The number of patients—and, particularly, children—who have been injured or killed by dental sedation indicates that there are gaps in the standard of medical care being used during these procedures. Here are just some of the cases that we know about:

- 6-year-old Caleb Sears stopped breathing after receiving several different kinds of intravenous anesthetics during a tooth extraction.

- 5-year-old Amber Athwal suffered brain damage after receiving general anesthesia to extract some of her teeth.

- 17-year-old Sydney Gallegher died nearly a week after she suffered cardiac arrest after having her wisdom teeth pulled.

An investigation by the local ABC affiliate in Austin, Texas, identified at least 85 patients in Texas who died shortly following dental procedures from 2010 to 2015.

We offer seven keys to preventing more patients—especially children—from dying from dental sedation.

The Dentist Should Not Be the Anesthesia Provider and Monitor

In many of the fatalities following sedation for dental procedures, the same person was performing the dental procedure and monitoring the patient. As the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) “Guideline for Monitoring and Management of Pediatric Patients During and After Sedation for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures” states:

“The use of moderate sedation shall include the provision of a person, in addition to the practitioner, whose responsibility is to monitor appropriate physiologic parameters and to assist in any supportive or resuscitation measures, if required.”

Clinicians Should Be Trained to Recognize Respiratory Compromise and Be Able to Intervene Appropriately

The AAPD guideline, which applies not just to dental procedures but to sedation for all procedures, notes that children under the age of 6 years (and especially those under the age of 6 months) are particularly likely to suffer adverse events during sedation. It emphasizes that there is a very narrow margin in children between the intended level of sedation and much deeper sedation or anesthesia.

Therefore, the practitioner must be trained in moderate sedation and have the skills to rescue patients from such deeper levels. This would include the skills needed to:

- Rescue a child with apnea, laryngospasm, and/or airway obstruction

- Open the airway

- Suction secretions

- Provide continuous positive airway pressure

- Perform successful bag-valve-mask ventilation

- Insert an oral airway, a nasopharyngeal airway, or a laryngeal mask airway (LMA)

- Perform tracheal intubation

The guideline notes that these skills are likely best maintained with frequent simulation and team training for the management of rare events. Without appropriate and trained personnel attending to the sedated dental patient—and, particularly, children, as noted in the AAPD guideline—the safety of the patient is at risk.

Patients Should Be Monitored for Adequacy of Ventilation with Capnography

The updated AAPD guideline emphasizes the role of capnography in appropriate physiologic monitoring:

“A competent individual shall observe the patient continuously. Monitoring shall include all parameters described for moderate sedation. Vital signs, including heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and expired carbon dioxide, must be documented at least every 5 minutes in a time-based record. Capnography should be used for almost all deeply sedated children because of the increased risk of airway/ventilation compromise. Capnography may not be feasible if the patient is agitated or uncooperative during the initial phases of sedation or during certain procedures, such as bronchoscopy or repair of facial lacerations, and this circumstance should be documented. For uncooperative children, the capnography monitor may be placed once the child becomes sedated. Note that if supplemental oxygen is administered, the capnograph may underestimate the true expired carbon dioxide value; of more importance than the numeric reading of exhaled carbon dioxide is the assurance of continuous respiratory gas exchange (ie, continuous waveform). Capnography is particularly useful for patients who are difficult to observe (eg, during MRI or in a darkened room).”

Do Not Delay in Calling 911

In analyzing 78 cases of mishandled sedation or anesthesia, the Blue Ribbon Panel on Dental Sedation/Anesthesia of the Texas State Board of Dental Examiners found that, of the factors contributing to dental sedation incidents, the most common was that “the provider was slow to activate EMS [emergency medical services].”

Sure, the practitioner may be embarrassed over having allowed an adverse event to occur. However, any embarrassment is preferable to the death of the patient. We cannot stress this point enough. Do not delay in calling 911.

Practice, Practice, Practice

We must emphasize that every person in the dental practice, including clerical and front office staff, has a responsibility in an emergency. The only way to prepare all for such emergencies is to practice or perform drills. Since many dental practices employ part-time employees, that means drills must be performed on multiple occasions so all employees are familiar with their roles in emergencies.

In discussing factors that might have helped avoid the death of Joan Rivers, Kenneth P. Rothfield, MD, MBA, chairman of the Department of Anesthesiology at Saint Agnes Hospital in Baltimore and a member of the board of advisors of the Physician-Patient Alliance for Health and Safety, probably said it best when he told the Washington Post, “Unless you have drilled for it, and trained for it, it can be hard to pull off.”

Be Prepared

Be Prepared

Being prepared is a key to managing adverse events and taking steps to avoid patient deaths. We recommend two related tools to be prepared: pre-procedure huddles (briefings) and post-procedure debriefings. These meetings offer the opportunity to both plan for contingencies ahead of time and to analyze things that might have been done better after a procedure.

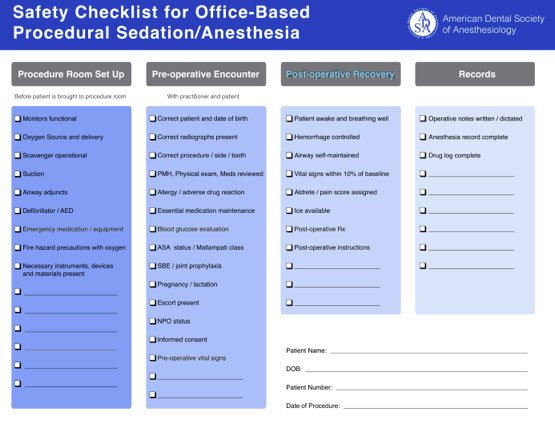

We also encourage the use of checklists as a reminder of the key steps to be followed. The American Dental Society of Anesthesiology provides a Safety Checklist for Office-Based Procedural Sedation/Anesthesia (see the figure). This checklist has broken down key considerations along the continuum of care: procedure room setup, pre-operative encounter, post-operative recovery, and records.

Restraints Should Only Be Used With Extreme Caution

Dentists sometimes use a papoose board when treating pediatric patients. Papoose boards restrain the patient from interfering with the dental procedure and may have contributed to the adverse outcomes in several cases. The AAPD guideline provides the following cautions to using papoose boards or other restraining devices:

“Immobilization devices, such as papoose boards, must be applied in such a way as to avoid airway obstruction or chest restriction. The child’s head position and respiratory excursions should be checked frequently to ensure airway patency. If an immobilization device is used, a hand or foot should be kept exposed, and the child should never be left unattended. If sedating medications are administered in conjunction with an immobilization device, monitoring must be used at a level consistent with the level of sedation achieved.”

Conclusion

Although we cannot say for certain whether these seven keys would have saved the lives of Caleb, Amber, and Sydney, we do know that the application of a higher standard of care, in accordance with AAPD recommendations, might indeed save the life of another patient.

Dr. Truax of the Truax Group is board-certified in neurology and internal medicine. A clinician and educator with more than 20 years of experience in medical administration, he has been involved in patient safety for more than 25 years. He was trained at Johns Hopkins Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital. And, he was a clinical association professor of neurology at the SUNY Buffalo School of Medicine. He can be reached at btruax@patientsafetysolutions.com.

Mr. Wong is the founder and executive director of the Physician-Patient Alliance for Health & Safety. A graduate of Johns Hopkins University and a former practicing attorney, he is a recognized healthcare and patient safety expert. Also, he is a founding member of the American Board of Patient Safety and a member of the editorial board of the Journal for Patient Compliance. He can be reached at mwong@ppahs.org.

Related Articles

Pediatric Sedation Safety Guidelines Get Updated

Dental Offices Need Emergency Preparedness Standards

Try Communication, Not Sedation, in Pediatric Dentistry