By studying a rare disease known as APECED, researchers at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) said they have uncovered an unexpected immune mechanism that promotes susceptibility to fungal infections of mucous membranes in the mouth and elsewhere. The findings suggest potential therapies for people with APECED and pave the way for work to investigate these tissue-specific immune responses in other diseases, they said.

“Because the mouth is easy to access and biologically similar to mucosal tissues throughout the body, it’s an obvious site to study mechanisms of disease,” said Niki Moutsopoulos, DDS, PhD, senior author and an immunologist with the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. “Studying how rare immune diseases affect the mouth can reveal general insights about the immune system and lead to better interventions for both rare and common diseases of the mouth and elsewhere in the body.”

APECED, or autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy, is a genetic disease that leads to defects in the autoimmune regulator (AIRE) protein, which helps teach immune cells how to distinguish the body’s own cells and tissues from foreign invaders. It can lead to diverse symptoms including chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC), infections with the yeast fungus Candida that are limited to the mucous membranes and nails and do not spread throughout the body.

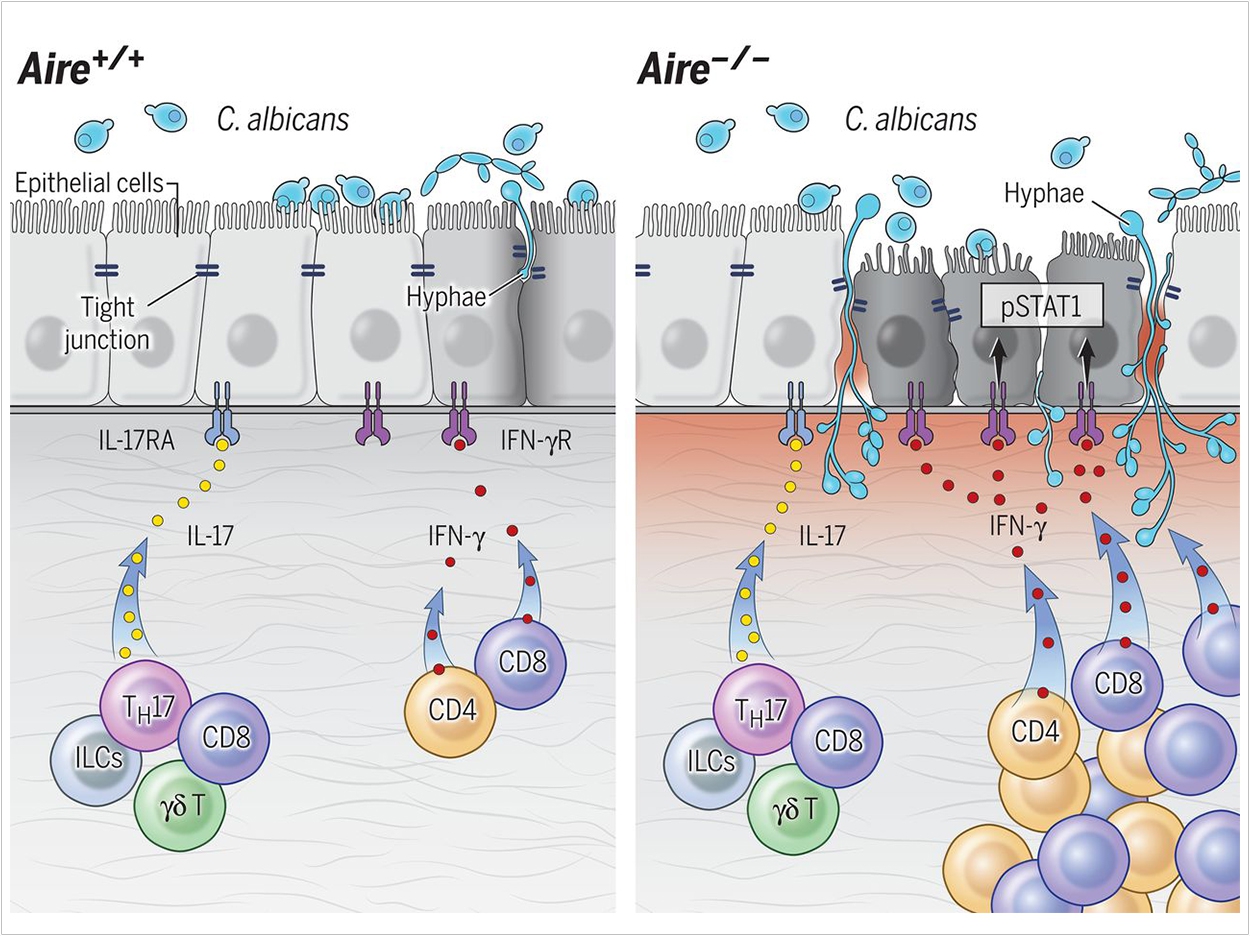

Previously, scientists had established that defects in a type of protective immune response known as “type 17” immunity can enhance vulnerability to CMC. But the researchers found that type 17 responses at mucosal tissues were intact both in people with APECED and in a mouse model of the disease, suggesting that a different mechanism promotes CMC susceptibility.

By studying mice engineering to lack AIRE, the researchers found that abnormal T-cell responses promote inflammation in mucosal tissues and disrupt the protective outermost layer of cells, facilitating Candida infections. T cells typically play a key role in protecting healthy mucosal tissues from fungal infections, but in AIRE deficiency, they exhibit enhanced “type 1” T-cell responses that instead promote infection.

The researchers also observed this aberrant type 1 T-cell immunity in samples from the oral mucosa of a large cohort of APECED patients enrolled in a natural history study at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center. T-cells produce excessive amounts of a key cell-signaling protein called IFN-gamma, which activates a cell-signaling process involving molecules called JAKs and STAT1, leading to damage to the barrier of cells at the surface of mucosal tissues.

Administering an antibody that blocks IFN-gamma or the drug ruxolitinib, which impedes JAK/STAT1-signaling, improved mucosal fungal infections in mice lacking AIRE. This suggests that ruxolitinib or the anti-IFN-gamma antibody emapalumab, which are both approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for other diseases, potentially could be effective for prevention or treatment of CMC in people with APECED.

The findings enhance scientific understanding of how fungal infections take hold and also will inform efforts to better understand whether type 1 immune responses contribute to CMC in other diseases, such as Down syndrome or STAT1 gain-of-function mutations, the researchers said.

The study, “Aberrant Type 1 Immunity Drives Susceptibility to Mucosal Fungal Infections,” was published by Science.

Related Articles

Microorganism Signals Combat Candida Albicans Infections

When Candida Albicans Resists Medication, Starve It Instead

Researchers Identify Mechanics Behind Oral Thrush Infections