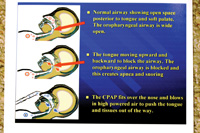

Within the past 10 years, there has been a huge increase in the diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), by the medical community. Because there are many patients who are unable to tolerate continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy (Figure 1) prescribed by medical doctors, dentistry has a tremendous new opportunity to help patients in the treatment of sleep disorders. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) has designated dental sleep appliances as the top nonsurgical alternative for the CPAP intolerant patient. In addition, in February of 2006, the AASM designated dental sleep appliances to be a viable treatment for mild to moderate sleep apnea.1 This has opened the door for dentists who are trained to treat snoring/mild-moderate sleep apnea, and who want to help CPAP intolerant patients.

Dentists now have more advanced appliance choices for sleep breathing disorders. The purpose of this article is to introduce an example of a new concept in sleep therapy using a single-arched mandibular (or maxillary) oral appliance. In addition, it is important to note that we have better techniques for diagnostics and the fitting of these appliances, including the use of 3-dimensional (3-D) dental imaging. Using such techniques, dentists are capable of achieving high success rates consistently with their snoring and CPAP-intolerant patients.

SNORING

Snoring is caused by a restriction in the size of the airway with rapidly moving air vibrating the tissues in the oropharyngeal airway. If the tongue is restrained from closing the airway, the snoring dissipates.

Fifty-two percent of all Americans age 40 years or older snore.2 Twenty-seven percent of all couples more than 40 years old sleep apart because of snoring problems. A recent article in the Wall Street Journal stated that new housing construction was beginning to include 2 master bedrooms in new homes.3 In fact, the problem of bothersome snoring within households has become so widespread that separate sleeping quarters are frequently desired.

Without a reliable and broad-based remedy in use, snoring has become a ubiquitous American cultural phenomenon.

CONTINUOUS POSITIVE AIRWAY PRESSURE: HIGHLY SUCCESSFUL, HIGHLY REJECTED

|

|

|

Figure 1. Patient sleeping using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy. |

Figure 2. Diagrams show how CPAP functions. |

After weight loss, the number-one medical treatment for snoring and OSA is CPAP therapy. It is an extremely successful treatment modality for these problems. (Figure 2 shows how the CPAP device functions.)

However, CPAP therapy presents its own difficulties since it is not tolerated by 50% to 60% of the patients who are treated with it.4,5 Some of these difficulties include dry/stuffy nose, irritated facial skin, sore eyes, and headaches. If the CPAP device is not properly adjusted, the patient may get stomach bloating and discomfort while wearing the mask. Without the ability to wear the CPAP device, these patients are left to “fall through the cracks” untreated. Where do they go, and what hope do they have for the successful treatment of their condition?

ORAL SLEEP APPLIANCES

|

|

| Figure 3. The Tap appliance, an example of a double-arch appliance that opens the bite and positions the mandible/tongue forward. |

Figure 4. The SUAD appliance, another example of a double-arch appliance. |

|

|

Figure 5. Tongue-retaining appliance that holds the tongue forward with suction. |

The answer for people who are CPAP intolerant lies with dental sleep appliances. In the proper diagnosis and use of oral sleep appliances, dentistry has a workable solution for sleep apnea and snoring. With this, dentistry has been handed a major responsibility in the treatment of snoring and OSA.

For the most part, the dental devices currently available for the treatment of snoring and OSA are double-arched appliances. Success is achieved by opening the vertical dimension and advancing the mandible forward.6 The advancement can be from edge-to-edge to, as much as, a full protrusive position. With some patients, the vertical is opened as much as 10 to 15 mm. In this way, the tongue is pulled forward and the airway opened.

Two popular double-arched sleep appliances that advance the mandible and open vertical are illustrated in Figure 3, the Tap appliance, and Figure 4, the SUAD appliance.

Another option is the tongue-retaining device (Figure 5). It holds the tongue forward by suction, created when the tongue is inserted into a rubber bubble in the front of the appliance.

Appliances like these can be successful, however, a large percentage of them can be uncomfortable since mandibular advancement can lead to jaw pain, changes in occlusion, and tempromandibular disease problems. Furthermore, what can be done once the dentist has opened the vertical, and moved the jaw forward as far as possible, without accomplishing the reduction of snoring and apneic events? The treatment is finished, unsuccessfully.

SINGLE-ARCHED APPLIANCES

In September, 2006, a new maxillary single-arch oral sleep appliance was introduced to dentistry called the Full Breath Solution (FBS). It allows the clinician to take a very different approach to treatment. Rather than pulling the tongue forward by advancing the mandible, it works by utilizing a “tail” that restrains the tongue from moving upward and backward. The tail is expanded posteriorly and inferiorly, depressing the tongue in the same manner in which the medical doctor utilizes a wooden tongue blade in an exam. The tongue is gently depressed in order to open and view the airway. In the same way, dentists can utilize the tail on the single-arch FBS oral appliance to open the airway.

In June, 2009, the mandibular single-arch FBS oral appliance was granted FDA certification, and subsequently introduced into patient care. This was the fifth FDA certification granted to the FBS appliance since 2004.

The CPAP is almost 100% successful, when tolerated, because the positive pressure of the continuous air stream pushes the tongue forward keeping the airway open. Similarly, the FBS oral appliance is successful because it depresses and restrains the tongue, inhibiting the tongue from moving up/backward and blocking the airway. An oral device that controls the tongue is able to control and open a patient’s airway, allowing more oxygen to enter the lungs, dramatically improving nighttime breathing.

|

|

|

Figures 6a and 6b. Single-arch maxillary Full Breath Solution (FBS) appliance. |

|

|

|

Figure 7. The tail of the lower FBS which can be seen here depresses the tongue and prevents it from moving posteriorly. |

Figure 8. An underside view of a mandibular FBS appliance. Two to 4 clasps are placed for retention. |

Figures 6a and 6b show the maxillary FBS oral appliance, and Figures 7 and 8 show the mandibular FBS oral appliance. The mandibular FBS single-arched appliance utilizes a posterior tongue restrainer (PTR), or “tail” to depress the tongue.

The FBS appliance gains its clinical success by small additions of acrylic to get posterior and inferior extension of the PTR (tail). This allows for more leverage in restraining the tongue. The formation of the tail, which acts exactly like a tongue depressor, prevents the tongue from its upward and backward movement resulting in an open airway and reduced/eliminated snoring.

|

|

|

Figure 9. Blue wax has been added to the tail of the maxillary FBS appliance. |

Figure 10. Blue wax has been added to the tail of the mandibular FBS appliance. |

|

|

|

Figures 11 and 12. Wax has been removed and replaced with cold-cured acrylic to the same approximate shape both a maxillary and a mandibular FBS. The tails can now function like a tongue depressor to open the airway. |

With either the maxillary (Figure 9) or mandibular appliance (Figure 10), wax is incrementally added to the tail, a little at a time, to clinically test for patient comfort and tolerance. If comfortable, the wax is removed and acrylic is added in the same approximate size and shape as the wax-up (Figures 11 and 12). In this way, the tail is expanded (from its original lab-fabricated starting point) to adequately depress the tongue.

Depression can be slight, or much deeper, depending on the patient. The question that invariably comes up is the comfort of the tail. Approximately 5% of patients complain of discomfort or irritation. In those cases, the tail is cut off. Then, approximately 3 weeks later, the tail is added back on in small increments of acrylic extensions. This approach produces a uniform success rate with patients (breathing and comfort) in the 99th percentile. When desired, acrylic can also be removed from the superior surface of tail to keep it thinner and more comfortable.

Despite the tail, the properly fabricated and adjusted FBS appliance will not cause gagging. The reason lies with the physics and effects of snoring. When a person is snoring, the tongue falls back and closes the airway from 80% to 90%. As the air flows through the constricted airway, it picks up speed as it moves through the reduced opening. This constantly speeding air desensitizes the nerve endings on the posterior section of the tongue. As a result, there is a reduction or elimination of the normal gagging reflex due to a reduction of tactile nerve endings on the tongue.

3-D IMAGING

|

|

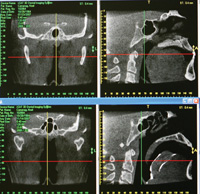

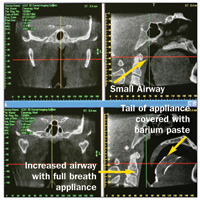

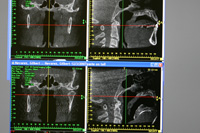

| Figure 13. In these CAT scan views, the lateral cervical view (upper right) shows the small airway caused by the posterior position of a large tongue. The lower right image is the same individual with the FBS appliance in place. |

Figure 14. These images show the increase in the size of the airway achieved with the FBS appliance. Compare the pretreatment image (upper right) with the post-treatment (lower right) image. Again, note the tongue depressing effect of the tail to depress the tongue and open the airway. |

|

|

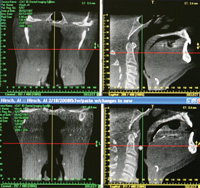

Figure 15. In the upper right, the superior posterior tip of the tail is touching the soft palate and can be a cause of discomfort. Also, the tail needs to be repositioned downward to better control the tongue. The lower right image shows the changes made to the appliance and the increased airway. |

The tail, which is the key to successfully treating the patient, is incrementally elongated and thickened in depth until the snoring is eradicated. The elongation of the tail with acrylic is done by adding a little length and slowly increasing the depth inferiorly, gauging clinical success by the lack of snoring. The pace of addition is based on the comfort/tolerance of the patient with each addition.

The most efficient and precise method of increasing tail size is provided by one of dental radiology’s new diagnostic tools, 3-D cone beam. 3-D imaging allows detailed viewing of appliance tail placement, tongue position, and the size of the airway. It also makes precise adjustments possible to maximize the airway opening. We can easily analyze how and where we should add acrylic to the tail to maximize the opening of the airway. We are able to observe the original restricted airway, and then to see the improved airway with use of the FBS appliance. 3-D dental imaging clearly illustrates the ability of the appliance’s tail to control the tongue and open the airway (Figures 13 to 15).

|

| Figure 16. CASE 1: Upper left and right images: Pretreatment AHI of 33. Pretreatment frontal (left) view showing the narrow airway. Note the small oropharyngeal airway obvious in the lateral (right) view. Lower left and right images: Post-treatment AHI of 2 with FBS treatment. See increased oropharyngeal airway with tongue restrained by the tail of the FBS appliance. |

|

|

Figure 17a. CASE 2: Pretreatment AHI of 20.1. Note the narrow airway shown with both the frontal (left) and lateral (right) pretreatment views. |

|

|

Figure 17b. Post-treatment AHI of 2.4. Note the increased width of the airway in the frontal (left) and lateral (right) post-treatment views. |

|

| Figure 18. CASE 3: Upper left and right images: Pretreatment AHI 109.9. Frontal (left) and lateral (right) pretreatment views of airway appear good-sized. Lower left and right images: Post-treatment AHI of 22. Note airway opening has been dramatically improved using the FBS oral sleep appliance. |

CASE EXAMPLES: USINGTHE FBS ORAL APPLIANCE

CASE 1

A 31-year-old male patient presented with a history of severe snoring, moderate sleep apnea, and resulting fatigue. The patient had been previously treated with somnoplasty and an uvuloectomy, resulting in only minimal improvement. CPAP had been prescribed by the medical doctor, but the patient was found to be CPAP intolerant.

Treatment would consist of a pretreatment PSG (lab or hospital sleep test) to determine the Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI) (the number of times the oropharygeal airway is blocked by the tongue per hour), FBS oral appliance therapy, and a post-treatment AHI.

Including the initial visit, delivery appointment, and subsequent visits to adjust the appliance, treatment consisted of 5 appointments. It was successful in correcting the patient’s sleep problems. AHI went from 33 to 2. (See Figure 16 for the pre-and post-treatment images associated with this case.)

CASE 2

A 67-year-old male patient presented with snoring that was disturbing to his wife, and fatigue upon awakening. CPAP therapy had been previously prescribed by his medical doctor and he was found to be CPAP intolerant. Treatment would consist of a pretreatment PSG, FBS oral appliance therapy, and a post-treatment PSG.

Treatment involved 5 appointments and was successful. AHI went from 20.1 to 2.4. (See Figures 17a and 17b for the pre-and post-treatment images associated with this case.)

CASE 3

A 67-year-old male patient with a history of severe sleep apnea presented with fatigue and morning headaches. CPAP had been previously prescribed by a medical doctor, and the patient was very unhappy with it, still waking fatigued with morning headaches.

The patient wanted a FBS oral appliance to open the airway so he could reduce the high airflow setting of the CPAP device. Treatment would consist of a pretreatment PSG, a FBS oral appliance therapy with continued use of CPAP, and a post-treatment PSG.

In this case the lateral and frontal views of this patient’s airway appear good-sized. Pretreatment AHI was 109.9. (See Figure 18 for the pre- and post-treatment images associated with this case.) This patient’s sleep study showed that he stopped breathing 109.9 times an hour. Why? The real culprit in OSA reared its head in this case: the tongue was falling back 109.9 times an hour and blocking his airway.

Treatment success was achieved with the FBS appliance. The patient was very happy because he was able to reduce the CPAP airflow needed. His AHI went from a 109.9 (pretreatment) to 22 (post-treatment). This post-treatment AHI represented a large

reduction from the pretreatment AHI using an oral appliance.

DISCUSSION

In all 3 of the above cases, controlling the tongue resulted in increased airways and successful results. The oral appliance tail depressed the tongue and prevented the tongue from moving posteriorly to block the airway. This resulted in reduced AHI readings and the elimination of snoring. All 3 cases demonstrated an increase of the oropharygeal airway from the lateral view. In addition, we got a very pleasant surprise when we viewed the frontal view of the same airways: the lateral width of the 3 airways all increased with minimal advancement using the expanded tails of the FBS.

CONCLUSION

The best treatment available for OSA is CPAP therapy, but its rejection rate has been estimated by some to run as high as 75%. After weight loss, the best nonsurgical treatment for snoring/OSA is an oral appliance.

The FBS sleep appliance differs from other sleep appliances in that it has a posterior transpalatal/translingual bar and a Posterior Tongue Restrainer (tail). This controls and restrains the tongue in a manner that could not be previously achieved. In addition, utilizing 3-D imaging allows the dentist to view treatment progress and to make the appropriate changes to ensure clinical success. Utilizing these advanced oral and imaging techniques, dentistry can now realize success in treating snoring and OSA patients in the 99th percentile range, far beyond the low tolerance rates of CPAP, and well beyond the hit-and-miss success rate of the mandibular advancing technique.

In the author’s opinion, dentists are now able to offer an option for the treatment of snoring, mild to moderate OSA, and CPAP intolerance, that can dramatically improve the quality

and longevity of life for our patients.

References

- Kushida CA, Morgenthaler TI, Littner MR, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea with oral appliances: an update for 2005. Sleep. 2006;29:240-243.

- Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, eds. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2005:33-34.

- Mapes D. When happily ever after means separate beds. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2008/09/16/when-happily-ever-after-m_n_126810.html. Accessed July 26, 2009.

- Redline S, Adams N, Strauss ME, et al. Improvement of mild sleep-disordered breathing with CPAP compared with conservative therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(3 pt 1):858-865.

- Engleman HM, Kingshott RN, Wraith PK, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial of continuous positive airway pressure for mild sleep Apnea/Hypopnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:461-467.

- Millman RP, Rosenberg CL, Carlisle CC, et al. The efficacy of oral appliances in the treatment of persistent sleep apnea after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Chest. 1998;113:992-996.

Dr. Keropian is the founder of the Center for Snoring and Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) Intolerance, which provides nonsurgical treatment for patients who suffer wit mild or moderate sleep Apnea, CPAP-intolerance, and snoring. He can be reached at (818) 344-7200 or via e-mail at bk@cpapalternative.com or tmjrelief@msn.com.

Disclosure: Dr. Keropian is the inventor and patent holder of the Full Breath Solution sleep appliance, and CEO of Full Breath Corporation located in Tarzana, Calif.