A large number of pathological conditions may affect the jaws. These can vary from common to very rare disease entities. These diseases can be similar to those affecting other bones of the skeleton, though many lesions of the jaws are unique due to their anatomic differences. Most notably this unique feature involves odontogenic structures (eg, teeth and periodontium). Nevertheless, these pathoses need to be recognized and properly diagnosed following diagnostic procedures generally utilized (eg history and physical examination).1,2 Helpful in this regard is a simplistic and useful classification system. The MIND classification system has been proposed based on an etiopathogenic approach.1,2 The purpose of this article is to discuss this system for evaluating pathologic changes in bone and of course the radiograph is an essential aspect of the diagnostic approach. Radiographic classification systems3 (eg, radiolucent, radiopaque, etc) are also available and useful to complement this particular etiopathogenic approach.4

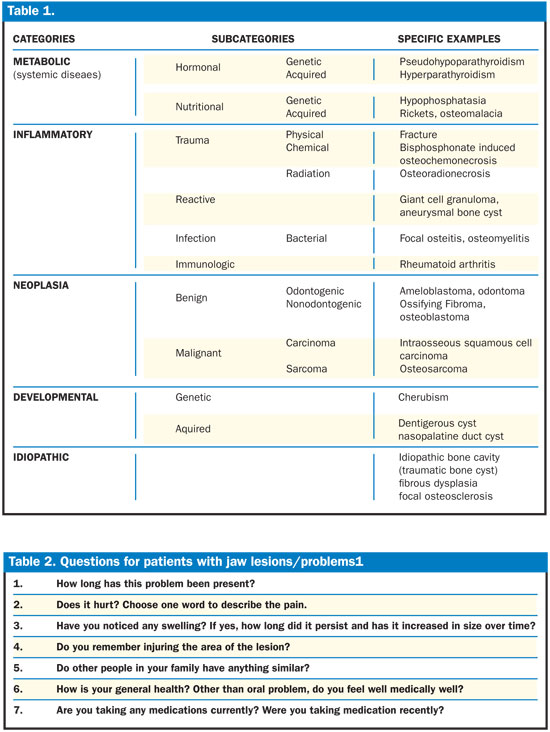

The term MIND stands for the 4 major divisions of the classification system: Metabolic (systemic diseases)(eg, hypophosphatasia, hyperparathyroidism, etc), Inflammatory (eg, periodontal inflammation, osteomyelitis, etc), Neoplasia (eg, osteoblastoma, ossifying fibroma, etc) and Developmental (eg, stafne defect, cherubism, etc). All the categories have been further divided into subcategories (Table 1). An idiopathic category has also been added to include the lesions with unknown etiologies.

|

|---|

METABOLIC

The metabolic category can be subcategorized into nutritional and hormonal and further divided into those diseases that are of genetic or acquired origin. The acquired defects associated with osseous metabolism can be seen in the general skeleton as well as the jaws and these would include vitamin C, D and Ca/P metabolism, associated with deficiencies in intake. Other pathologic conditions affecting metabolism may be of genetic type (eg vitamin D resistant rickets, hypophosphatasia and osteogenesis imperfecta).

INFLAMMATORY

Inflammation is the complex biological response of tissues to harmful stimuli such as trauma and irritants. It is a protective attempt by the body to remove the injurious stimuli, as well as initiate the healing proces. The classic signs of inflammation are redness, pain, swelling, heat and loss of function.

Inflammatory lesions are divided into four subcategories: Lesions caused by extrinsic factors (physical agents), reactive lesions, infections and the lesions of immunologic origin. External factors like radiation and chemical agents can lead to inflammatory lesions such as osteoradionecrosis and osteochemonecrosis (localized death of the osseous tissue). The reactive subcategory includes lesions occurring in response to chronic irritation. The intraosseous reactive lesions like central giant cell granuloma and the aneurysmal bone cyst are occasionally seen in the jaws. The third subcategory includes the intraosseous lesions caused by the infections in the oral cavity. Bacterial infections in the oral cavity are mostly seen in the alveolar bone, leading to periodontitis and pulpal necrosis, which can lead to periapical inflammatory lesions. Rarefying osteitis or a periapical radiolucency is the collective term used for any periapical lesion of inflammatory origin, which includes a cyst, granuloma or an abscess.5The last subcategory in the inflammatory division is the immunologic type. This includes lesions such as rheumatoid arthritis, which may be presented as a chronic disorder of the temporomandibular joint disorder.

NEOPLASIA

The term neoplasia refers to a uncontrolled growth of tissue, that results from an abnormal proliferation of cells. The neoplastic lesions are broadly divided into two major categories on the basis of their ability to metastasize—benign and malignant.

Benign neoplasms are dysmorphic proliferations of tissues that are characterized by the lack of metastasis. These have been further subcategorized as odontogenic and nonodontogenic on the basis of the tissue of origin. The odontogenic neoplasms include the lesions derived from parts of the odontogenic apparatus (eg, ameloblastoma, ameloblastic fibroma, adenomatoid odontogenic tumor, and odontoma). The nonodontogenic neoplasms include the lesions of the osseous tissue that are unrelated to the tooth development but originate from osseous tissue (eg, osteoblastoma, desmoplastic fibroma of the bone, and ossifying fibroma).

Malignant neoplasms can be subcategorized on the basis of tissue of origin into sarcomas and carcinomas. Sarcomas include the malignancies of mesenchymal origin (eg, Ewing’s sarcoma, osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma and multiple myeloma). Carcinomas include the malignancies of epithelial origin.The odontogenic carcinomas result from the malignant alteration of the residuals of the odontogenic apparatus [eg, reduced enamel epithelium and dental lamina rests (Serres)].

DEVELOPMENTAL

The developmental category includes pathologic changes in bone that develop both as a genetic or acquired defect. However, in many of these lesions the exact etiologic factors have not been yet determined. The genetic determinants of some of these developmental conditions have been identified and this list is growing steadily. Many of the acquired conditions have been linked to both osteogenesis and facial development (eg, nasopalatine cyst) and also to odontogenesis (eg, follicular cysts, dentigerous cysts). Other developmental conditions include lesions such as the Stafne defect or an arteriovenous malformation.

IDIOPATHIC

Unfortunately there are large numbers of jaw lesions for which the etiology is unknown at this time (eg, fibrous dysplasia, idiopathic bone cavity or traumatic bone cyst, focal osteosclerosis, etc). They cannot be clearly categorized in any one category presently. An idiopathic category has thus been added to include all such lesions with unknown etiology.

HISTORY TAKING

An important part of the diagnostic process is the history taking of a lesion, including both the dental and medical history. A few examples of the major questions that need to be asked in order to reach a definitive diagnosis have been listed below (Table 2). The answers to these questions will be able to provide the clinician with a better understanding of the lesion and help in deciding on the etiopathogenesis.

The first question to be posed to the patient is “How long has this problem been present?” A short history of the disease will hint at inflammatory or malignant causes, whereas, a history of the lesion being present since birth or of long duration would increase the possibility of a developmental disorder.

The next question is “Does it hurt? Choose one word to describe the pain.” Since pain is one of the first symptoms to be noted by the patient, it can be expressed by the patient more elaborately. The presence of pain, its intensity and duration helps differentiate between the possible diagnoses. The presence of pain will attest for inflammation, as pain is one of its five classic symptoms. The description of pain in terms of its intensity and duration helps narrow the list of the causative factors and can be helpful, especially with odontogenic infection (pulpal). Other more ominous symptoms (e.g. paresthesis) may indicate a neoplastic condition.

“Have you noticed any swelling? If yes, how long did it persist and has it increased in size over time?” A swelling in the jaws could be an indication of a neoplastic growth in the bones (eg, ameloblastoma, ossifying fibroma, etc) or may be a deformity of the bone due to trauma or a developmental disorder (eg, cherubism, dentigerous cyst, etc). An inflammatory lesion caused by bacterial infection may also present as a swelling, usually of a short duration.

An important question to ask would be “Do you remember injuring the area of the lesion?” Fracture is a common result of trauma to jaw bones. This can also lead to a nonvital tooth and subsequent periapical pathosis of pulpal origin. These periapical lesions usually heal completely, if the source of irritation is removed (eg, endodontics).

“Do other people in your family have anything similar?” A condition that tends to occur more often in family members increases the probability of it being genetically inherited. This type of lesion may be placed in the genetic division of the developmental category (eg, Cherubism).

The clinician must ask the patient “How is your general health? Other than the oral problem, do you feel medically well?” If the patient presents with good general health, that would lessen the possibility of a metabolic or systemic disease. The presence of other systemic signs or symptoms such as fever, pain in different parts of the body, bone fractures, etc. may indicate undetected systemic diseases.

“Are you taking any medications currently? Were you taking medication recently?” The answer to this question verifies the previous question. If the patient has been taking medication for a long time, the definition of good health would be different for the patient. The stability of the condition for that person would be equivalent to good general health. But the lesion could be a secondary reaction to the primary disease induced by the medication (bisphosphonate associated osteonecrosis).

CONCLUSION

The MIND acronym is hopefully a useful tool that clinicians may utilize in helping to form a differential diagnosis, along with a careful history and physical examination. Various imaging modalities are extremely useful as well as the histopathologic evaluation of the jaw lesions, to allow a correct and definitive diagnosis. Of course, this will allow for a plan that ensures correct treatment.

References

- Carpenter WM, Jacobsen PL, Eversole LR. Two approaches to the diagnosis of lesions of the oral mucosa. CDA Journal. 1992;27:619-624.

- Jacobsen PL, Carpenter WM. MIND: A method of diagnosing oral pathology. Dentistry Today. 2000;19: 58-61.

- Bhaskar SN. Roentgenographic interpretation for the dentist. St Louis, Mo: Mosby Inc; 1970.

- White SC, Pharoah MJ. Oral radiology-principles and interpretation 6th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby/Elsevier; 2009.

- Sapp JP, Eversole LR, Wysocki GP. Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology 2nd edition. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby-Year Book Inc; 2004.

Dr. Carpenter earned a DDS from the University of Pittsburgh and a MS in oral biology from George Washington University. He retired as a colonel after a 21-year career with the US Army Dental Corps where he was Chief of the Divisions of Pathology and Professional Development at the US Army Institute of Dental Research at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center. Dr. Carpenter currently is Professor and Chairman, department of Pathology/Medicine, University of the Pacific, Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry, San Francisco, Calif. He is a member of many professional societies, including the American Academy of Oral Medicine (past president) and the American Academy of Oral Pathology, both of which he holds Fellowship and Diplomatic Status. He can be reached at wcarpent@pacific.edu.

Dr. Sidhu is a Diplomate American Board of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology and is the director of Radiology and a clinical assistant professor in the department of Dental Practice at University of the Pacific, San Francisco, Calif. She conducts private practice in maxillofacial radiology at Pacific Dental Diagnostics. Dr. Sidhu received her DDS degree from the University of the Pacific Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry. She also holds a Masters in Science degree in Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology from the University of Iowa College Of Dentistry. She has published articles and lectured to various dental organizations. She can be reached at g_sidhu@pacific.edu.

Dr. Kaur received her BDS from Dashmesh Institute of Research and Dental Sciences, India. She is currently a research assistant and an adjunct faculty with the Department of Dental Practice at the Radiology clinic at University of the Pacific Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry, San Francisco, Calif. She is also a member of the Indian Dental Association. She can be reached at skmann@gmail.com.