Researchers at the University of Otago Faculty of Dentistry in New Zealand are developing new tooth-capping technology designed to replace the common metal material that’s currently used on kids’ teeth when they visit public dental services.

These caps can be fit over decayed teeth without any surgical intervention, the researchers said, making them a convenient and idea choice for treating children with tooth decay.

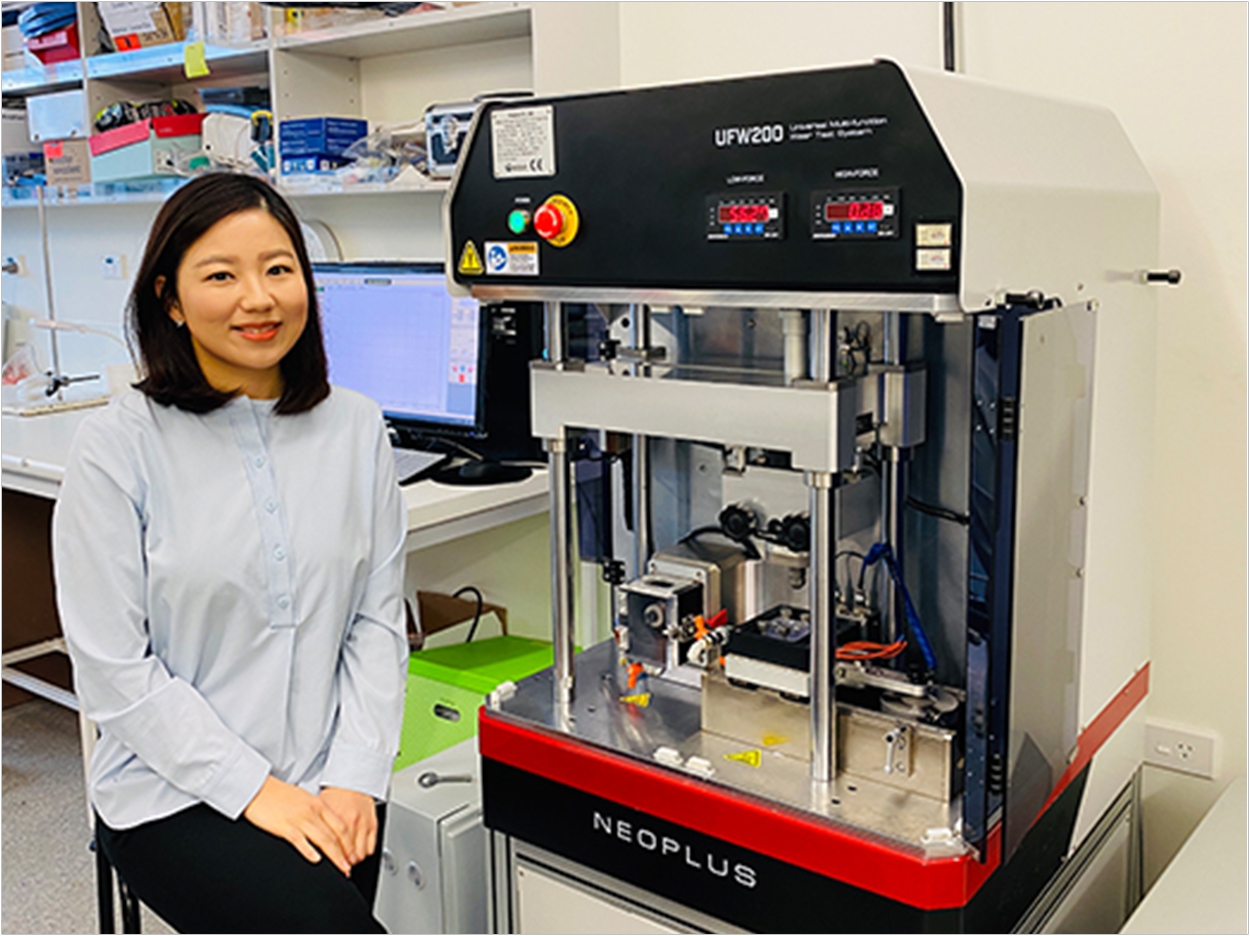

Traditional metal caps don’t suit some children. They’re preformed, and while they come in different sizes, Māori and Pacific children’s teeth often are bigger than the preformed models, according to lead researcher Dr. Joanne Choi.

The metal caps’ appearance also can be an issue since they are far more noticeable, Choi said, highlighting the fact that children who have them have tooth decay. This compounds the dental anxiety that many children feel as well, discouraging dental treatment, Choi added.

“Oral health is a big problem in New Zealand and internationally, and dental anxiety is a real thing. So if we can come up with a treatment that can help reduce that, that’s going to be good for a lot of people,” Choi said.

Tooth-colored crowns already exist for adults, but in many cases they are unsuitable or unavailable for publicly funded oral healthcare for children, Choi said.

“The novel crowns we’re developing will actually be more cost-effective for the District Health Boards, compared to the investment currently made on the metal caps. This is important because it will lead to the treatment of many more patients,” said Choi.

Besides, for the kids and parents, the aesthetic factor, having tooth-colored caps, is really important,” Choi said, adding that her research began almost by chance in 2017 when she was inspired at a seminar by then University of Otago associate professor Lyndie Foster Page.

“I was listening to one of her research seminars, and she mentioned how parents had said the metal crowns don’t look nice. If the kids have one or two metal crowns, it’s not such a problem. But if they have three or four, it becomes noticeable,” Choi said.

“Whānau (extended families) had said that metal caps may highlight that their tamariki (children) have ‘bad teeth,’ which Dr. Foster Page said may emphasize oral health inequalities since the metal crowns lead to stigmatizing poor oral healthcare,” Choi said.

“So I thought that maybe I could come up with a new material that works like the metal crowns and is affordable, but looks like the tooth-colored crowns. Altogether much more aesthetic,” Choi said.

The researchers initially worked closely with a Korean manufacturer, but they are now working with a Dunedin manufacturer.

Technical and commercial pathway details are still in development, but Choi expects that the data already gathered will accelerate the next phase of the project. As a result, the new caps could be on the shelf an in children’s mouths in a few years.

The next step is ensuring the new caps are better suited to Kiwi kids’ teeth, in particular Māori and Pacific children between the ages of 4 and 7. Choi is working with the University of Otago’s Dunedin dental school, where parents will have the option of getting their children’s teeth scanned using a digital oral scanner. The scans will take an extra 5 to 10 minutes.

This work has been largely enabled by a follow-up grant recently announced by Cure Kids, which runs until July 2021. Cure Kids initially funded this project via an Innovation Seed Fund grant in 2018.

By the end of next year, Choi said, a prototype will be ready for clinical trials, which will likely run for one to two years. She then expects the final product to be commercialized, first in New Zealand and then internationally.

Choi said that the journey from having her interest piqued in a seminar to now being within reach of the product being commercially available for children has been a long one.

“When I started, I never thought it would take this long. The development stage does take time, but I’ve learned so much through this process. I’m going to make it work, 100%,” she said.

“There were times when I almost wanted to give up, but so many people have helped me through the process,” Choi said. “I believe that we can develop the new dental crown system to help kids, families, and social well-being. This is a collaborative process, and I feel really lucky to have had so much support. So, I’ll make it work.”

Related Articles

Cariology Research Projects Receive 200,000 Euros in Grant Funding

Australian Dental Association Initiative Teaches Kids About Oral Health and Nutrition

Celebrate World Cavity-Free Future Day on October 14