Introduction

Clinical facts are often obsoleted by progress. When I began designing variably tapered shaping files in 1991,1 my objective was to create a 20-.06 hand file (0.2-mm tip D with a .06 taper) that could cut to length without help from any other shaping instruments. This followed an epiphany I had that cutting tapered shapes in root canals was needlessly difficult because we only had .02 tapered K-files at the time. As soon as I imagined this variably tapered file in my head and understood its potential, I wondered why nobody else had tried making files with tapers greater than .02 mm/mm. Shortly into the project’s development, that mystery was explained; the .06 tapered stainless steel prototypes were as stiff as a board, and every one of them came apart before half the RC prep was cut. Fortunately, NiTi metallurgy serendipitously came to endodontics in 1992 after it brought disruptive change (the good kind) to ortho. This exotic new alloy was 5 times more resistant to torsional stresses than stainless steel and was hyperflexible. Using this new metal, the next prototypes worked perfectly, cutting the entire shape in curved plastic research blocks with a single instrument, and GT (Greater Taper) Hand Files were born (Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. A 20-.06 GT Hand File (DENTSPLY Tulsa Dental Specialties) (circa 1992). The first single-file shaping instrument, it was used in a reverse balanced force cutting motion. |

Ironically, I totally missed the boat when NiTi rotary files were first introduced into the specialty shortly thereafter. At that time, the only dentists who used root canal files in handpieces were those using the expedient (but largely disrespected) Sargenti Technique. The Sargenti disciples used stainless steel files that had such frequent breakage problems that they inspired a remarkable workaround; they would instrument canals with Sargenti Sealer in the canal so that when a file came apart, it was just considered to be premature obturation. This association fed my distrust of handpiece-driven shaping.

When asked if I wanted GT Files in rotary form, I thought it sounded like a bad idea until I heard a young dentist at a trade show tell me, “I don’t use endo files unless they work in a handpiece.” That set me back on my heels and forced me to take another look at rotary instrumentation. Fortunately, my fear of missing out overcame my self-imposed dogma, and GT Rotary Files became the flagship product of DENTSPLY Tulsa Dental Specialties (now Dentsply Sirona Endodontics). This disruptive technology was a win for everyone involved. The companies sold files for $10 instead of $1.50, clinicians nearly doubled their productivity, and patients got shorter treatment times and more predictable outcomes. It was truly a golden age in endodontics, but most educators relegated rotary instrumentation to shaping procedures, believing that hand files were necessary to traverse canals to establish glide paths before bringing handpiece-driven files into the field.

|

| Figure 2. Comparison of chip space in the cross-sectional geometry of square and triangular files. The triangular file is of the same tip size but with 57% more chip space, radically improving its ability to cut to length without apical blockage. |

Fast forward to 2015: A new rotary file line has been introduced, and I get my first opportunity to check it out. When testing new rotary files—mine or anybody else’s—I begin by intentionally breaking them in extracted teeth to find the limit, then work my way backward into indications for safe use. The easiest way to break any rotary file is to shove it repeatedly into small, dry, curved, previously un-negotiated molar canals, so I began my study of these new instruments by misusing a small size 15-.06 rotary file that way. Oddly, rather than breaking it, I cut to length! I thought it must have been a fortunate accident because I “knew” that rotary files should never be cut to length before the Glidepath has been established with hand files, and I knew that I would block small molar canals if the first instrument I cut to length had a #15 tip diameter.

|

| Figure 3. A 13-.06 Traverse Rotary Negotiation File (Kerr Endodontics) with a 1.0-mm maximum flute diameter limitation. Note the variable-pitch flute angles, open at the shank end and progressively tighter toward the tip. The strength and flexibility this design offers is critical when using rotary files with tip diameters smaller than 0.25 mm—especially during rotary negotiation procedures. |

Regardless, these 15-.06 files proceeded to cut to length in 19 of 20 dry, curved mesial canals in extracted lower molars, presenting me with the unusual challenge of having to deconstruct an unexpected success rather than the usual need—during development work—to deconstruct failures. Fortunately, my earlier experience of not “getting” handpiece-driven NiTi files helped me to accept a possibility beyond the realm of my imagination, that rotary files can be used as the first file to length during negotiation procedures.

Fortunate Accidents as Invention

The list of reasons why these rotary files shouldn’t be able to cut to length as the first file included a lack of tactile feel with a handpiece, the likelihood of file breakage, a risk of blockage, and a risk of ledging impediments. Of these, the apical blockage issues—or the lack thereof—with these rotary negotiating files were the most mysterious. One of the most common RCT experiences neophyte dentists have is unexpected and irreversible apical blockage, and this happens while doing everything exactly as taught: irrigating with NaOCl, working a #08 and #10 K-File to length (irrigating between files), and then irrigating again and taking the #15 to length. It’s a simple technique to describe but, far too often, the #15 hangs up short of length and, when smaller files are taken in, it’s discovered that there is an impenetrable apical blockage.

|

|

| Figure 4a. An unbent #10 K-File meets loose resistance to apical file placement—identifying an impediment. Figure 4b. A #10 stainless steel K-File is smoothly bent 90° to the last flute with an Endo-Bender plier (Kerr Endodonti cs). Figure 4c. A pre-bent #10 K-File is finessed around the impediment. Figure 4d. A #10 K-File is worked to length and beyond with watch-winding/push-pull motions. Figure 4e. A #15 K-File is worked to length and beyond with watch-winding/push-pull motions. Figure 4f. An unbent #10 K-File is then used to confirm the presence of an impediment and measure the length to it. |

Figure 5. An Endo-Bender plier imparting a bend to NiTi file by overbending it. |

|

|

| Figure 6a. An unbent K-file meeting an apical impediment. When an impediment is encountered, the stop on the file is shortened to the coronal reference point, revealing the distance from the reference point to the impediment. Figure 6b. A 30-.06 rotary file, cutting shape 1-mm short of the impediment length. Figure 6c. A pre-bent 13-.06 Traverse File (see Figure 5). Figure 6d. A pre-bent tip of a Traverse File maneuvered past the impediment. Figure 6e. A handpiece is attached to the latch grip handle of Traverse File, and the file is taken to length and beyond only once. |

Figure 7. Obturating beyond impediments with conefit. |

|

| Figure 8. Obturating beyond impediments with carriers. |

The predominant theory explaining these untoward outcomes was that the 50% increase in tip diameter between the #10 and #15 K-Files was too great and that we needed a #12.5 size to alleviate this challenge. In fact, the real reason for this blockage was that the #15 K-File—the first instrument approximating the apical diameter of small canals—acts like a piston, compacting pulp remnants into the apical constricture. Proof of this theory is that irreversible blockage rarely occurs in a necrotic case. So, how does it work out that a #15 K-File is a deadly blockage former, but a rotary file, with the same tip diameter, cuts to length as the first file in vital cases without ever causing compaction of apical debris?

The answer is found in the differences in cross-sectional geometry between the 2 files with the same tip diameters—the K-File is square and the rotary file is triangular, with 57% greater chip space than the square file (Figure 2). When a square #15 K-File meets a pulp stump at the end of a canal, it doesn’t have enough chip space to allow the pulp to be penetrated, so the organic debris gets pushed ahead of the file tip, compacting it into a solid mass of impenetrable collagen. Triangular rotary files behave very differently, as they can cut through the pulp because there is adequate room between the helical flutes for the pulp tissue to be held until the file is removed and debrided.

The remaining procedural concerns with rotary negotiation instruments revolve around their inability to advance when meeting impediments in the primary canal path, as well as the potential for ledging in that situation, and the worry that the tactile feedback from handpiece-driven files will be inadequate to the mission of sneaking through tortuous canal pathways compared to the tactile clues we depend on during hand file negotiation.

Requirements for rotary files that can safely be used for handpiece-driven negotiation are fairly stringent. The files must be heat treated to reduce the accumulation of cyclic fatigue—this procedural advance wouldn’t be possible without it—and the flutes must have flute angles that vary along the length of the files. Specifically, they must have tighter flute angles in the tip portions of the files. This adds strength due to the additional metal delivered by the additional flutes, and, at the same time, more frequent flute pitches also increase the file tip’s flexibility. Ideally, the same file has more open flute angles as it progresses from tip to shank to maximize cutting efficiency and debris removal (Figure 3). Designed specifically for rotary negotiation (currently an off-label use), new Traverse Files (Kerr Endodontics), in sizes 13-.06 and 17-.06, have these features. In addition, they are designed with a maximum flute diameter (MFD) limitation of 1.0 mm to prevent coronal over-enlargement.

|

|

| Figure 9. The distal root in a mandibular molar with trifid division of the primary canal. The trifurcation was 4.0 to 5.0 mm from the dogleg root apex, frustrating all efforts to fit a cone to length in any of the 3 apical portals of exit and potentially leaving 10.0 to 15.0 mm of unfilled canal space. The best obturation solution was carrier-based, as carriers are capable of moving warm gutta-percha and sealer more than 1 mm beyond the final position of the carrier. Due to the great length of canals beyond the impediment, I left more sealer in the canal than usual, and, instead of carefully placing the GTX Obturator to length in 3 to 4 seconds, I slammed it home in a single second so more sealer and GP would be propelled ahead of the carrier rather than giving it enough time to escape coronally around the carrier as is typically done. The postobturation radiograph shows all 3 branches of the distal canal filled. | Figure 10. J. Morita’s cordless handpiece is the first cordless endodontic handpiece with an onboard apex locator, making this an ideal driver for Traverse Files when used for rotary negotiation. |

|

| Figure 11. This mandibular molar with multiplanar curvatures was negotiated with rotary files, achieving length in all canals within 5 minutes without the use of any hand files. |

When using rotary negotiating files, an attitude of acceptance is helpful as the clinician never knows if he or she is in a canal that will allow the instrument to only perform as an orifice opener (typical with MB2 canals), if it will only cut to the apical third before resisting further advance, or whether it will cut all the way to length. Regardless of the final depth achieved with rotary negotiating files, it is critical that they be frequently removed to clean the cut dentin debris out of the flute spaces and to examine the flutes for damage. When the chip spaces between flutes are filled with cut debris, further apical progress will shove this debris laterally, plugging lateral anatomy, or worse, the file can come apart as torsional stresses skyrocket when files are forced into this sea of sludge while rotating.

Be aware that these files in th

is application are being asked to do the majority of the instrumentation in small canals—perhaps the only instrumentation in many—so they should be replaced early and often in multi-canalar teeth. Nearly all 4-canal molars treated in my office require 2 to 3 of these fragile yet aggressive instruments to cut to length in their small canals.

Managing Impediments Without Ledging

The final concern about the damage potential of these rotary file tips is when they encounter natural or unnatural impediments. As with all impediments, the first objective is to avoid engaging any of these natural irregularities, making them bigger. On the file design side, it is imperative that the file tips used for rotary negotiation be tumbled to a micro-radius during manufacturing, so it takes repeated attacks to ledge canal walls with them. You certainly do not want to ledge an impediment inadvertently because the file you are using has an aggressive tip geometry or a ragged finish.

On the procedural side, damage is best avoided by keeping a very light touch on the handpiece and by immediately removing rotary negotiating files the second they balk at cutting further apically. Immediately after rotary negotiating files balk in canals, they are removed; examined; cleaned; and, if the chip spaces were filled with cut dentin debris, they are returned to the canal with the expectation that they will cut deeper. Any time any rotary file balks again at the same depth when replaced into the canal, it is done. In this case, put the handpiece down, bend the very last 2.0 mm of an #08 SS White Burs K-File, orient the rubber stop to indicate the direction of the file bend, and hunt for a path around the impediment. When the pre-bent SS White Burs K-file has found a passive path around the impediment, the position of the indicator (indicating the direction of the file bend) on the rubber stop is noted so the pre-bent instruments to follow can be automatically moved through this path without searching for it every time (Figure 4).

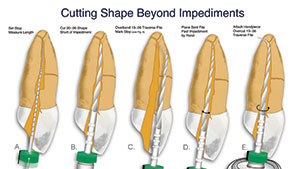

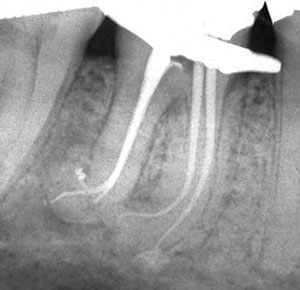

Once canals have been negotiated beyond the impediment and to length by hand with pre-bent SS K-files, the next challenge is to cut a final shape to length. I have tried several methods, including serial step-back shaping past the impediment with bent SS K-files, but the most elegant routine I’ve used to deal with this requires over-bending NiTi files (Figure 5), and it goes as follows:

Enlarge the canal short of the impediment. If the canal fails the #10 File Test, adjust the stop to the reference point and measure the distance from the reference point to the impediment. Cut the 17-.06 Traverse Rotary File a millimeter short of the impediment length and cut shape in the coronal two-thirds of the canal. In the case of a canal that is frustrating efforts to negotiate around the impediment, this additional coronal space will allow the tips of pre-bent files to arrive at the impediment still bent enough to sneak around tortuous canal paths (Figures 6a and 6b).

Thread a bent rotary file past the impediment and cut to length. After coronal shaping with a rotary file and apical negotiation to length with a bent #15 hand file, a 13-.06 Traverse Rotary Negotiating File is prepared by setting the stop to impediment length, overbending it with pliers until it retains a 30° to 40° curve, and using an indelible marker to mark the stop to indicate the position of the file bend so it can be threaded by hand around the impediment exactly as the bent SS files were (Figure 6c).

Once the tip of the 13-.06 file sneaks past the impediment (this is known when the file advances deeper than the impediment length and feels tight in the canal), the endo handpiece chuck is dropped onto the latch grip handle of the rotary file, the handpiece is activated, and the 13-.06 file is cut to length (and often beyond) in one fell swoop (Figures 6d and 6e). Done exactly this way—once to length and out—no significant transportation will occur.

About half the time, the final shape beyond the impediment will end up smooth enough to fit a GP cone around it (Figure 7). In canals with impediments that resist cone fitting after shaping is completed, carrier-based obturation is my filling method of choice (Figure 8). Carriers are an ideal solution to impediment cases that defy cone-fitting as they are much more capable of moving gutta-percha and sealer beyond the final position of the carrier than conefit methods (Figure 9).

CLOSING COMMENTS

The productivity gains rotary files brought to our shaping procedures are now being delivered to our negotiation procedures by advances in heat treatment and improvements in file design. In medium and large canals, this is a minor improvement, but in small molar canals, it is huge. Hand negotiating small molar root canals is physically taxing, so even when rotary negotiating files resist cutting to length, any hand instrumentation that follows will be eased by the early coronal enlargement they provide. Using Traverse Files to do rotary negotiation in J. Morita’s new cordless endo handpiece with an onboard apex locator (Figure 10) is genius. Using this elegant combination, the extremely complex lower molar in Figure 11 allowed rotary negotiation of all its tortuous canals within 5 minutes, complete with apex locator length capture and a .06 initial shape.

Molar root canal therapy has just gotten more efficient.

References

- Buchanan LS. Cleaning and shaping the root canal system. In: Cohen S, Burns RC, eds. Pathways of the Pulp. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Year Book; 1991.

Dr. Buchanan lives in Santa Barbara, Calif, where he maintains a practice limited to endodontics and implants in the same courtyard as his hands-on training facility, Dental Education Laboratories. He has taught thousands of dentists how to perform state-of-the-art root canal therapy, most often with tools he has invented. He invented 3-D printed tooth and jaw replicas to accelerate hands-on procedural training, profoundly changing dental CE experiences. Dr. Buchanan can be reached at the websites endobuchanan.com, delabs.com, and delendo.com.

Disclosure: Dr. Buchanan receives royalties on Traverse Rotary Files from Kerr Endodontics.

Related Articles

A Revolutionary Protocol for Endodontic Access

Continuous Wave Warm Gutta-Percha Obturation: Using Bio-Ceramic Sealers

The Continuous Wave of Obturation Technique, Part 1: Concepts and Tools