Researchers at the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) have catalogued 120,000 oral mucosa cells by type and function. The NIDCR believes this cell atlas will serve as a detailed community resource to help researchers answer key questions about oral biology and disease.

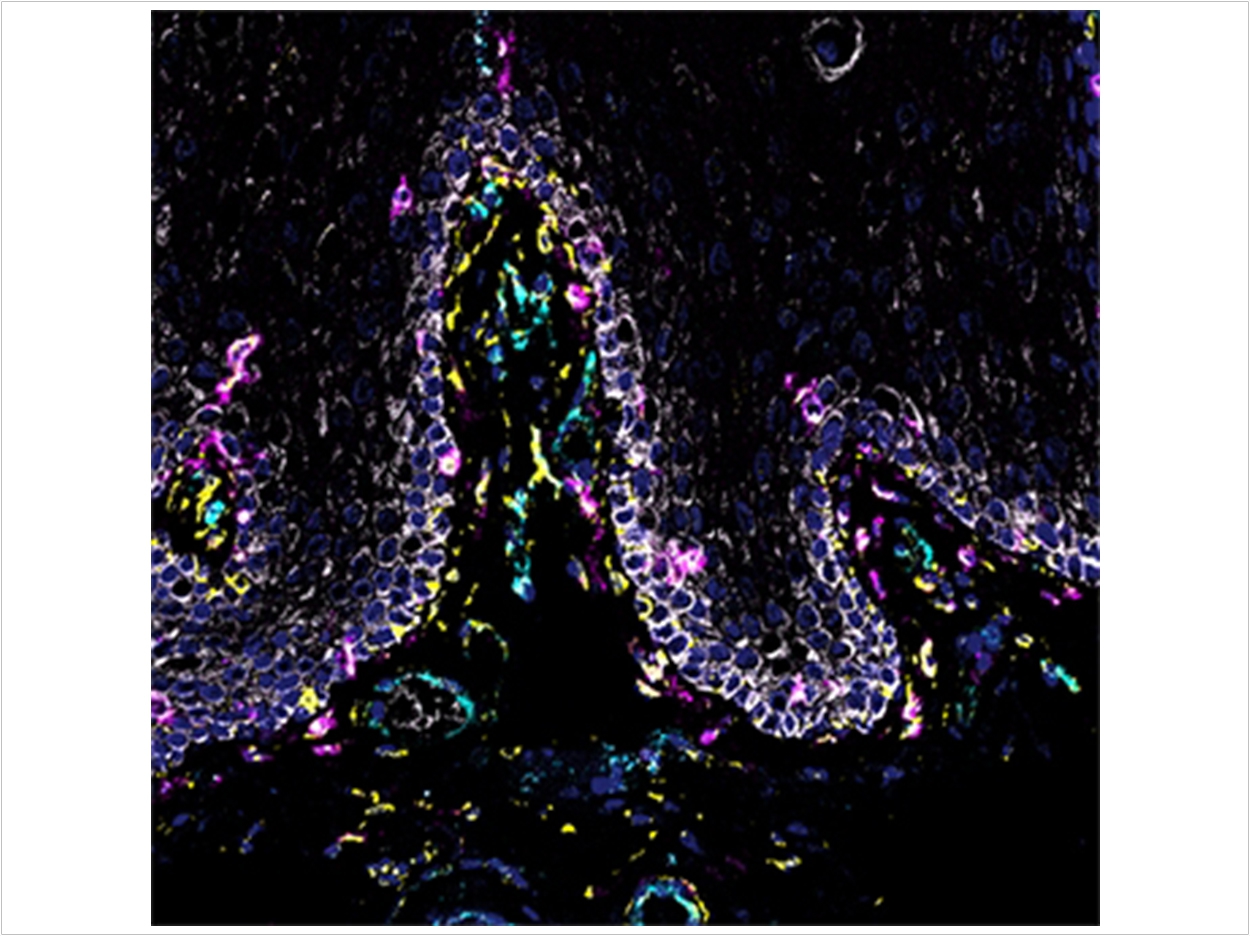

The NIDCR’s researchers conducted a census of oral mucosal cells from gum and inner cheek tissues of people with and without severe periodontitis. By analyzing gene expression cell by cell, they were able to catalog cells by type and function and reveal a previously unknown role for connective tissue cells in orchestrating immune responses linked to periodontitis.

“There’s been a huge international effort to create a cell by cell atlas of the human body,” said senior author Niki Moutsopoulis, DDS, PhD, a principal investigator at NIDCR.

That initiative, the Human Cell Atlas, was launched in 2016 and is led by scientists at the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, United Kingdom.

“We wanted to do our part by contributing data from the oral mucosa,” said Moutsopoulos.

The oral mucosa is composed of four main types of cells. Epithelial cells form the surface layer, while endothelial cells line the blood vessels that supply nutrition and oxygen. Stromal cells give structure to the mucosa, and immune cells survey the surroundings to capture and destroy foreign particles.

However, Moutsopoulos and her colleagues performed a deeper dive, the NIDCR said, identifying distinct subpopulations with unique traits and functions among the four cell types. One type of stromal cell, called fibroblasts, caught the researchers’ attention.

“The most striking part of the study was the prominent immune signature of fibroblasts in the oral environment,” said Moutsopoulos. “We usually think of stromal cells, such as fibroblasts, as mere producers of connective tissue. But our analyses suggest that they also play a role in immune function, particularly related to recruiting neutrophils.”

Neutrophils are immune cells that migrate into the oral cavity to defend us against pathogens and are thought to play a protective role against periodontitis. In fact, the NIDCR said, genetic deficiencies in neutrophil recruitment are linked to severe periodontitis. But neutrophils also are known to over-congregate in the gums of people with common forms of periodontitis.

Gene expression data from the new study suggests that stromal cells are wired to induce inflammatory responses and send signals that recruit neutrophils in healthy people. The same stromal cells appear to become over-activated in periodontitis, resulting in an exaggerated immune response that could contribute to disease progression.

“This new piece of information is one of the many insights that can be gleaned from the oral cell catalog,” said first author Drake Williams, DDS, PhD, a clinical research fellow at NIDCR.

“Another opportunity afforded by this atlas is that we were able to map the expression of genes linked to periodontitis susceptibility at the cell level, within the oral tissues. We envision that this information will provide clues towards understanding cell-specific functions that mediate periodontitis pathogenesis in different subsets of patients,” said Williams.

The oral cell catalog also can be used to understand oral diseases beyond periodontitis, NIDCR said. The data from healthy volunteers, who were carefully screened for oral and systemic health, serves as a baseline that can be compared against other disease states.

The researchers have contributed their cell atlas to the oral and craniofacial network of the Human Cell Atlas project. They plan to expand the catalog to include cells from patients with inherited forms of oral mucosal diseases.

“The study provided an opportunity to view the oral mucosa through a new lens,” said Moutsopoulos. “We really enjoyed putting it together and had fantastic colleagues that contributed to this effort.”

The study, “Human Oral Mucosa Cell Atlas Reveals a Stromal-Neutrophil Axis Regulating Tissue Immunity,” was published by Cell.

Related Articles

Better Gum Disease Prevention Could Save Billions in Healthcare Costs

Another Study Confirms Link Between Alzheimer’s and Gum Disease

Therapies Put the Body’s Own Repair Processes to Work in Regenerating Bone