Introduction

In treatment planning patient care, the initial focus is on disease control prior to definitive care. In edentulous patients, it is critical to improve the health of denture-bearing tissues prior to making impressions, especially in the clinical scenario when the patient is to have tissue-supported removable prostheses.1,2 Removable complete dentures, removable partial dentures, and tissue- and implant-supported overdentures fabricated on unhealthy tissues lead to further deterioration of tissue health and the compromise of prosthetic outcomes.1,3 Discrepancies in fit, tissue adaptation, stability, and occlusion can be attributed to the placement of a removable prosthesis on tissues that may have debris on them or have not been managed for proper intraoral hygiene. Patients who wear removable complete dentures are commonly affected by denture-associated pathologies such as stomatitis, Candida infection, traumatic sores, and/or denture-related hyperplasia.4 The capacity for healing and recovery of denture-bearing tissues is impacted by the presence of biofilm, plaque, calculus on the prosthesis, residual adhesive, irritation, and inflammation.5 To improve the potential for a successful patient outcome, thorough assessment and appropriate intervention are required for optimizing soft-tissue health.

The Importance of Overall Health

The improvement and maintenance of overall oral health is also important prior to the impression making, trial, and placement of a fixed prosthesis that may be tooth-supported or implant-supported.6-9 Increased bleeding and secretion of crevicular fluid (associated with inflamed tissues) makes it challenging to record the finish lines of the preparations/abutments, resulting in poor fit at the margins.9,10 It is not only the recording of the finish lines but also the trial and placement that are challenging in the presence of inflammation. Unhealthy gingival/peri-implant tissues are susceptible to recession,9-12 thereby affecting the aesthetics and oral hygiene maintenance of the definitive prosthesis.

Peri-implantitis

Peri-implantitis is one of the most frequent complications affecting the hard and soft tissues surrounding the implant, resulting in loss of implants.13-16 Poor plaque control is considered a key etiological factor in the development of periodontitis and peri-implantitis.17-20 Adequate plaque control is critical for the reduction of inflammation, limitation of pathogenic oral bacteria, and prevention of stains and odors.21 Unhealthy tissues affect the longevity and success of the teeth/implants and prostheses.22

Responsibility for Optimal Oral Hygiene Takes a Team Approach

Healthy and clean oral tissues are paramount during all phases of prosthesis fabrication.1 It is the responsibility of the entire dental team, including the assistants, hygienists, and the dentist, to educate, train and motivate the patient to improve and maintain oral health. The most efficient hygiene devices (manual and electric toothbrushes, brushing at least twice daily; interproximal brushes; flosses; antimicrobial rinses and gels; and subgingival irrigation systems) should be incorporated in the daily cleaning regimen of the patient.23-33 The practitioner can provide the cleaning aids to patients as soon as they accept their treatment plans. This is particularly advantageous because it ensures that the cleaning aids are immediately accessible to the patients and eliminates the possibility of getting the wrong products. The dental team should teach the use of the cleaning aids during the clinical appointment and not simply hand them over to the patient.

Toothbrushing (with a proper technique) aids in the mechanical removal of dental plaque, biofilm, calculus, food particles, and adhesive from the oral tissues34-36 and in massaging the oral tissues.37 An increase in blood flow, capillary permeability, and oxygenation; the promotion of keratinization of the gingival epithelium; a decrease in the gingival crevicular fluid volume, and an increase and enhancement of the proliferative activity of crevicular epithelial basal cells are the advantages associated with massaging/stimulation of the oral tissues.38-43 Electric toothbrushes/electric gum massagers aid in achieving the beneficial effects of tissue stimulation more quickly and efficiently compared to regular manual toothbrushes.44-46 A greater improvement in oral health and a reduction in plaque and gingivitis have been reported with powered (electric) toothbrushes when compared to manual toothbrushes.47-52 Electric toothbrushes are preferred by most patients because they are efficient, easy, and convenient to use.21

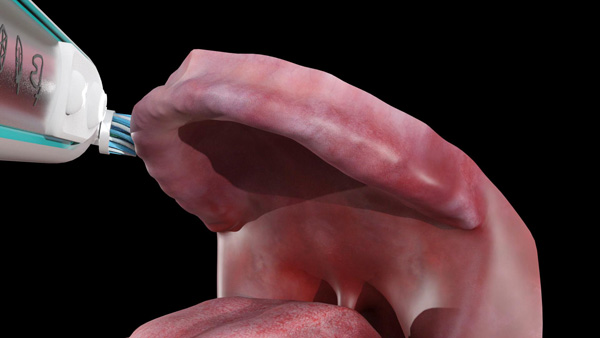

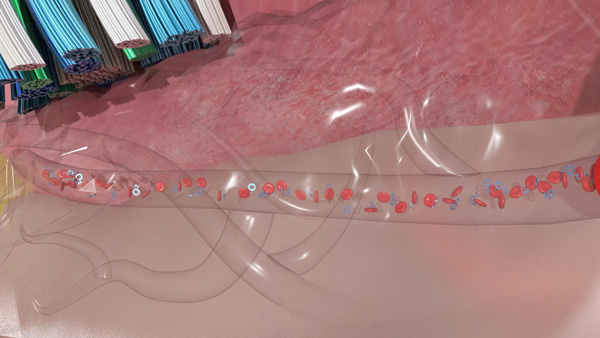

Recently, newer electric brushes (Genius [Oral-B]) with 3D cleaning action technology (oscillation, rotation, and pulsation), pressure sensors, position detection, and built-in timers have been introduced. The oscillating, rotating, and pulsating action of the electric toothbrush stimulates and massages the tissues, thereby increasing the velocity of red blood cells, which carry oxygen into the tissues. The use of electric toothbrushes for preventing peri-implantitis and maintaining peri-implant health has been discussed in several articles.34-36

Cleaning the Oral Cavity Before Clinical Procedures

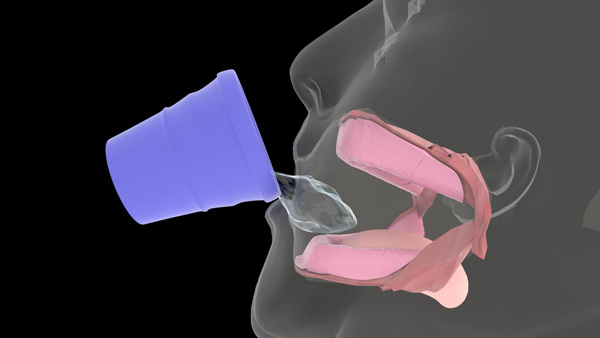

All patients should be instructed to clean their oral cavities in the dental office prior to all clinical procedures. The technique for edentulous patients is a little different compared to others. They are asked to sip warm water, hold it in the mouth, and secure it by pursing their lips. Pursing of the lips prevents the water from dripping out of the oral cavity while inserting the dual-action brush head (in the Daily Clean mode) into the mouth. The massaging action while water is in the mouth aids in increasing tissue hydration and improving tissue health. Daily home care for edentulous patients, dentate patients, and patients with implant prostheses is described below.

Daily Home Care for Edentulous Patients

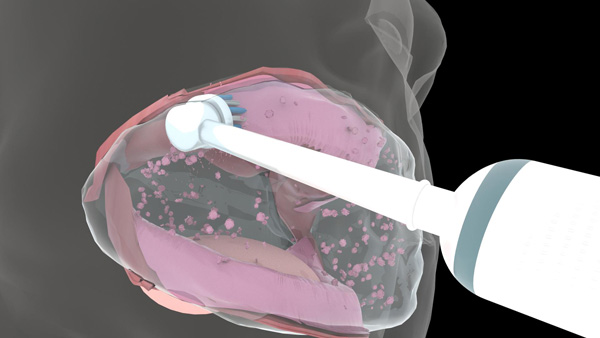

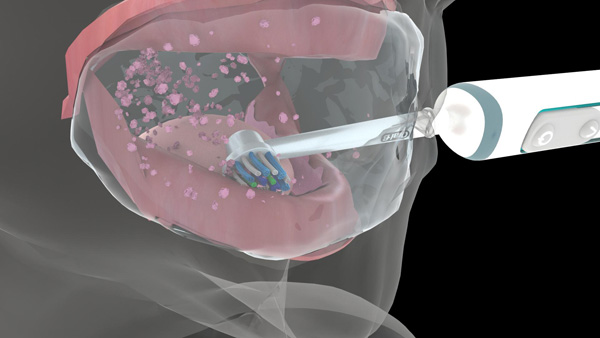

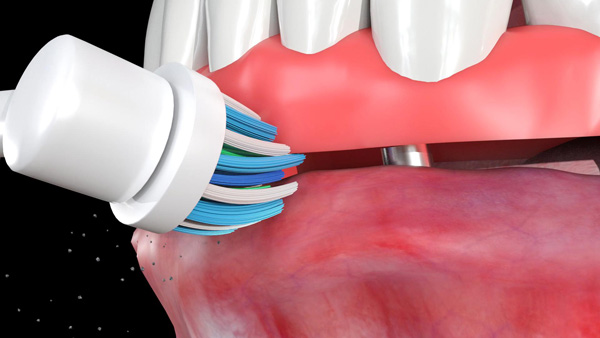

Edentulous patients are asked to place the brush in the mouth and gently move the brush head to contact all the tissue surfaces of the mouth (Figures 1a to 1c). They are instructed to use the electric toothbrush with the dual-action brush head (in Daily Clean mode) to clean and massage their oral tissues twice per day (Figure 1d) to maintain their oral health throughout their lives.

|

|

| Figure 1a. The Genius (Oral-B) positioned on the buccal surface of the maxillary denture-bearing tissues. | Figure 1b. The brush head positioned on the palatal surface of the maxillary denture-bearing tissues. |

|

|

| Figure 1c. The brush head positioned on the occlusal surface of the mandibular denture-bearing tissues. | Figure 1d. Massaging the oral tissues aids in increasing blood flow, capillary permeability, and oxygenation. |

Denture adhesive use is common among denture wearers. It is important to teach patients an effective method for adhesive removal from denture surfaces and oral tissues. Appropriate denture and oral hygiene should be accomplished by edentulous patients at least 2 times each day.

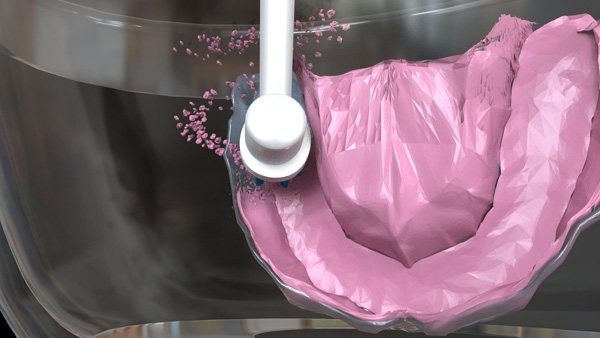

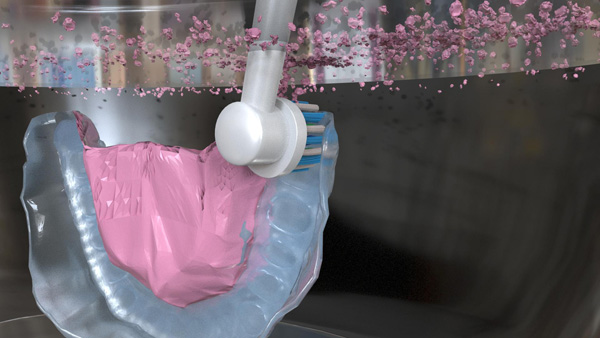

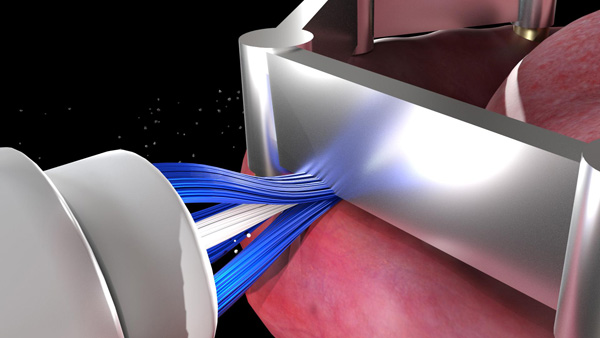

For removing biofilm, debris, and adhesive from the prosthesis, the patient is asked to submerge the prosthesis in a container filled with warm water. The patient is instructed to place the dual-action brush head (in Daily Clean mode) in the same container and slowly move it on the intaglio surface of the prosthesis (Figure 2a). Both the warm water and the oscillation-rotation-pulsation action of the brush aid in decoupling the biofilm, debris, and adhesive from the prosthesis (Figure 2b).

For removing biofilm, debris, and adhesive from the denture-bearing tissues, the patient is asked to sip warm water, hold it in the mouth, and secure it by pursing his or her lips (Figure 3a). Pursing of the lips prevents the water from dripping out of the oral cavity while inserting the toothbrush into the mouth. The patient is instructed to move the dual-action brush head slowly and gently on all the denture-bearing tissue surfaces. Both the warm water and the oscillation-rotation-pulsation action of the brush head aid in decoupling the biofilm, debris, and adhesive from the tissues (Figures 3b and 3c). Once all surfaces are clean, the patient is asked to expectorate.

|

|

| Figure 2a. The patient moves the brush head slowly and gently on the intaglio surface of the maxillary denture. | Figure 2b. Separation of biofilm, debris, and adhesive from the maxillary denture. |

|

|

| Figure 3a. The patient is asked to sip warm water, hold it in the mouth, and secure it by pursing their lips. | Figure 3b. Separation of biofilm, debris, and adhesive from the maxillary tissues. |

Daily Home Care for Dentate Patients, Patients With Fixed Dental Prostheses, and Patients With Implant-Retained Fixed Dental Prostheses

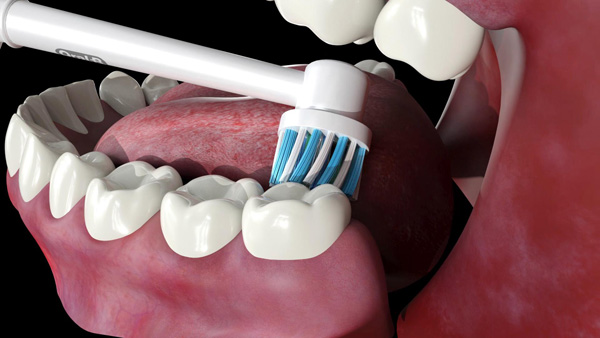

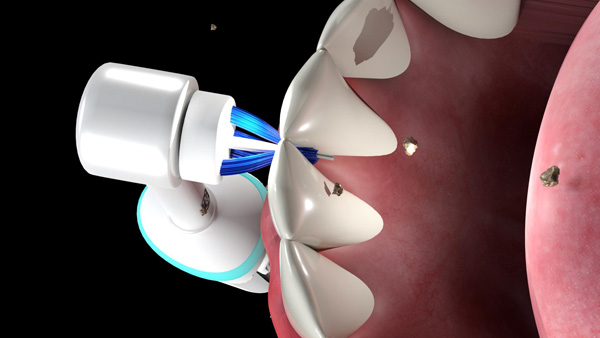

These patients are advised to place the cross-action brush head (in Daily Clean mode) in the mouth and gently move the brush head to contact all the surfaces of the teeth/prosthesis in the mouth (Figures 4a and 4b) and the gingival tissues (Figure 4c). This enables the cleaning of the lingual, labial/buccal, and incisal/occlusal surfaces of the teeth/prosthesis and massaging of the gingiva. For sensitive teeth and gums, it is recommended to use the sensitive brush head in the Sensitive mode. The oscillation-rotation-pulsation action of the brush aids in removing stubborn debris. The interproximal brush head in Daily Clean mode is recommended for interproximal cleaning (Figure 5a) and cleaning under the surfaces of pontics/prostheses(Figures 5b and 5c). This will permit the removal of biofilm, plaque, and food particles accumulated in these spaces.

|

|

| Figure 3c. Separation of biofilm, debris, and adhesive from the mandibular tissues. | Figure 4a. The Genius positioned on the palatal/lingual surfaces of the natural teeth. |

|

|

| Figure 4b. The brush head positioned on the occlusal/incisal surfaces of a fixed dental prosthesis. | Figure 4c. The brush head positioned at the junction of the implant-supported fixed complete denture and the tissues. |

|

|

| Figure 5a. The Genius interproximal brush head positioned for use in interdental cleaning. | Figure 5b. The interproximal brush head positioned between the pontic and the tissues. |

|

|

| Figure 5c. The interproximal brush head positioned between the prosthesis and the tissues. | Figure 6a. The Genius cross-action brush head being used to clean all the surfaces of the bar. |

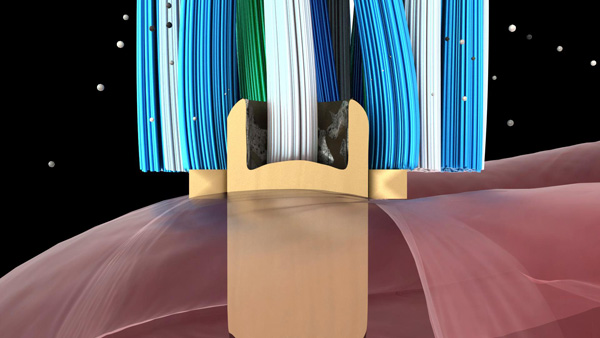

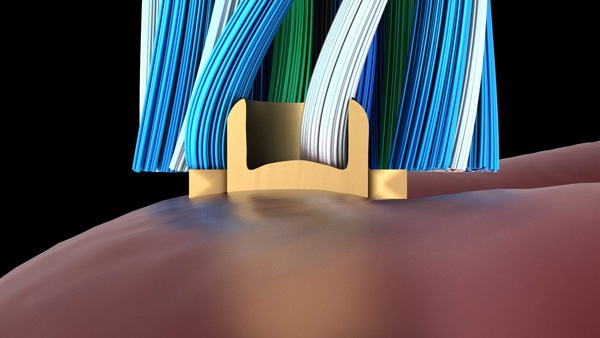

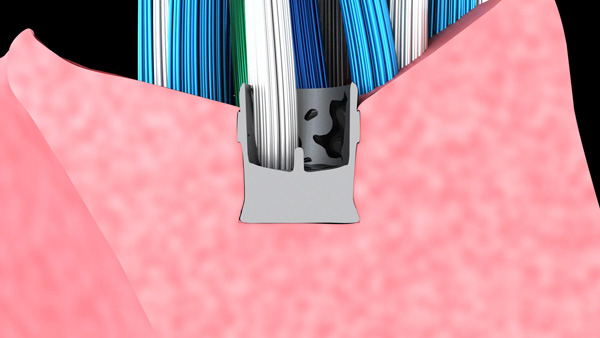

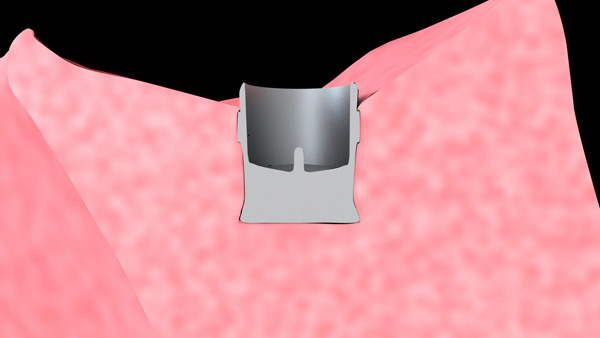

Daily Home Care for Patients With Removable Implant Prostheses

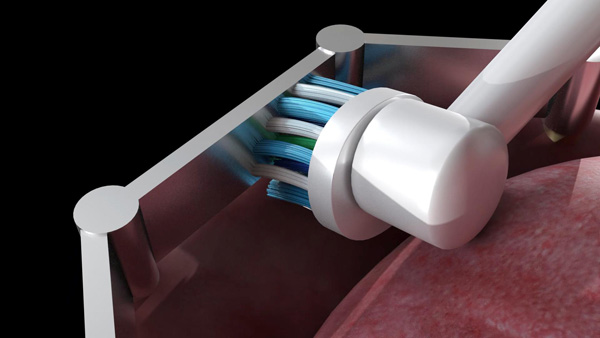

Patients with removable implant prostheses supported by an implant bar attachment are asked to place the cross-action brush head in the mouth and rotate the brush to gently clean all tissue surfaces. The patient is instructed to position the bristles on the implant bar and gently move the brush head to contact all the surfaces of the bar. The oscillation-rotation-pulsation of the brush aids in removing stubborn debris from the buccal, lingual (Figure 6a), occlusal, and intaglio surfaces of the bar. The interproximal brush head in Daily Clean mode is recommended for cleaning the intaglio surface of the bar. The patient is instructed to gently guide the bristle head between the bar and the tissue with gentle pressure (Figure 6b). Move the brush head laterally to clean the entire area. This will permit the removal of biofilm, plaque, and food particles that have accumulated underneath the bar. For cleaning the stud attachment, the patient is instructed to position the bristles on the stud attachment and apply gentle pressure. Maintaining the vertical positioning not only aids in removing debris surrounding the stud abutments but also ensures that the bristles engage the apertures in the stud abutments and remove any impacted debris (Figure 7). Debris can accumulate in and around the retentive element of the stud attachment/bar in the prosthesis and affect the retention and stability of the prosthesis. The patient is asked to place the cross-action brush on the retentive elements of the stud attachment/bar and apply gentle pressure to remove debris within and around the retentive element (Figure 8).

|

|

| Figure 6b. The interproximal brush head positioned between the bar and the tissues. | Figure 7a. Debris being detached from the stud attachment. |

|

|

| Figure 7b. Clean stud attachment, | Figure 8a. Debris being detached from the retentive element. |

|

|

| Figure 8b. Clean retentive element. |

Acknowledgment: All graphics in this article were created by Dr. Massad.

REFERENCES

1. Massad JJ, Cagna DR, Goodacre CJ, et al. Definitive impressions. In: Massad JJ, Cagna DR, Goodacre CJ, et al. Application of the Neutral Zone in Prosthodontics. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2017:35-50.

2. Babiuc I, Păuna M, Maliţa MA, et al. Correct complete denture rehabilitation, a chance for recovering abused tissues. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2009;50:707-712.

3. Keubker WA. Denture problems: causes, diagnostic procedures and clinical treatment. I. Retention problems. Quintessence Int Dent Dig. 1984;15:1031-1044.

4. Bloem TJ, Razzoog ME. An index for assessment of oral health in the edentulous population. Spec Care Dentist. 1982;2:121-124.

5. Felton D, Cooper L, Duqum I, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the care and maintenance of complete dentures: a publication of the American College of Prosthodontists. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(suppl 1):1S-20S.

6. Christensen GJ. Laboratories want better impressions. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:527-529.

7. Hess L. The biologic and restorative interface: improving periodontal health with contemporary materials and sound restorative dentistry. Contemporary Esthetics and Restorative Practice. 2005;9:46-51.

8. Caffesse RG, Guinard EA. Treatment of localized gingival recessions. Part IV. Results after three years. J Periodontol. 1980;51:167-170.

9. Cranham JC. Making accurate master impressions: Guidelines for predictably capturing the detail and occlusal morphology the laboratory needs to create successful crown-and-bridge restorations. Inside Dentistry. 2012;8:62-68.

10. Terry DA, Leinfelder KF, Lee EA, et al. The impression: a blueprint to restorative success. Inside Dentistry. 2006;2:66-71.

11. Lee EA. Impression material selection in contemporary fixed prosthodontics: technique, rationale, and indications. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2005;26:780-789.

12. Donovan TE, Cho GC. Soft tissue management with metal-ceramic and all-ceramic restorations. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1998;26:107-112.

13. Zitzmann NU, Berglundh T. Definition and prevalence of peri-implant diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(suppl 8):286-291.

14. Roos-Jansåker AM, Renvert H, Lindahl C, et al. Surgical treatment of peri-implantitis using a bone substitute with or without a resorbable membrane: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:625-632.

15. Smeets R, Henningsen A, Jung O, et al. Definition, etiology, prevention and treatment of peri-implantitis—a review. Head Face Med. 2014;10:34.

16. Atieh MA, Alsabeeha NHM, Faggion CM Jr, et al. The frequency of peri-implant diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2013;84:1586-1598.

17. Ramanauskaite A, Tervonen T. The efficacy of supportive peri-implant therapies in preventing peri-implantitis and implant loss: a systematic review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Res. 2016;7:e12.

18. Szkaradkiewicz KA, Karpinski MT. Microbiology of chronic periodontitis. Journal of Biology and Earth Sciences. 2013;3:14-20.

19. Ericsson I, Berglundh T, Marinello C, et al. Long-standing plaque and gingivitis at implants and teeth in the dog. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1992;3:99-103.

20. Salvi GE, Aglietta M, Eick S, et al. Reversibility of experimental peri-implant mucositis compared with experimental gingivitis in humans. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23:182-190.

21. Cagna DR, Massad JJ, Daher T. Use of a powered toothbrush for hygiene of edentulous implant-supported prostheses. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2011;32:84-88.

22. Lee EA. Predictable elastomeric impressions in advanced fixed prosthodontics: a comprehensive review. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1999;11:497-504.

23. de Araújo Nobre M, Cintra N, Maló P. Peri-implant maintenance of immediate function implants: a pilot study comparing hyaluronic acid and chlorhexidine. Int J Dent Hyg. 2007;5:87-94.

24. Humphrey S. Implant maintenance. Dent Clin North Am. 2006;50:463-478, viii.

25. Renvert S, Lessem J, Dahlén G, et al. Topical minocycline microspheres versus topical chlorhexidine gel as an adjunct to mechanical debridement of incipient peri-implant infections: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:362-369.

26. Horwitz J, Machtei EE, Zuabi O, et al. Amine fluoride/stannous fluoride and chlorhexidine mouthwashes as adjuncts to single-stage dental implants: a comparative study. J Periodontol. 2005;76:334-340.

27. Sarment DP, Peshman B. Manual of Dental Implants: A Reference Guide for Diagnosis & Treatment. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp; 2004:70-73.

28. Tawse-Smith A, Duncan WJ, Payne AG, et al. Relative effectiveness of powered and manual toothbrushes in elderly patients with implant-supported mandibular overdentures. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:275-280.

29. Truhlar RS, Morris HF, Ochi S. The efficacy of a counter-rotational powered toothbrush in the maintenance of endosseous dental implants. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:101-107.

30. Vandekerckhove B, Quirynen M, Warren PR, et al. The safety and efficacy of a powered toothbrush in patients with implant-supported fixed prostheses. Clin Oral Investig. 2004;8:206-210.

31. Wolff L, Kim A, Nunn M, et al. Effectiveness of a sonic toothbrush in maintenance of dental implants. A prospective study. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:821-828.

32. Felo A, Shibly O, Ciancio SG, et al. Effects of subgingival chlorhexidine irrigation on peri-implant maintenance. Am J Dent. 1997;10:107-110.

33. Ciancio SG, Lauciello F, Shibly O, et al. The effect of an antiseptic mouthrinse on implant maintenance: plaque and peri-implant gingival tissues. J Periodontol. 1995;66:962-965.

34. Allocca G, Pudylyk D, Signorino F, et al. Effectiveness and compliance of an oscillating-rotating toothbrush in patients with dental implants: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Implant Dent. 2018;4:38.

35. Massad J, Verma M, Ahuja SA. Electric toothbrushes for preventing periodontitis and peri-implantitis. Dental Practice. 2019;16:53-56.

36. Massad J, Verma M, Ahuja S. Improving implant survival by implementing the use of an electric toothbrush. Dent Today. 2019;38:68-79.

37. Pader M. Oral Hygiene Products and Practice. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1988:141-194.

38. Caffesse RG, Nasjleti CJ, Kowalski CJ, et al. The effect of mechanical stimulation on the keratinization of sulcular epithelium. J Periodontol. 1982;53:89-92.

39. Mackenzie IC. Does toothbrushing affect gingival keratinization? Proc R Soc Med. 1972;65:1127-1131.

40. Brill N. Influence of capillary permeability on flow of tissue fluid into gingival pockets. Acta Odontol Scand. 1959;17:23-33.

41. Hanioka T, Nagata H, Murakami Y, et al. Mechanical stimulation by toothbrushing increases oxygen sufficiency in human gingivae. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:591-594.

42. Kroone H, Maeda T, Stoltze K, et al. Effect of toothbrush stimulation on temperature of gingival and alveolar mucosae. J Oral Rehabil. 1980;7:97-102.

43. Tautin FS. The beneficial effects of tissue massage for the edentulous patient. J Prosthet Dent. 1982;48:653-656.

44. Tomofuji T, Kusano H, Azuma T, et al. Gingival cell proliferation induced by use of a sonic toothbrush with warmed silicone rubber bristles. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1636-1639.

45. Matsumoto A. Evaluation of usefulness of self-made electronic device for gingival massage. Part I: Effects on changes of gingival blood flow. The Journal of Japan Society for Dental Hygiene. 2008;3:35-40.

46. Kapur K, Shklar G. Effects of a power device for oral physiotherapy on the mucosa of the edentulous ridge. J Prosthet Dent. 1962;12:762-769.

47. Robinson PG, Deacon SA, Deery C, et al. Manual versus powered toothbrushing for oral health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD002281.

48. Rosema NA, Timmerman MF, Versteeg PA, et al. Comparison of the use of different modes of mechanical oral hygiene in prevention of plaque and gingivitis. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1386-1394.

49. Kurtz B, Reise M, Klukowska M, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing plaque removal efficacy of an oscillating-rotating power toothbrush to a manual toothbrush by multiple examiners. Int J Dent Hyg. 2016;14:278-283.

50. Kulkarni P, Singh DK, Jalaluddin M. Comparison of efficacy of manual and powered toothbrushes in plaque control and gingival inflammation: a clinical study among the population of East Indian region. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2017;7:168-174.

51. Jain Y. A comparison of the efficacy of powered and manual toothbrushes in controlling plaque and gingivitis: a clinical study. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2013;5:3-9.

52. Yaacob M, Worthington HV, Deacon SA, et al. Powered versus manual toothbrushing for oral health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(6):CD002281.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Massad is an associate professor in the department of graduate prosthodontics at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC) College of Dentistry in Memphis; a clinical professor at the University of Oklahoma College of Dentistry in Oklahoma City; an associate faculty at the Tufts University School of Dental Medicine in Boston; an adjunct associate faculty in the department of comprehensive dentistry at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UT Health San Antonio) School of Dentistry; and an adjunct professor in the department of restorative dentistry at Loma Linda University in Loma Linda, Calif. He has a private practice in Tulsa, Okla. He can be reached at joe@joemassad.com.

Dr. Garcia is dean and a professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas School of Dental Medicine. She was in private practice in Denver early in her career, then served as faculty at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center School of Dentistry, as the department chair of prosthodontics at UT Health San Antonio, and as professor and associate dean for education at the University of Iowa College of Dentistry. She can be reached at lily.t.garcia@unlv.edu.

Dr. Ahuja worked at UTHSC in Memphis as an assistant professor in the department of prosthodontics for 3 and a half years. She has lectured nationally and internationally on various prosthodontic topics at various dental conferences. She has more than 50 publications in peer-reviewed national and international journals and is also the co-author of the textbook Applications of the Neutral Zone in Prosthodontics. She is a consultant scientific writer and a consulting prosthodontist for several private dental clinics in Mumbai, India, and also for NYU Langone Medical Center in New York. She can be reached via email at swatiahuja@gmail.com.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Massad consults with P&G. Drs. Garcia and Ahuja report no disclosures.

RELATED ARTICLES

Evidence-Based Treatment for the Edentulous Patient