literature.1-3 Cast or prefabricated posts with cores, pin-retained restorations, and partial- or full-coverage crowns have been the only treatment choices in the past era of dentistry.

Yet their drawback is compromised sound tooth structure that may limit the long-term prognosis of that tooth and the aesthetics with adjacent teeth.4

The adhesive dental era has allowed clinicians to simulate the original dental anatomy, thus rehabilitating function and aesthetics in a short period by preserving tooth structure with the help of new and different restorative materials.5 This article presents a case report on a compound fractured maxillary LI and CI that were successfully treated using endodontic treatment and followed by tooth fragment reattachment in a single visit.

CASE REPORT

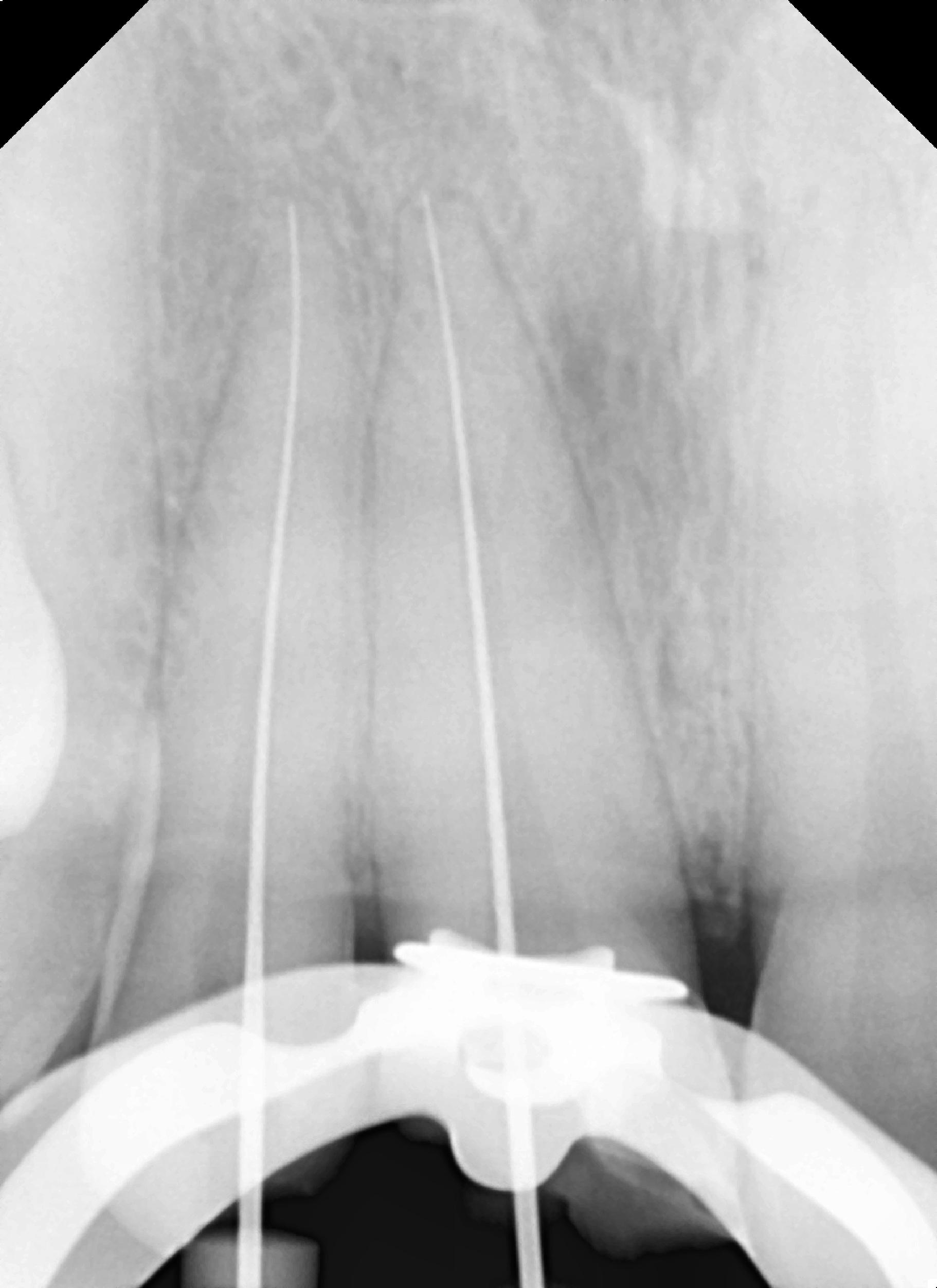

A 31-year-old male patient arrived in the private clinic with a chief complaint of fractured teeth due to a fall to the ground 12 hours prior. The separated tooth fragment was stored in normal saline by the patient and brought to the emergency dental appointment (Figure 1). A periapical radiograph was taken to evaluate the damage to the teeth and adjacent bone (Figure 2). An oral examination revealed an Ellis class III fracture, including an extensive crown fracture, considerable loss of dentin and pulp exposure, a separated right maxillary CI, a fracture line noted on the oblique facial incisal and another on the palatal, and an LI with an oblique fracture (Figure 3).

Figure 1. This is the portion of the coronal of the right maxillary incisor that detached from the tooth following trauma.

Figure 2. A periapical radiograph following the traumatic fracture of the right maxillary lateral and central incisors.

Figure 3. Clinical appearance of the traumatic fracture to the maxillary right lateral and central incisors.

Pulpal exposure was noted on both the lateral and central incisors, and endodontic treatment was recommended, followed by reattachment of the fractured segment on the CI with the restoration of both teeth using a bonded resin. Considering the clinical examination and the patient’s concerns and expectations, a single-visit endodontic strategy was planned that would be followed by a reattachment procedure of the fractured portion of the CI. The portion of the LI that had been fractured off the tooth was not presented by the patient and would be restored with a bonded resin since that missing tooth portion was minor compared to that of the CI.

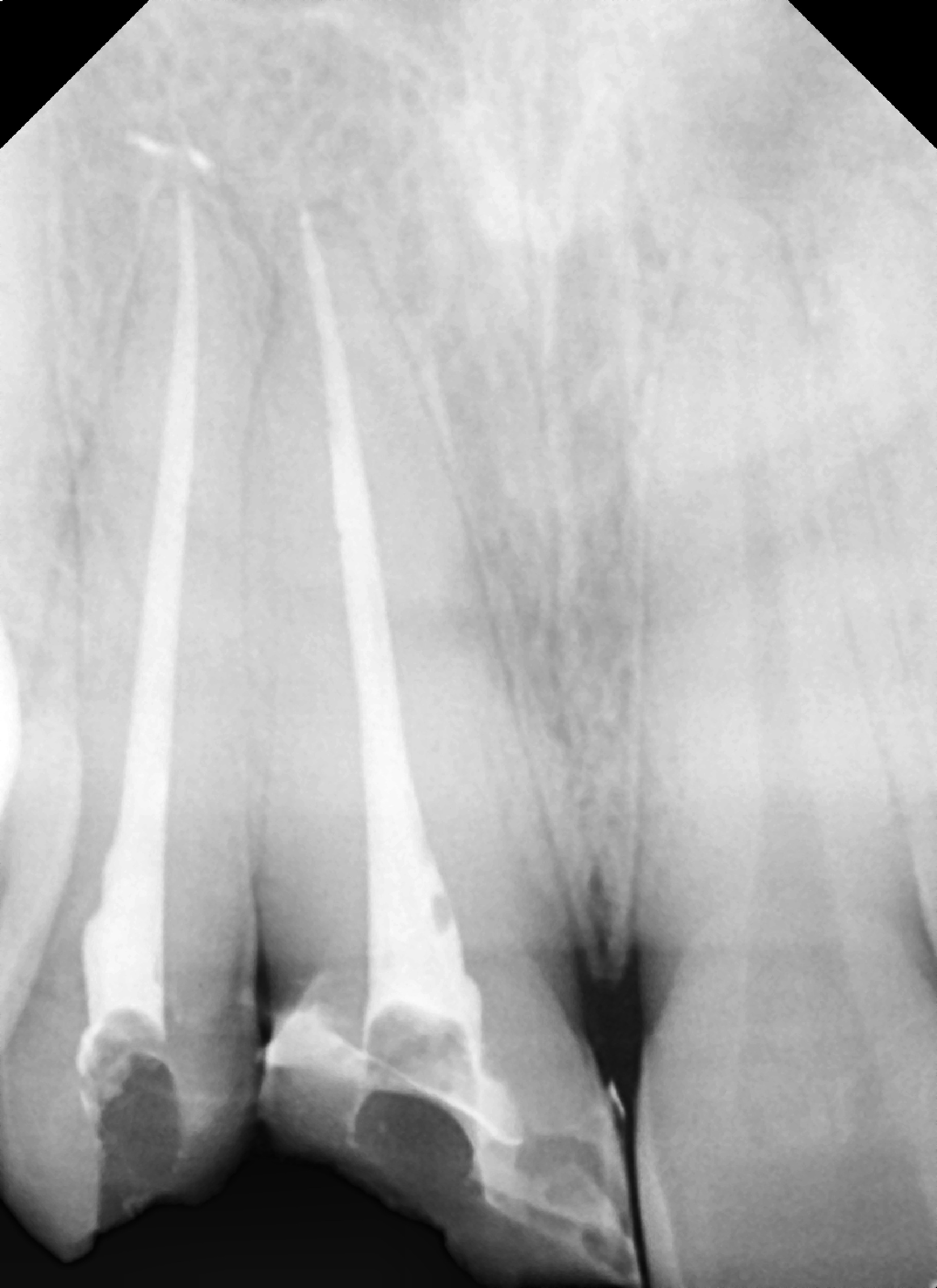

Single-visit endodontics were performed under a rubber dam following an infraorbital nerve block. Access was made into both pulp chambers by enlargement of the pulpal exposure with a conservative approach to tooth structure removal. Working length was set at 24 mm for the LI and 23.5 mm for the CI. A size 15 file was placed into each canal to working length, and a periapical radiograph was taken to verify working length (Figure 4a).

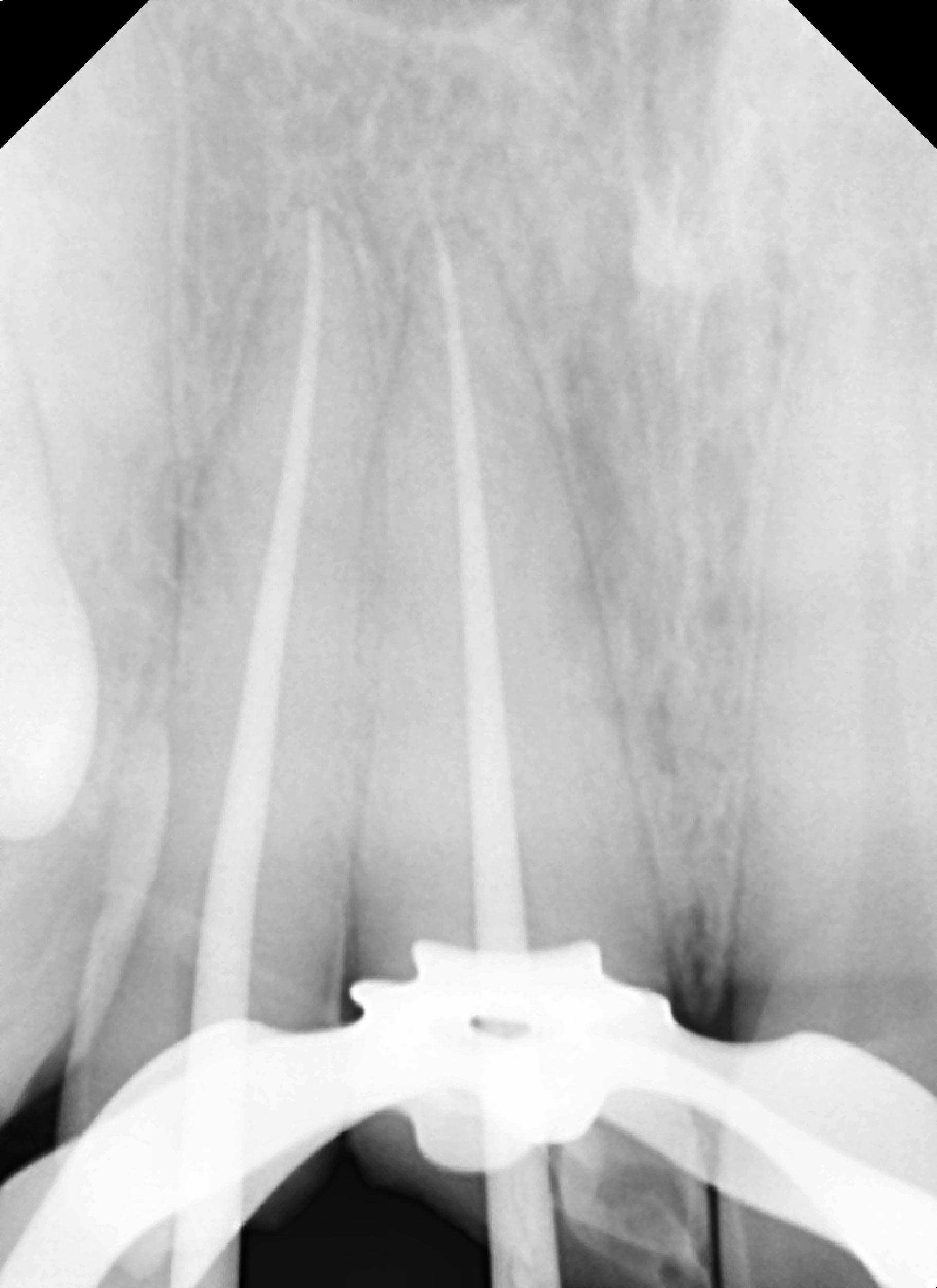

Instrumentation was performed with size 25 files (One Shape [Micro-Mega]) to a size twenty-five 6%, and a gutta-percha cone matching the final file was placed into each canal. A radiograph was taken to confirm conefit prior to obturation (Figure 4b). The previously verified gutta-percha cone was coated with Endosequence BC Sealer (Brasseler USA), then inserted to working length to complete obturation, and a periapical radiograph was taken (Figure 4c).

The obturation was cut off at the canal orifice level with a hot instrument and was ready for restoration.

The fractured segment of the CI and remaining tooth surfaces on the lateral and central incisors were etched with 37% phosphoric acid gel, then rinsed and dried after 30 seconds. A thin layer of dentin bonding agent (OptiBond [Kerr]) was applied with a microbrush to all previously etched surfaces, then light-cured. A thin lining of flowable composite resin (Herculite Ultra Flow [Kerr]) was applied to the teeth and the fragment that had received the dentin adhesive.

The fragment was carefully repositioned on the tooth from which it had fractured with the palatal segment, then the oblique incisal segment, and light cured. Finally, direct composite veneering was performed (ceram.x SphereTEC one [Dentsply Sirona]) for fracture segment reinforcement.

Finishing and polishing were performed using the OptraPol NG finishing and polishing kit (Ivoclar Vivadent). The following steps were taken for final results: First, the shape of the tooth was checked and then approached for line angle corrections, then the incisal embrasure was contoured.

Before finalizing the shape, the vestibular contour of restoration was verified and shaped accordingly. After correcting the shape, contour, and volume of the restoration, interproximal polishing and the removal of cervical excess were performed. Final polishing was accomplished with Universal Polishing Paste (Ivoclar Vivadent) using a rotary soft brush.

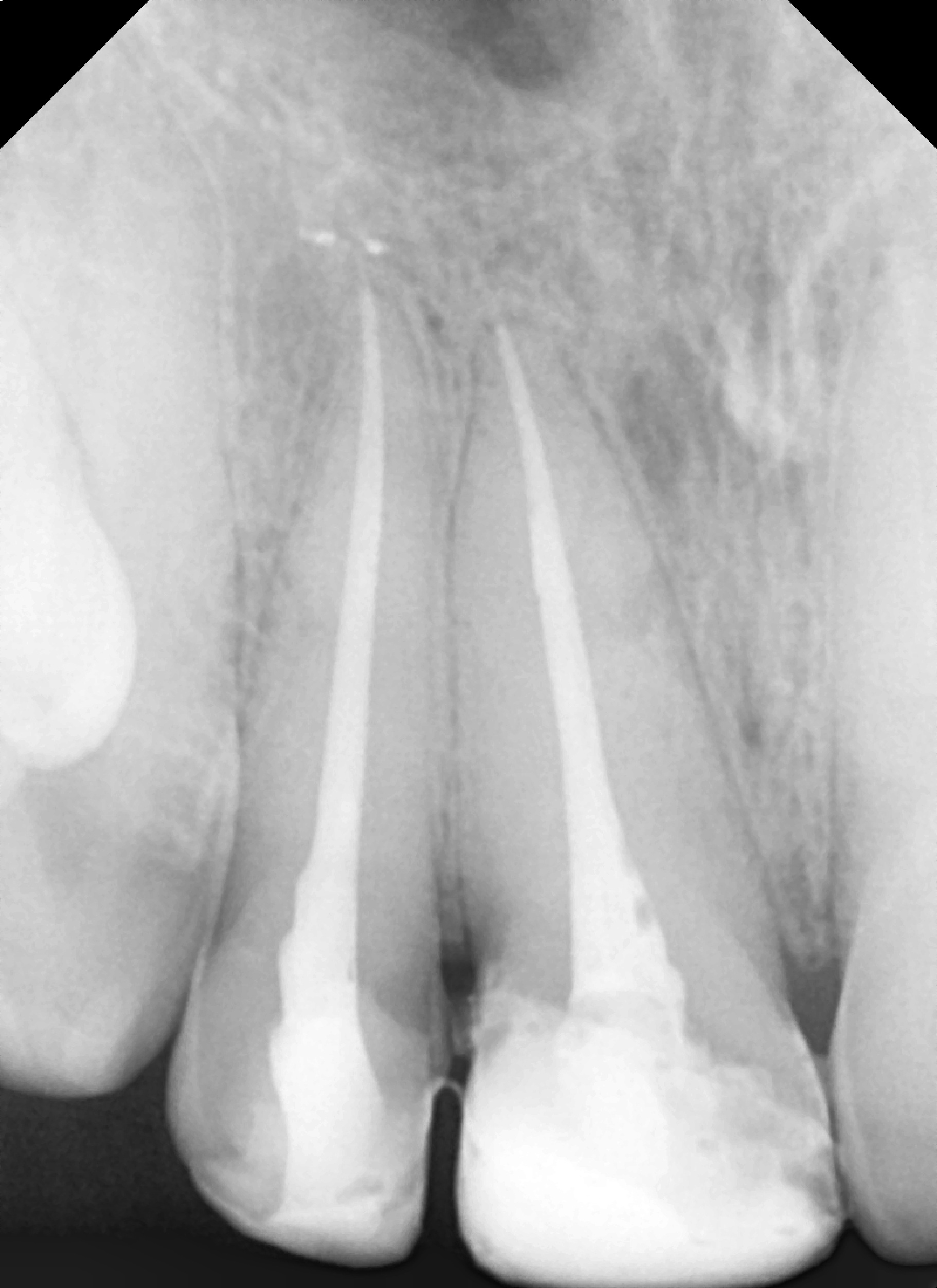

A final aesthetic result was achieved. A final radiograph was taken to document the completed treatment (Figure 4d).

Figure 4d – (Figure 4. Radiographs of the endodontic steps of treatment of the maxillary right lateral and central incisors: (a) working length, (b) try-in of master GP cone, (c) obturation, and (d) following reattachment of the fractured segment.)

Form; function; and, most importantly to the patient, aesthetics were restored (Figure 5).

A postoperative, 24-hour follow-up appointment is mandatory to verify any occlusal issues and allow adjustment, as necessary.

After a one-month recall visit, the case showed satisfactory outcomes verified by radiographic examination.

Figure 5. Clinical presentation of the completed restorative treatment with reattachment of the fractured central incisor and restoration of the lateral incisor with a bonded composite.

DISCUSSION

A nonsurgical approach, reattachment is regarded as the most conservative choice of treatment. Patients’ awareness about treatment limitations and their cooperation are important for a good prognosis. Tooth fragments themselves are highly aesthetic biological materials that eradicate the mismatch of restorative material shades, translucency, contour, and original surface texture. The process is less time-consuming because newer advancements in the reattachment of tooth fragments are possible due to the dental adhesive system.4

Various preparations for fractured segments are being employed to aid in retention, such as enamel beveling, a V-shape internal enamel groove, internal dentinal grooves, external chamfer, over-contours, simple reattachment, etc.5,6

Such studies on shear strength have shown that materials and bevels do not improve the fracture resistance of the tooth. Fracture resistance increases 40% to 60% when the sample was prepared with an enamel chamfer, and 90% fracture resistance was achieved with internal dentin grooves and overcontoured bonding.7,8

A simple reattachment technique can be performed when the fractured segments fit well together on the tooth. Overcontouring or chamfer preparation is preferred when more enamel structure is compromised (ie, fragments missing). The direction of the fracture line when it is apical-labial-lingual is an unfavorable pattern because of decreased resistance to labially applied forces. But a fracture line in an incisal-labial-lingual direction is a favorable pattern due to typical functional loading patterns.

Due to the amount of lingual support, both patterns played an important aspect in strengthening and enhancing the rate of the vitality of reattached tooth-adhesive-fragment complex with masticatory forces.4,7 If more apical-labial-lingual options or an intraosseous fracture line presents, the treatment of choice may be orthodontic extrusion, followed by placement of a post (metallic or fiber) to retain a full-coverage crown.

Another alternative is surgical treatment with a tissue flap, crown lengthening with minimum osteotomy for better accessibility, and maintaining biologic width to improve bonding.8

The most commonly employed techniques for fragment reattachment utilize a dentin-bonding agent (DBA) with flowable resin composite materials. But other materials, such as self-cured composite, have shown the highest fracture resistance, followed by light-cured resin and, lastly, DBA.9

The type of preparation utilization and design placement did not improve the fracture strength, and the incisal edge reattachment restored approximately half the fracture resistance of sound teeth.9 Fracture studies using different materials found that when composite resin was used to reattach the damaged tooth fragments, superior strength was reported compared to both a chamfer preparation at the margins and a simple reattachment technique.10

Factors affecting the longevity for reattachment depend on the fracture location, fractured remnants, periodontal status pulpal condition, root completion, biological tooth width, occlusion harmony, operative time, and affordability.5 For the fractured tooth in this case report, which was initially in poor condition, a simple reattachment technique was used.

The reattached tooth segment can be strengthened by placement of a thin layer of resin on the inner aspect of the fragments with resin reinforcement to increase resistance to occlusal loading during function.

CONCLUSION

This case report demonstrates that reattachment is the conservative procedure of choice that restores the aesthetics as well as the function of the natural tooth for the patient. There are several preparation techniques, designs, and materials used for the reattachment of fractured tooth segments in different studies and case reports. The main goal is to restore natural tooth structure with minimal intervention dentistry. The original tooth establishment needs an experienced clinician with good clinical skills to achieve this goal.

References

1. Lam R. Epidemiology and outcomes of traumatic dental injuries: a review of the literature. Aust Dent J. 2016;61 Suppl 1:4-20. doi:10.1111/adj.12395

2. Lam R, Abbott P, Lloyd C, et al. Dental trauma in an Australian rural centre. Dent Traumatol. 2008;24(6):663–70. doi:10.1111/j.1600-9657.2008.00689.x

3. Pagadala S, Tadikonda DC. An overview of classification of dental trauma. IAIM. 2015;2(9):157–64.

4. Choudhary A, Garg R, Bhalla A, et al. Tooth fragment reattachment: An esthetic, biological restoration. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2015;6(1):205–7. doi:10.4103/0976-9668.149123

5. Garcia FCP, Poubel DLN, Almeida JCF, et al. Tooth fragment reattachment techniques—a systematic review. Dent Traumatol. 2018;34(3):135–43. doi:10.1111/edt.12392

6. Thapak G, Arya A, Arora A. Fractured tooth reattachment: a series of two case reports. Endodontology. 2019;31:117–20. doi:10.4103/endo.endo_140_18

7. Badami V, Reddy SK. Treatment of complicated crown-root fracture in a single visit by means of rebonding. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(6):646–50. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0246

8. VamsiKrishna R, Madhusudhana K, Swaroopkumarreddy A, et al. Shear bond strength evaluation of adhesive and tooth preparation combinations used in reattachment of fractured teeth: an ex-vivo study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2015;33(1):40–3. doi:10.4103/0970-4388.148975

9. Taguchi CM, Bernardon JK, Zimmermann G, et al. Tooth fragment reattachment: a case report. Oper Dent. 2015;40(3):227–34. doi:10.2341/14-034-T

10. Soliman S, Lang LM, Hahn B, et al. Long-term outcome of adhesive fragment reattachment in crown-root fractured teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2020;36(4):417–26. doi:10.1111/edt.12550

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Pathak is a private practitioner, consultant endodontist, and senior lecturer in Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India.

Dr. Sharma is in the Reader Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics at the Institute of Dental Education & Advance Studies (IDEAS) in Gwalior.

Dr. Kurtzman is in private practice in Silver Spring, Md.

Dr. Lau is a professor at the Manipal College of Dental Sciences at the Manipal Academy of Higher Education and a professor at IDEAS in Gwalior.

Disclosure: The authors report no disclosures.