|

|

Genomic record matches fossil record in the whales’ common ancestor, say UC Riverside biologists |

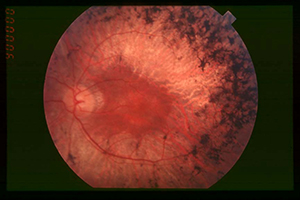

RIVERSIDE, Calif.—In contrast to a toothed whale, which retains teeth that aid in capturing prey, a living baleen whale (blue whale, fin whale, humpback, bowhead) has lost its teeth and must sift zooplankton and small fish from ocean waters with baleen or whalebone, a sieve-like structure in the upper jaw that filters food from large mouthfuls of seawater.

Based on previous anatomical and fossil data studies, scientists have widely believed that both the origin of baleen and the loss of teeth occurred in the common ancestor of baleen whales about 25 million years ago. Genetic evidence for these, however, was lacking.

Now biologists at the University of California, Riverside provide the first genetic evidence for the loss of mineralized teeth in the common ancestor of baleen whales. This genomic record, they argue, is fully compatible with the available fossil record showing that the origin of baleen and the loss of teeth both occurred in the common ancestor of modern baleen whales.

“We show that the genetic toolkit for enamel production was inactivated in the common ancestor of baleen whales,” said Mark Springer, a professor of biology, who led the research. “The loss of teeth in baleen whales marks an important transition in the evolutionary history of mammals, with the origin of baleen laying the foundation for the evolution of the largest animals on Earth.”

Previous studies have shown that the dental genes enamelin, ameloblastin and amelogenin are riddled with mutations that disable normal formation of enamel, but these debilitating genetic lesions postdate the loss of teeth documented by early baleen whale fossils in the rock record.

Springer’s team focused on the evolution of the enamelysin gene, which is critical for enamel production in cetaceans and other mammals. Cetacea includes toothed whales (e.g., sperm whales, porpoises, dolphins) and baleen whales.

They found that the enamelysin gene was inactivated in the common ancestor of living baleen whales by the insertion of a “transposable genetic element”—a mobile piece of DNA.

“Our results demonstrate that a transposable genetic element was inserted into the protein-coding region of the enamelysin gene in the common ancestor of baleen whales,” Springer said. “The insertion of this transposable element disrupted the genetic blueprint that provides instructions for making the enamelysin protein. This means we now have two different records, the fossil record and the genomic record, that provide congruent support for the loss of mineralized teeth in the common ancestor of baleen whales.”

The study, which appeared online last week (Sept. 22) in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, included eight baleen whale species and representatives of all major living lineages of Cetacea. The researchers examined protein-coding regions of the enamelysin gene for molecular cavities that are shared by all baleen whales.

Next, the researchers plan to piece together the complete evolutionary history of a variety of different tooth genes in baleen whales to provide an integrated record of the macroevolutionary transition from ancestral baleen whales that captured individual prey items with their teeth to present-day behemoths that entrap entire schools of minute prey with their toothless jaws.

Springer was joined in the study by UC Riverside’s Robert W. Meredith, a postdoctoral associate and the first author of the paper; John Gatesy, a professor of biology; and Joyce Cheng, an undergraduate researcher.

The National Science Foundation supported the study through grants to Springer and Gatesy.

|