In 2018, Netflix and other digital platforms began streaming a documentary called Root Cause that made claims about the safety of root canal treatment.1 Though Netflix has since pulled the title from its offerings, the movie is still available elsewhere, and the claims continue to resonate online, along with an active community of understandably concerned patients.

In a contrasting position, professional societies have issued position statements, letters to content distrubutors, and talking points in an effort to reassure the public.2,3 Yet the positions of the documentary’s producers and those of these societies fall short on accuracy, scientific integrity, transparency, and honesty. A key error in critical thinking undermines all of their arguments.

As the microbiological claims are a central point of contention, we will review a more modern understanding of microbiology and microbial dormancy. We will also give practicing clinicians several talking points for discussing this information with patients, along with guidelines for treating patients who are understandably concerned and confused.

In a central example, the documentary reports that 98% of women who have breast cancer had a root canal tooth on the same side as their breast cancer. 1,21 This statement, if true, sounds like a cause for concern if not alarm given the tens of millions of root canals performed each per year.

“People present things correctly, but they are stating it in ways to make you misunderstand,” said noted epidemiologist Sander Greenland, DrPH, MS.4

Inconsistent Statements

The American Association of Endodontists (AAE), and the American Association for Dental Research (AADR) released a joint statement condemning the movie and its findings. Yet a closer look at that statement does give one pause.

“Approximately 25 million new endodontic treatments, including root canals, are performed safely and effectively each year. Root canal treatment eliminates bacteria from an infected tooth, prevents reinfection of the tooth, and saves the natural tooth,” the statement read.2

The European Society for Endodontology (ESE) also responded to the movie.

“There is universal agreement in the scientific and clinical communities that root canal treatment is an effective and predictable cure for pulp and periapical infections. In fact, it represents one of the best-documented and safest procedures for preventing and curing oral infections, and thus prevent and treat rather than cause systemic complications. Current scientific and clinical evidence have clearly shown the advantages, safety and value of root canal treatment,” the ESE said in its statement.3

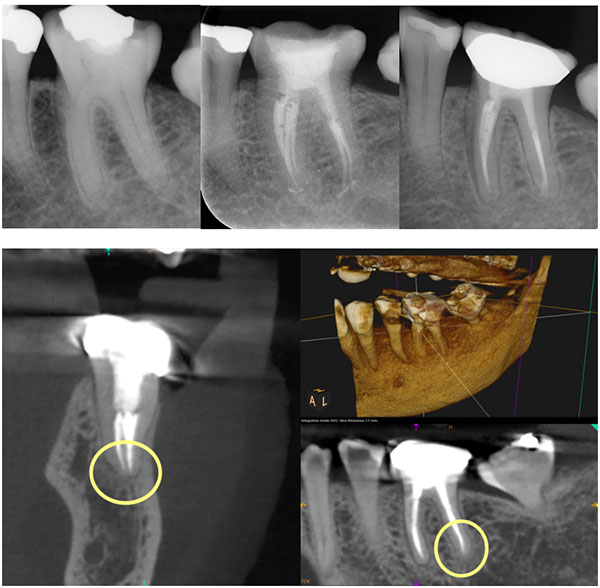

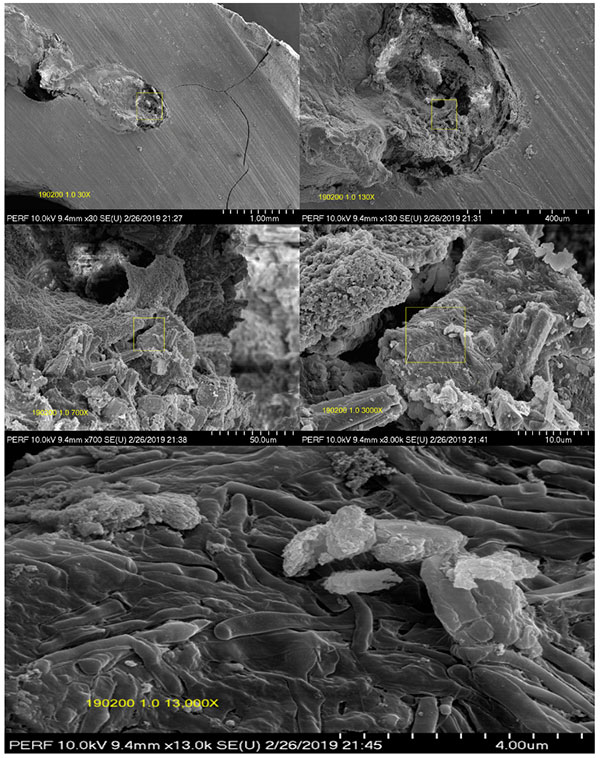

In fact, decades of research show the nearly ubiquitous presence of bacteria after endodontic treatment, along with an abundant body of work on post-treatment disease (Figures 1 and 2). As this research is readily available to our patients on the Internet, and given that this research contradicts these statements from our professional associations, what would a reasonable person think of our reassurances that endodontic treatment is safe?

“I guarantee it does not reinforce their confidence in your un-biasedness in regard to the advice you give them,” said Greenland.4

In other words, trust is broken.

|

| Figure 1. This long-term, asymptomatic case included biofilm in the canal system. The preop (top, left), postop (top, middle), and 15-year follow-up (top, right) projection radiographs show no evidence of apical periodontitis on the distal root, though the mesial root is fractured. The 15-year CBCT followup also shows normal periapical architecture (bottom). |

|

|

Figure 2. The SEM view of the apical third of the sectioned distal root revealed bacterial profiles observed at many levels (top and middle). The SEM view of the canal wall showed extensive biofilm profiles, in this case appearing “healed” with both projection radiography and CBCT (bottom). |

Our own research renders these statements from our professional organizations patently and demonstrably false. Unfortunately, our professional associations have not presented things correctly and are misstating the facts of the issue, bordering on dishonesty. These kinds of mischaracterizations are harmful and only serve to fan the flames of distrust and undermine any evidence and reassurance we might offer.

According to noted cognitive scientist and researcher Gerd Gigerenzer, PhD, of the Harding Center for Risk Literacy, “research has demonstrated that the problem lies less in stable cognitive deficits than in how information is presented to physicians and patients. This includes biased reporting in medical journals, brochures, and the media that uses relative risks and other misleading statistics, motivated by conflicts of interest and defensive medicine that do not promote informed physicians and patients.”5

Who Is Right? The Error in Critical Thinking

There is no shortage of undergraduate and graduate courses in decision-making and critical thinking skills. After graduation, there continue to be academic articles and presentations at national meetings on the topic. Yet the core skills in critical thinking that are obvious once exposed escape clinicians, educators, researchers, and patients alike.

We briefly introducte these issues in Advanced CBCT for Endodontics6 and will introduce a central critical error that has pervaded endodontic thinking for decades, as well as the case presentation of breast cancer in Root Cause noted above. Consider the following example:

- The probability of being an American, given that one is President, is 100%.

- The probability of being the President, given that one is American, is 0.0000003% (one in 300 million)

Or:

- The probability of being a human, given that one is a woman, is 100%.

- The probability of being a woman, given that one is a human, is 50%.

In contrast:

- The probability of a positive mammogram given that one has breast cancer is 80%.

- What is the probability of breast cancer given that one has a positive mammogram?

(Generally speaking, this conditional probability problem is not even recognized as not having enough information to actually solve it. In the pure screening example where we may set prevalence of breast cancer at 1%, the probability of having cancer, given that one has a positive screening, is only about 10%, not 80%. This is given by Bayes’ Theorem.)

These are conditional probability problems, as is the problem with root canals and breast cancer cited in Root Cause. In the first two examples above, as the answers are known, the problems generally aren’t recognized as conditional probability problems. However, the form of the problems in the breast cancer example is identical, yet the second probability is not known. Instead, a seemi

ngly plausible estimate of 80% is substituted or, in Root Cause, 98%.

As the form of the problem is not recognized as a conditional probability problem, this substitution is done by physicians, dentists, and patients alike. Conditional probability problems are not well interpreted by humans. Daniel Kahneman, PhD, won a Nobel Prize in economics by clarifying just how pervasive the problems are with conditional probability in human reasoning, and this includes scientists!

Problems in conditional probability attempt to provide an estimate of the probability of an event in the light of a prior event having already occurred (or is known to be true with certainty). In mathematical terms, it is written as:

P[A] | [B]

This is read as“The probability of A, given that event B has already occurred or is known to be true.”

We say the probability estimate of event A is conditioned upon an event B that we know is true. To use our President/citizen example, the probability of being the President of the United States (A), given that event B (that of being a citizen) has occurred or we know is true, can be calculated with no error if, in fact, we know event B is true with 100% certainty.

In the endodontic domain, we might express the conditional probability as the probability of bacteria being present in the pulp space, given that apical periodontitis (AP) is already known to have occurred. Mathematically, this is expressed as:

P [bacteria] | [AP is present]

or in general terms:

P [of an observation of bacteria] | [disease is known to be present]

Our problem as clinicians is not that we don’t understand some conditional probabilities. They can be as easy to understand as the President/citizen probability. Our problem comes when the conditional probability is reversed. What is the probability of disease given that bacteria are known to be present?

P [disease] | [we know bacteria are present]

This probability is not so obvious and, indeed, requires some very careful, analytical thinking to avoid error and the cognitive illusion that accompanies this error.

It is a sad fact that problems with conditional probability reasoning pervade the endodontic evidential base and have for decades. Unfortunately, this is not the only problem. Other, even more basic problems in formal logic are also quite common.

Modes of Reasoning

These issues have to do with our mode of reasoning, the classification of which was first made by Aristotle in 350 BC in his Organon.7 Our reasoning mode, which of necessity has to be different in the life sciences, means that probabilities like our President/citizen example cannot be used. For example, if one is President, we can maintain, with 100% certainty, that such a person is a US citizen. Such certainty can be made because it uses two “strong” deductive syllogisms:

If A is true, then B is true.

A is true

______________________________

therefore, B is true

And its inverse (contrapositive):

If A is true, then B is true.

B is false

______________________________

therefore, A is false

It is known that to be a President [A], you must be a citizen [B]. Therefore, if you are President [A], we know that you are a citizen [B]. If you are not a citizen [B is false], we know you are not President [A is false].

So with “strong” syllogisms, inverting the conditional is seldom a problem. The attraction and power of deductive reasoning depends upon the premises being known as true. Unfortunately, the problems in the life sciences do not permit us the luxury of such “strong” deductive syllogisms. We must rely on a much weaker kind of syllogism:

If A is true, then B becomes more plausible.

And the inverse:

If B is false, then A becomes less plausible.

For example, if a culture test is negative (no bacteria detected), it becomes more plausible that the canal is “bacteria free,” but we are by no means certain of it. As we shall soon see, “plausible” can be a very long way from “probable,” depending upon a great many other factors.

The important fact to understand is that our form of reasoning in the life sciences is inductive, not deductive, and we are forced to use “weak” syllogisms, not “strong” ones. When you have only “weak” syllogisms, “doing the numbers” correctly as the above mammography/breast cancer example suggests is the only way to avoid cognitive errors or fall prey to what we call “cognitive illusions.”

So perhaps we are just as careless as the Root Cause producers have been with our inferences about disease causation and should be more circumspect and humble about what we think we know with certainty.

In Root Cause, a similar conditional probability statement is made, then a second occultly inverted, then inferred:

- The probability of having had a root canal given that a person has cancer is 98%.

- Therefore, the probability of having cancer given that one has had a root canal is 98%.

While these two statements sound similar, like the mammography example above, they are not. This is a wide and pervasive error in critical thinking. It manifests in understanding how screening tests such as PSA and mammography work, in research conclusions, and in a rife misunderstanding about what statistical significance means and how p-values work. The list is seemingly endless.

In endodontics, a longstanding error is starting with a lack of evidence of bacteria, which does not equal evidence of a lack of bacteria, let alone does it equal bacteria-free. These widespread and longstanding errors in critical thinking force us to explain around the observations and make claims that are not evidence-based. When speaking to patients on the topic, here is a simple example to illustrate the defective logic:

- The probability of having had Romaine lettuce given that a person has cancer is 100%.

- Therefore, Romaine lettuce causes cancer.

Another common cognitive fallacy here is to confuse correlation with causation (Figure 3). Similarly, as Greenland points out, lack of evidence of harm does not equal evidence of safety, nor does it equal safe. Because the language sounds so similar, common cognitive biases and lack of cognitive machinery and the ability to actually compute this inverse probability along with the seeming plausibility allow this to happen unchecked.

|

| Figure 3. Many factors in life have very similar correlations but no real causative association. “Correlation does not imply causality” is the rallying cry of all careful investigators because it is such a common cognitive illusion. This was first pointed out by eminent statistician Sir Ronald Fisher, who claimed smoking didn’t cause lung cancer—and eventually died of the disease. (credit Tyler Vigen) |

As a general principle, the safety of any medical or dental procedure actually cannot be demonstrated, and in many cases it is unethical to perform a trial designed to find harms. There is no randomized trial demonstrating that cigarette smoking is harmful and causes cancer, nor is there a clinical trial demonstrating safety. It would be unethical to randomize patients into such groups.

Similarly, there are no clinical trials demonstrating the safety of endodontic therapy. Sadly, there are no trials demonstrating its effectiveness over doing nothing or active surveillance. Thus the safety of endodontics cannot be demonstrated, only a lack of evidence or failure to find harm. Even if these kinds of trials were possibl

e, any results would only be meaningful when compared to the alternatives of extraction and any ensuing procedures, or leaving the tooth as it is.

“Despite demands for absolute safety assurance, such assurance is impossible according to modern philosophy of science and its statistical operationalizations. We never accept anything as true, only as un-refuted so far. That includes safety. This means when a patient asks: ‘Is this safe?’ the strongest scientific answer is: ‘So far, no one has shown it to be harmful,’” Greenland noted.

People want assurances of absolute safety, so our professional societies and associations will give those assurances to them. This is unscientific. While we would all like to present our patients with the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, we are fundamentally unable to discover it in this domain.

The scientific method is fundamentally unable to prove these kinds of hypotheses. We cannot prove that all swans are white with 100, 1,000, or even 1 million swans. Lack of evidence of non-white swans does not prove all swans are white. We can only increase our level of evidence for that hypothesis. In contrast, a single black swan can disprove the hypothesis that all swans are white. Thus the quest for proof of safety is impossible, just as the proof for safety efficacy is impossible.

At a minimum, then, we owe our patients an honest presentation of the evidence, all of the evidence, and our best interpretation of the evidence. This is central to the doctrine of informed consent. Any less is being less than honest in our dealings with our fellow man.

A Modern Understanding of Microbiology

If the poor choice of the mode of logic isn’t enough to convince you, in endodontics, we have been captive to the Kochian Germ Theory of Disease so completely that we think a simple quantification of bacterial load can give us estimates of the disease risk or disease pathogenicity—a theory that can now be seriously challenged.

An even more general and important point is that any attempted description of host-pathogen relationships based on microbiologist Robert Koch’s binary logic of “infected versus non-infected” or “pathogogenic versus non-pathogenic” or “diseased versus non-diseased” is unlikely to produce any clarity at all.

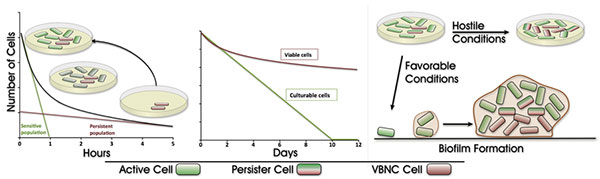

|

| Figure 4. Current thinking about microbial life is that biofilm formation and dormancy preclude bacteria detection by traditional means such as culturing. Bacteria exposed to a hostile environment form biofilms and may go through several processes to reduce their metabolic needs and enter a state of dormancy. This may allow them to survive, undetected for years or even decades. A precipitating event may change conditions and return the microbial community to a state where it may reproduce or induce host damage.15 Nelson & Thomas raised this as a possible reason for implant failure in seemingly healed sites. |

It is estimated that 99% of bacterial life on this planet hasn’t been cultured. And of this number, only a miniscule percentage is capable of causing disease, and then only in a susceptible host. When it comes to chronic disease of microbial origin, Koch’s postulates cannot be fulfilled because it is not possible to duplicate all the variables involved in disease expression on both sides of the host-pathogen equation.

“In addition, Koch’s postulates do not allow researchers to readily address naturally occurring environmental, nutritional, genetic, and other relevant factors that influence disease causation and do not consider the pathogenic complexities induced by sequential or simultaneous infection with more than one pathogenic microorganism,” said research biologist Michael Kosoy, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.8

In Root Cause and elsewhere, Dr. Joseph Mercola1,9 reports that evidence regarding the toxicity of root canals goes back to the work of Dr. Weston Price more than 100 years ago. Mercola reports that Price’s work “was revered by both the dental and medical professions” and that Price was considered “the world’s greatest dentist.”

Neither of these statements is widely regarded as true. The greatest dentist of that era is known to every single dental student and dentist as G. V. Black, widely heralded as one of the founders of modern dentistry and the father of operative dentistry.

Price’s work was certainly important and influential, coming shortly after Robert Koch is reported to have published his postulates of microbial infection in 1890. While Price’s work was wideranging and important, and much of it was well received by many in the dental and medical community, the theory of focal infection attributed to him remained under heavy criticism.

In fact, it was a year after Koch’s postulates that the pioneer in this domain, W. D. Miller, published his 1891 article “The Human Mouth as a Focus of Infection” in both The Lancet and Dental Cosmos.10-12 In this article, Miller lists 150 cases in which “severe complications resulted from diseased teeth or operations in the mouth.” These were all septic, sick patients. Many of these patients died.

It is worth noting that for many of the patients who died, the cause of death is listed as (attempted) extraction of the tooth. However, one of these patients had a root canal and survived. Miller continued to write a series of articles for Dental Cosmos over the ensuing years of which Price took note, publishing his book decades later in 1923 and his landmark article in JAMA in 1925.13,14

Based on this work, assertions are made that when endodontically treated teeth are removed, many of these systemic problems are cured. Arthritis goes away, multiple sclerosis disappears, and fatigue is gone. Mercola himself reports that decades of incurable acne went away after he had an untreated but endodontically involved tooth removed when he was 40.9 Perhaps his acne would have disappeared if he had the tooth endodontically treated instead of removed? Regardless, the inference is that removal of an endodontically involved or endodontically treated tooth removes the bacteria from the host. What if this isn’t true?

In a landmark study,15 Nelson & Thomas examined apparently healed extraction sites prior to implant placement where the offending tooth had been removed at least three months prior. Twenty percent of these sites had cultivable bacteria. Given a modern understanding of biofilms and the microbial lifecycle in which dormancy is the dominant state, this certainly represents a marked underestimation of the actual prevalence of bacteria in seemingly healed extraction sites (Figure 4).

“Bacteria can persist as a contaminant in apparently healed alveolar bone following extraction of teeth with apical or radicular pathosis. We have presented evidence that bone from previously infected and apparently healed sterile sites may harbor bacteria as a contamination, which may be reactivated to an infection during clinical implant therapy. We have surmised that the mechanism involved is because of the eradication of partly healed sclerosed bone harboring microbial biofilm,” Nelson & Thomas concluded.15

What this means, then, is that by the time there is actual evidence of an endodontic problem, the cat is likely out of the bag, and the periapical tissues may already harbor biofilm. Further still,

extraction of the offending tooth leaves an open wound in clear communication with the oral cavity. In those cases, fully two-thirds of the sites had cultivable bacteria. By and large after extraction or endodontic treatment, symptoms resolve, sinus tracts close over, and bone regenerates. So it would seem that we don’t need to get all the bacteria out for things to heal.

We may follow in this portion of the conversation with the example of bacteria on the skin or elsewhere in the body. Pointing to the back of the hand, we may ask our patient if there is bacteria there. Of course, the answer is yes. But then we would ask if that means there is an infection. And what is an infection, anyway? We may next point out that the presence of bacteria does not mean there is a problem or disease, or, more importantly, disease that matters.

The fundamental idea that all bacteria are bad and must be eliminated stems from the Kochian planktonic view of bacteria and disease as an either/or, present/absent dichotomization. It is important to understand that the Kochian Germ Theory of Disease addressed only a specific class of diseases: acute, infectious, pandemic or epidemic, planktonic diseases such as anthrax, cholera, and plague. As a disease model for non-planktonic, chronic, biofilm disease, the model fails us, as it did for Koch when he tried to apply it in trying to cure tuberculosis, a chronic biofilm disease.

Casadevall & Pirofski provided a more modern understanding in their seminal paper, “The Damage-Response Framework of Microbial Pathogensis.”16

“First, microbial pathogenesis is the outcome of an interaction between a host and a microorganism, and is attributable to neither the microorganism or host alone. Second, that the pathological outcome of the host-microorganism interaction is determined by the amount of damage to the host. Third, that damage to the host can result from microbial factors and/or the host response. The outcome of many host-microorganism interactions can be either beneficial or detrimental to the microorganism, to the host, or to both the microorganism and the host,” Casadevall & Pirofski wrote.

”There is no disease that you either have or don’t have—except perhaps sudden death or rabies. All other diseases you either have a little or a lot of,” noted epidemiologist Geoffrey Rose.17

Guidelines for Treating Patients

One approach the clinician might take with the apprehensive and concerned patient is to start the endodontic procedure carefully under the rubber dam, place an intracanal medicament like Ca(OH)2 or Vitapex, and see how the patient responds. The tooth already has been microbially colonized, often for months, and is unlikely to become more pathologically colonized with treatment.

If the clinician decides that the tooth is outside the scope of endodontic treatment available in-house, a referral to an endodontist with a microscope and CBCT is another option. The microscope allows the treating clinician to address the endodontic issues while preserving as much sound tooth structure as possible for the restorative dentist, and the CBCT can allow early assessment of radiographic clearing.

It is critical that the endodontist place the definitive coronal restoration upon completion of the radicular endodontics, whether it is a complex post-core buildup followed by an indirect restoration at the restorative dentist’s office or a simple access closure through a crown. The traditional management after obturation of placing a temporary restoration such as a cotton pellet and Cavit should be avoided at all costs, as this is not evidence-based and not in the best interest of the patient.

In the event that the tooth does not respond to treatment, or the patient ultimately decides against it, the tooth can always be removed if a role in a systemic problem is a concern or suspected. We may tell our patients that we can always start the root canal, clean the tooth out, put in some anti-microbial temporary filling material, and see how they feel. Removal of the tooth is always a option if we find out that it’s not working out. However, if we start out by just pulling the tooth, we reduce the number of options.

“People are raised with the idea that somehow things can be risk free and safe. That doesn’t really exist in medical choices. This problem of asserting safety would exist even if the clinical trials and data were perfect,” Greenland noted.4

All of this is dramatically easier if the clinician has ample followup radiographs of previously treated cases with clear radiographic findings and radiographic evidence of resolution of apical periodontitis. While unscientific, the power of a single case presentation of a similar problem on a patient seen within the previous week cannot be underestimated.

Talking Points for Patients

What works best for this environment that we have, including dealing with people like Mercola or Root Cause or alternative dental practitioners, is honesty. Assurances of safety such as the statements from the professional associations shown earlier are complicated by disputes and vast misunderstandings about what constitutes refutation and lead to the problems in logic and scientific inference identified above.4

Our best evidence is that endodontic treatment does not completely eliminate bacteria from an infected tooth, nor does endodontic treatment predictably cure apical periodontitis, in the very strict sense that no chronic disease is ever eliminated with certainty. This evidence dates back to seminal papers from more than 50 years ago, and it has largely been validated over the ensuing decades.

Modern CBCT has not helped this problem. Instead, people that were “healthy” with projection radiography seem to have migrated to “diseased” with CBCT.6 The idea of screening patients with CBCT to detect latent or occult “disease” as suggested by Bale-Doneen22 is fundamentally misguided. Like most screening programs on asymptomatic seemingly healthy patients, it is likely to lead to significant over-diagnosis, over-treatment, and harm.

So what is the practicing clinician to do? Patients don’t have our expertise and are not prone to think through all the options and the consequences of each choice as thoroughly as they should and are able to do. These problems can be mitigated somewhat by teaching that all choices involve risk/benefit tradeoffs.

(Here, we use the term risk in its common or lay meaning, in contrast with the technical use of the term risk, which is quantifiable. Many of these conversations should actually involve marked uncertainty, which denotes the lack of quantifiable or measureable knowledge about the relative probabilities of beneficial or harmful effects or outcomes. The interested reader is referred to Taleb and Knight.18,19)

Then we can say that we think they should get a root canal, since the benefits outweigh the risks, or that the risk we expect from failure to get a root canal is far larger than the risk we expect from getting one. Root Cause illuminates only half of the half of the terrain in which endodontically involved patients find themselves. Our job is to fully illuminate the terrain and the risks and benefits of all of the options.

We offer four talking points for clinicians to discuss with rightfully concerned patients.

First, own the primary premise in Root Cause straightaway. We do not eliminate micro-organisms and bacteria from the root canal system with endodontic treatment. Even if this procedural objective were accomplished, we are not able to completely seal the system, and it is likely to become re-colonized by bacteria in short order. This re-colonization is ensure

d if the patient is sent to an endodontist who places the traditional cotton/Cavit access closure.

Second, removal of the tooth does not ensure that bacteria will be eliminated from the bone. Tooth removal creates an open wound in the oral cavity replete with a wide range of microbial life. To think that the extraction socket is sterile and will remain sterile defies the best evidence and flies in the face of common sense. We largely heal regardless of the presence of bacteria.

Third, dental implants have their own sets of problems. It is becoming increasingly known that dental implants have a variety of failure modes, many of which appear to have a microbial etiology.

Finally, bridges also have their own problems, the most significant of which is the increased likelihood of a retainer developing recurrent decay, an endodontic problem, or worse, landing the patient right back in the same situation but with fewer teeth.

Closing Thoughts

Healthcare requires informed, honest, and transparent clinicians. We believe the most decisive reason for the lack of health literacy in patients is far more likely to be the widespread amount of misinformation or the misframing of data that makes it difficult to interpret. These sources include poorly designed, analyzed, and reviewed scientific articles, to say nothing of the risk of illiterate clinicians and journal editors. Also of concern is inaccurate and misleading patients’ brochures, as well as the popular press and associated media hype.5

With this issue, neither side is being honest, transparent, or accurate. Guidelines that are faithful to what is actually known and complete, accurate, and combined with transparent reporting in scientific journals are needed. The scientific community should demand that all journals reject any manuscript that does not deposit its raw data and make it publicly accessible. Most journal editors, peer reviewers, clinicians, and patients do not understand the available medical evidence.

Every medical and dental school should teach its students critical thinking skills, how to understand evidence in general and health statistics in particular, and how to better present that information to patients. As well, elementary and high schools should start teaching the mathematics of uncertainty—statistical thinking. While a critical mass of informed clinicians and patients won’t resolve all healthcare problems, it may be able to be a significant trigger for better care.

The authors wish to sincerely thank Professor Sander Greenland and Professor Arturo Casdevall for their review of this manuscript.

References

- Bailey F, director. Root Cause [documentary]. 2019.

- Taylor PE, Cole JM, Ryan ME. Letter on Root Cause to executives at Netflix, Amazon, Apple, and Vimeo, from the American Association of Endodontists, American Dental Association, and American Association for Dental Research, January 29, 2019.

- European Society of Endodontology. The benefits of root canal treatment response. Letter and position statement regarding Root Cause. 2019.

- Greenland S. An epidemiologist looks at our disease model from a critical perspective. Presented at: TDO User Meeting & Scientific Session; Fall 2015; San Diego, CA.

- Wegwarth O, Gigerenzer G. The barrier to informed choice in cancer screening: statistical illiteracy in physicians and patients. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2018;210:207-221.

- Khademi JA. Advanced CBCT for Endodontics: Technical Considerations, Perception, and Decision-Making. Hanover Park, IL: Quintessence Publishing; 2017.

- Ross WD, Smith JA. The Works of Aristotle. Charleston, SC: Nabu Press; 2010.

- Kosoy M. Deepening the conception of functional information in the description of zoonotic infectious diseases.Entropy. 2013;15:1929-1962.

- Mercola J. Mercola Discusses Root Canals . October 10, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oYbOvx54OOs. Accessed April 30, 2019.

- Miller WD. The human mouth as a focus of infection. Dental Cosmos. 1891;33(9):689-713.

- Miller WD. The human mouth as a focus of infection. Dental Cosmos. 1891;33(10):689.

- Miller WD. The human mouth as a focus of infection. Lancet. 1891;138:340-342.

- Price WA. Dental Infections and the Degenerative Diseases. Cleveland, OH: Penton Publishing; 1923.

- Price WA. Dental infections and related degenerative diseases. Some structural and biochemical factors. 1925;84:254.

- Nelson S, Thomas G. Bacterial persistence in dentoalveolar bone following extraction: amicrobiological study and implications for dental implant treatment. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2010;12:306-314.

- Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. The damage-response framework of microbial pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2003;1:17-24.

- Rose G. The Strategy of Preventive Medicine. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1992.

- Taleb NN. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Random House; 2010.

- Knight FRisk, Uncertainty, and Profit. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 1921.

- Ayrapetyan M, Williams TC, Oliver JD. Bridging the gap between viable but non-culturable and antibiotic persistent bacteria.Trends Microbiol. 2015;23:7-13.

- Internet Movie Talking Points [AAE 2019]

- BaleDoneen Method Statement in Response to “Root Cause” Documentary | BaleDoneen Method [Bale & Doneen 2019]

Dr. Khademi received his DDS from the University of California San Francisco and his certificate in endodontics an

d did his MS on digital imaging at the University of Iowa. He is in full-time private practice in Durango, Colo, and was an associate clinical professor in the department of maxillofacial imaging at University of Southern California and is an adjunct assistant professor at St. Louis University. He can be reached at jakhademi@gmail.com.

Disclosure: Dr. Khademi discloses a financial interest in SS White and Carestream Dental.

Dr. Carr lives and maintains a full-time practice limited to endodontics in San Diego. He also is the founder and president of TDO Software. He received his DDS from the State Univesity of New York at Buffalo and served as a line officer and dental officer in the US Navy before earning his Endodontic Certificate at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He is a Diplomat with the American Board of Endodontics and the founder and director of the Pacific Endodontic Research Foundation as well. And, he is the inventor of the ultrasonic root-end preparation technique.

Related Articles

“Root Cause” on Netflix: Can Root Canals Make You Sick?