INTRODUCTION

In the field of aesthetic dentistry, new materials are constantly being introduced, yet the techniques themselves have not seen any changes in the last 3 decades—that is, until now.

The optical properties of enamel are influenced by its chemical composition. Visualization using exclusive daylight does not always suffice to allow an in-depth analysis and evaluation of the tooth structure, thereby risking jeopardizing or even compromising shade choice for an optimal shade match under different lighting conditions.1 Fluorescent light was successfully applied to overcome the dilemma. Excitation using fluorescent light has been shown to ease resin identification and differentiation from natural tooth structure.2-5

The surgical part, as well as the restorative part of the depicted treatment sequence, was aided by the use of fluorescence-enhanced theragnosis—in this case, the REVEAL (Designs for Vision) technology: “A defined light spectrum emitted by an external source directed intraorally has the potential to create photoluminescence (emission) due to autogenous properties (fluorescence) of the natural tooth structure as well as due to bacterial side products defined as porphyrins. To allow visualization of the emission wavelength (fluorescence), filters are needed.”1

Aesthetics Simplified With Fluorescence

Regularly used loupes can offer magnification but don’t allow the user to see materials in different hues as fluorescence loupes do. This technology makes it easy to see the different hard tissues and materials and eliminates the professional “guesswork” associated with ideal veneer preparations. The clinician can also see the hard-to-discern interface between restorative materials and tooth structure, such as the remaining bonding materials on the tooth surface and excess resin/cement remnants at the restoration margins.

During the following case presentation, we will take a step-by-step, descriptive approach to show how this technology has aided in the completion of this aesthetic case.

CASE REPORT

A 15-year-old patient presented after completion of orthodontic treatment with chief complaints of a “gummy smile” and, as per patient description, “dinosaur teeth” (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Preoperative smile showing excessive gingival display and lateral incisors of different, inadequate sizes.

A comprehensive evaluation showed that the patient had peg laterals of different sizes and beautiful remaining dentition with adequate mesiodistal dimensions. Due to excessive gingival display, the crown lengths from her maxillary central incisors all the way posteriorly to the first molars were not fully visible and therefore gave the impression of inadequately sized teeth.

The decision was made to refer the patient out for crown lengthening surgery prior to the commencement of the restorative treatment phase.

Excessive gingival display caused by altered passive eruption is a clinical condition where the alveolar crest of bone supporting anterior teeth approximates the CEJ, resulting in gingiva covering more of the clinical crown than what is considered to be within aesthetic limits.6 Aesthetic crown lengthening is a predictable and effective way to increase the amount of clinical crown showing in patients with excessive gingival display.7 Aesthetic crown lengthening via gingivectomy, in combination with osseous resection surgery, has become the most widely used and accepted method to accomplish this procedure. It has repeatedly been reported that gingivectomy alone is highly prone to relapse.8,9 Other factors, such as bacterial plaque, can also lead to the development of gingivitis.10 Inflammation of the gingival tissues can cause an inflated appearance of the interproximal papilla that distorts the gingival margin.11 Elimination of bacterial plaque allows for ideal scalloping and contouring of the gingival margins, a crucial component to obtaining ideal results with respect to symmetry and aesthetics surrounding the anterior teeth. Bioluminescence is a predictable and effective way to ensure complete removal of the bacterial plaque prior to surgery and during postoperative visits to idealize the results of the surgery through the healing phase.

Surgical Treatment

Local anesthesia was administered, and a gingivectomy was completed on teeth Nos. 4 to 13 to idealize clinical crown display (Figure 2).

A full-thickness mucoperiosteal flap was reflected on the facial surfaces of teeth Nos. 3 to 14 past the mucogingival junction. No flap was reflected on the palatal aspect. An ostectomy and osteoplasty with rotary instruments were completed to establish a bone margin 3 to 4 mm from the CEJs of teeth Nos. 4 to 13 (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Gingivectomy performed on tooth No. 8 for visualization of desired tissue height, pre-bone removal.

Figure 3. Full-thickness mucoperiosteal flap reflected from teeth Nos. 3 to 14 and bone removal 3 to 4 mm away from the CEJ.

The establishment of the facial bone margin 3 to 4 mm away from the CEJs of anterior teeth has been shown to create the most stable gingival margin post-op.7 A gingival margin positioned less than 3 mm from the bone margin on facial surfaces of anterior teeth tends to experience gingival rebound of approximately 1 mm.7 It is also necessary to ensure that adequate bone removal is completed past the line angles toward the interproximal height of bone without removing the peaks of bone directly interproximally. Post-op, interproximal papillae will appear bulbous if insufficient bone is removed near the line angles. Avoidance of a palatal flap and removal of interproximal peaks of bone assist in maintaining complete interproximal papilla fill after healing. Hand instrumentation was used to clean the root surfaces to aid in the reattachment of the flap margin and establishment of a new, apically positioned gingival margin. Interrupted 4-0 chromic gut sutures were used to fixate the flap (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Gut sutures in place after bone and soft-tissue removal.

The patient was instructed to use a chlorhexidine mouth rinse twice daily with gentle swishing for 10 days post-op. It was recommended to take 400 to 600 mg of ibuprofen orally every 6 hours for the first 48 hours following the procedure to reduce swelling, inflammation, and post-op discomfort. The patient presented for a 2-week post-op visit to ensure healing was uneventful. This patient did not experience any post-op complications. In approximately 10% of patients, gingival margins after crown lengthening procedures may continue to change up to 6 months after crown lengthening surgery is completed.12 However, in the vast majority of patients, gingival margins are stable at 3 months after a crown lengthening procedure.13 This should be considered when using aesthetic crown lengthening in conjunction with restorative dentistry to ensure optimal aesthetics are accomplished for patients.

Following the post-crown lengthening surgery healing phase, the patient was reappointed, and impressions were taken for the fabrication of bleaching trays. The patient bleached for approximately 2 weeks with LumiSmile 16% (DenMat). As a result, she attained significant lightening of her entire dentition (Figure 5).

Using a duplicate of her models, I personally waxed up teeth Nos. 7 and 10 to my desired, proposed shape (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Post-healing view of maxillary anterior dentition.

Figure 6. Wax-up of lateral central incisors.

This was an important step to complete because it gave me 5 different benefits:

1. It allowed me to see what shape facially and incisally best fit aesthetically with the patient’s dentition, keeping the harmony of her entire smile in mind.

2. It gave the porcelain technician a good idea of what I was looking for in terms of general shape.

3. It allowed me to measure and assess the gingival tissue heights on the teeth to be prepared.

4. It allowed me to have a stent made prior to the prep appointment for easy temporary fabrication.

5. It allowed the patient and myself to evaluate the custom-made temporaries and be able to make desired changes prior to the fabrication of the final veneers.

The preparation appointment was started by anesthetizing the patient with one carpule of lidocaine with 1:100,000 Epinephrine, followed by gingival recontouring on teeth Nos. 7 and 10. Although the general shape was adequate, there were some small differences between the gingival contours of those teeth that I felt needed to be addressed in the hope of attaining an ideal outcome. This was accomplished with the help of an electrosurgery unit (Figure 7).

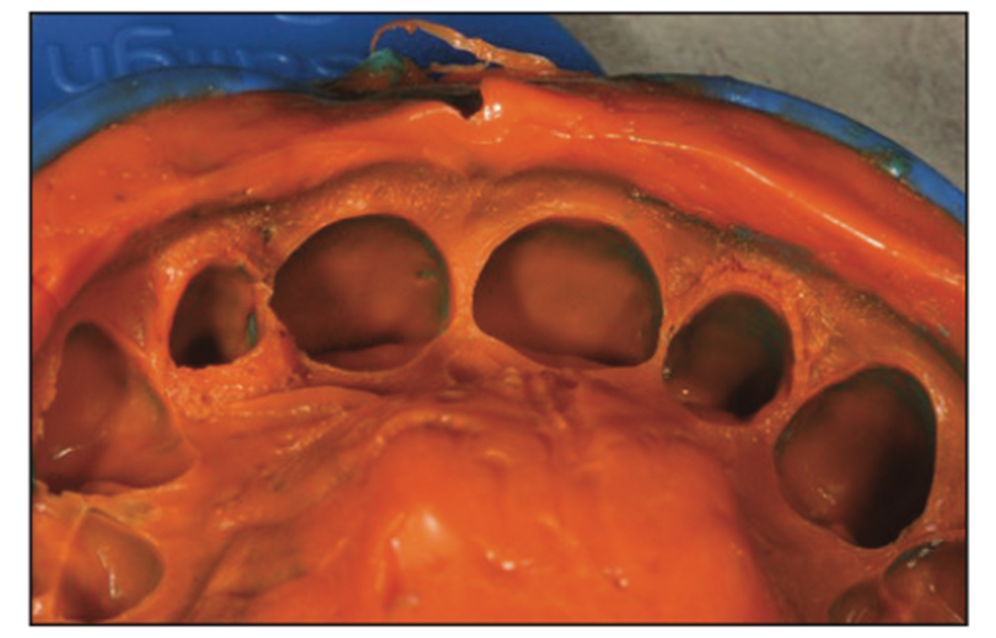

The REVEAL glasses were then implemented to clearly navigate the enamel on the deformed lateral incisors and execute a preparation that was kept entirely in enamel. With the help of the fluorescence technology, I was able to clearly see the areas that had thinner enamel development and avoid excessive removal. Upon completion of the preparations, a full-arch impression was taken with a polyvinyl siloxane material (Kerr) in the sandwich technique style, which captured the marginal detail extremely well (Figure 8).

Figure 7. Minor gingivectomy performed at prep appointment for teeth Nos. 7 and 20 to gain ideal tissue contours.

Figure 8. Polyvinyl siloxane impression taken of prepped teeth Nos. 7 and 10.

The preparations were then spot-etched and temporized. OptiBond (Kerr) was spot-cured onto the preparation. The temporary veneers were then fabricated directly with Protemp temporary material (3M) and partially bonded into place. Upon final evaluation of the temporary veneers, small adjustments were made to their shapes, and the results were photographically recorded for better lab communication (Figure 9).

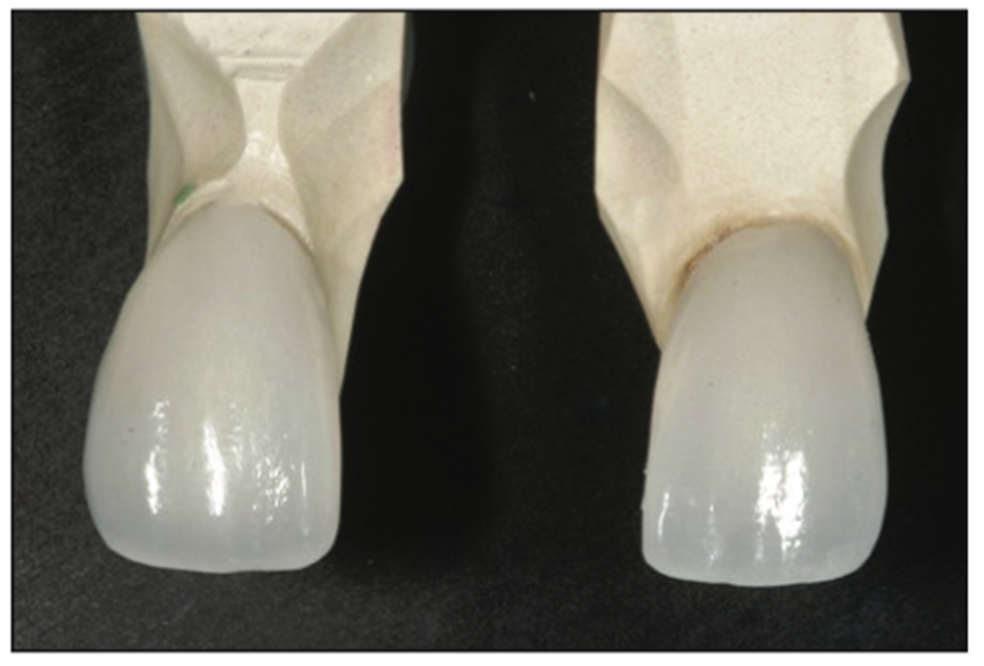

The feldspathic veneers were then artistically created by Edwin Fajardo with Excel Dental Studios, Chatsworth, Calif (Figure 10).

Figure 9. Custom temporaries in place.

Figure 10. Newly fabricated feldspathic porcelain veneers on stone dyes.

At the seating appointment, the patient was anesthetized, and the REVEAL loupes were again implemented (Figure 11). This time, they allowed me to see the temporary material and remove it with ease. Additionally, they allowed me to clearly see the area I had spot-etched and spot-bonded for the adhesion of the temporaries and clean the enamel of undesired remnants. This is extremely important because often with regular loupes, one cannot see small band/composite remnants on the facial surface, and practitioners sometimes end up with either cracked veneers or rocking restorations. The veneers were then tried in for fit and bonded into place with NX3 Nexus Third Generation Universal Adhesive Resin Cement (Kerr). For all bonding procedures, the curing light used was the Radii Xpert (SDI).

Figure 11. REVEAL loupes (Designs for Vision).

After complete curing, removing all visible excess luting agent, and polishing of the margins and occlusal adjustments, the REVEAL loupes were again activated with the fluorescent light, and thorough marginal integrity was checked. Small pieces of any remaining excess, hardened luting material were also removed. Not removing these miniscule amounts of retained luting resin from the margins would likely have had future periodontal implications.

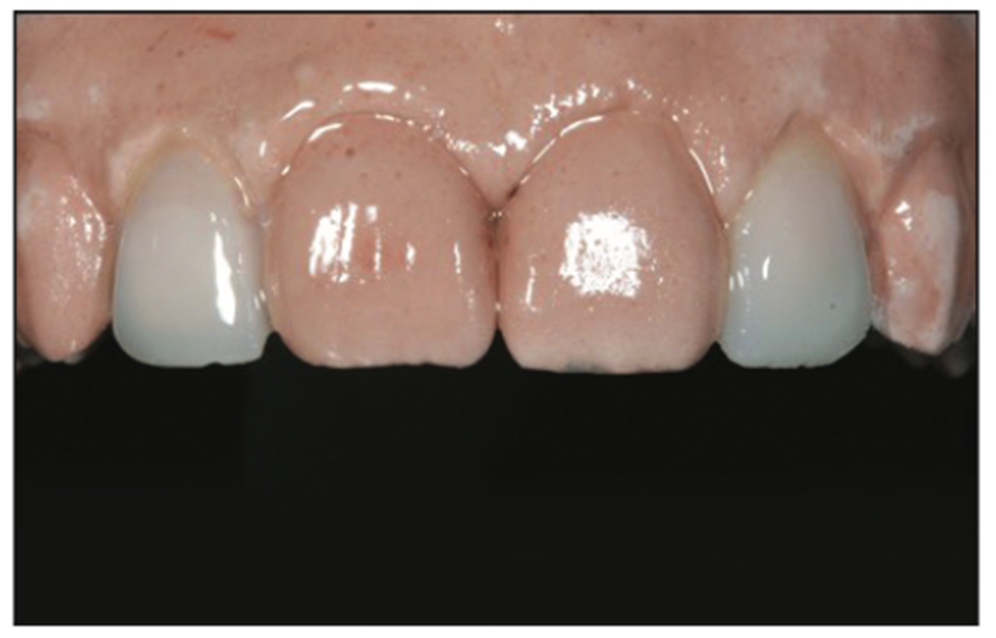

The patient was then photographed for final documentation (Figures 12 to 14).

Figure 12. Veneers seated and bonded in place.

Figure 13. The postoperative smile.

Figure 14. (a) The pre-op smile compared to (b) the post-op smile, 2 weeks post treatment completion.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the use of fluorescence improved the quality of treatment we were able to deliver by allowing us to see details and make corrections accordingly. In our professional opinion, this system will become the newest indispensable arsenal addition to every modern dental practice.

REFERENCES

1. Lee JY, Kim HJ, Lee ES, et al. Quantitative light-induced fluorescence as a potential tool for detection of enamel chemical composition. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2020;32:102054. Doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.102054

2. Dettwiler C, Meller C, Eggmann F, et al. Evaluation of a Fluorescence-aided Identification Technique (FIT) for removal of composite bonded trauma splints. Dent Traumatol. 2018;34(5):353–9. Doi:10.1111/edt.12425

3. Stadler O, Dettwiler C, Meller C, et al. Evaluation of a Fluorescence-aided Identification Technique (FIT) to assist clean-up after orthodontic bracket debonding. Angle Orthod. 2019;89(6):876–82. Doi:10.2319/100318714.1

4. Conceição LD, Masotti AS, Forgie AH, et al. New fluorescence and reflectance analyses to aid dental material detection in human identification. Forensic Sci Int. 2019;305:110032. Doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.110032

5. Pretty IA, Smith PW, Edgar WM, et al. The use of quantitative light-induced fluorescence (QLF) to identify composite restorations in forensic examinations. J Forensic Sci. 2002 Jul;47(4):831–6.

6. Miron H, Calderon S, Allon D. Upper lip changes and gingival exposure on smiling: Vertical dimension analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;141(1):87-93. Doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.07.017

7. Deas DE, Mackey SA, Sagun RS Jr, et al. Crown lengthening in the maxillary anterior region: a 6-month prospective clinical study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2014;34(3):365–73. Doi:10.11607/prd.1926.

8. Allen EP. Use of mucogingival surgical procedures to enhance esthetics. Dent Clin North Am. 1988;32:307–30.

9. Camargo PM, Melnick PR, Camargo LM. Clinical crown lengthening in the esthetic zone. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:487–98.

10. Loe H, Theilade E, Jensen SB. Experimental gingivitis in man. J Periodontol. 1965;36:177–87. Doi:10.1902/jop.1965.36.3.177

11. Engelberger T, Hefti A, Kallenberger A, et al. Correlations among Papilla Bleeding Index, other clinical indices and histologically determined inflammation of gingival papilla. J Clin Periodontol. 1983;10(6):579–89. Doi:10.1111/j.1600-051x.1983.tb01296.x

12. Brägger U, Lauchenauer D, Lang NP. Surgical lengthening of the clinical crown. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19(1):58-63. Doi:10.1111/j.1600-051x.1992.tb01150.x

13. Lanning SK, Waldrop TC, Gunsolley JC, et al. Surgical crown lengthening: evaluation of the biological width. J Periodontol. 2003;74(4):468–74. Doi:10.1902/ jop.2003.74.4.468

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Cuevas received her DDS degree from the University of Texas, San Antonio, where, post graduation, she also served on the faculty in the aesthetic restorative department for several years. She is a member of numerous dental associations and has served as a contributing editor for the Journal of Cosmetic Dentistry. Dr. Cuevas has published numerous professional articles on direct and indirect bonding techniques and has lectured nationally and internationally on aesthetic dentistry. She is an active consultant for several dental manufacturers in the area of new product development and refinement. Dr. Cuevas is an evaluator for and serves on the board of REALITY Ratings & Reviews. Dr. Cuevas maintains a private practice, the Institute of Esthetic Dentistry, in San Antonio, emphasizing aesthetic and restorative dentistry, and is a clinical faculty assistant professor at the University of Texas School of Dentistry in San Antonio. She can be reached at simona.dds@gmail.com.

Dr. Walker grew up in Boulder, Colo, and attended the University of Colorado School of Dental Medicine. He moved to Texas to complete his specialty training in periodontics and received his Master’s degree in Dental Science from the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Dr. Walker conducted clinical research relating to bone grafting and dental implants during his residency for completion of his Master’s degree that was published in the Journal of Periodontology. He can be reached at info@alamoimplantcenter.com.

Disclosure: The authors report no disclosures.