INTRODUCTION

Patients often present with bone quality or quantity that is not conducive to support a proper dental implant. Thus, a secondary surgical procedure is used to augment the bone so that the implant can be ideally positioned and stabilized. Dental implants have become a well-accepted mode of treatment to our patients. They present with missing teeth and request permanent replacement with fixed prostheses. The success of our modern dental implants is reliant on their ability to integrate into the bone. This requires a relatively healthy patient with no uncontrolled healing properties and adequate hard-tissue availability. Initial stability is paramount. Bone grafting procedures are well established in the profession. They involve adding a bone substitute into a deficient site to create volume and density. A common material used today is referred to as an allograft, which is graft material harvested and processed from another human.

Sinus tenting procedures can seem daunting to the general practitioner. As teeth are lost, we see physiologic shrinkage both palatally and vertically. The subsequent socket can lose 40% to 60% of bone structure in the first 3 years following extraction.1 The maxillary posterior region is further complicated by the fact that when teeth in the sinus area are removed, the sinus floor will fall, enlarging the sinus cavity. There is often not enough vertical height of hard tissue to predictably place a dental implant to help restore the site with an implant-retained crown. Sinus tenting, in some situations, can be a simple surgical procedure that lifts the maxillary sinus membrane upward to make some room for additional bone. This sinus augmentation provides increased availability of hard tissue to accept a dental implant. The maxillary sinus can be divided into compartments separated by septae.2 This must be evaluated thoroughly prior to any surgical intervention. It has been demonstrated in the literature that the newly formed bone around a grafted dental implant resembles native bone over time.3

|

| Figure 1. CBCT analysis of the sagittal view demonstrates inadequate bone height to accept a dental implant without impinging into the maxillary sinus cavity. |

CASE REPORT

Diagnosis and Treatment Planning

A 69-year-old female presented with several dental needs but wished to have a permanent tooth replacement in the maxillary first molar area to improve her broad smile. There were no contraindications found in her overall health that would have prohibited a dental implant restoration. However, CBCT analysis (Vatech America), which shows the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes, clearly demonstrated an inadequate height of hard tissue for ideal positioning and stability of a dental implant. The axial view shows the plane parallel to the ground, dividing the face from top to bottom. The sagittal view, which is most helpful for this clinical discussion, is the plane perpendicular to the ground, thus dividing the face from right to left. The coronal lane is the plane perpendicular to the ground, dividing the face from front to back.4 This 3-D evaluation helped to determine the possibility for bone growth in the sinus cavity and acceptable implant placement to support a fixed, implant-retained crown.

|

Clinical Protocol

Various techniques are used to elevate or fill the sinus cavity, and the procedure will depend on the available bone and how invasive the surgery really needs to be. In the more invasive Caldwell Luc procedure, the practitioner creates a lateral window in the area of the edentulous space, and the sinus is filled with the grafting material.5 In the less invasive sinus tenting procedure documented here, the maxillary sinus’s Schneiderian membrane is actually stretched during the elevation using osteotomes (instruments that are the shape of the implant body itself), but rather than excising valuable hard tissue, is used to compress the medullary bone, lift the sinus floor, and create the appropriate osteotomy to accept a stable dental implant. The Schneiderian membrane is actually bilaminar in shape with ciliated columnar epithelial cells on the internal portion and periosteum on the bony side.6 A significant tearing of this membrane could result in sinus congestion and could potentially affect osseointegration of the subsequent implant body.6 Small perforations can be repaired with a resorbable membrane placed by the surgeon, but larger holes should be prevented.

Figure 1 shows the CBCT analysis of the sagittal view, which demonstrates inadequate bone height to accept a dental implant without impinging into the maxillary sinus cavity.

Implant placement and tenting began with proper angulation mesial-distally using a 2.4-mm-diameter pilot bur. This bur initiated the osteotomy. Thinking tooth-down, an 8-mm-wide maxillary molar tooth replacement was planned. Thus, placement was approximately 4.0 mm distal to the adjacent tooth. Knowing that there was minimal bone height available, the pilot bur was only positioned about 4.0 mm into available hard tissue, or approximately 1.0 mm short of the assumed floor of the sinus. (Figures 2 and 3). The soft tissue in this site was about 2.0 mm thick. A flapless procedure was chosen here, and the pilot bur position was easily visualized at 6.0 mm at the soft-tissue level. There was no penetration into the sinus cavity, which was verified digitally and with a periapical radiograph. Verification was done using the measuring tool on the DEXIS system.

|

To widen the osteotomy, a 3.0-mm-diameter Hahn (Guided Surgical Kit [Glidewell]) bur was positioned 8.0 mm to the soft-tissue level and verified and measured with a periapical radiograph. Again, there was no penetration into the sinus cavity at this point (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 6 demonstrates the use of a surgical punch that was used to remove the soft tissue from the osteotomy site. This clean, concise incision eliminated the possibility of soft tissue infiltrating our osteotomy site and reduced postoperative discomfort since we were only incising the attached gingiva.

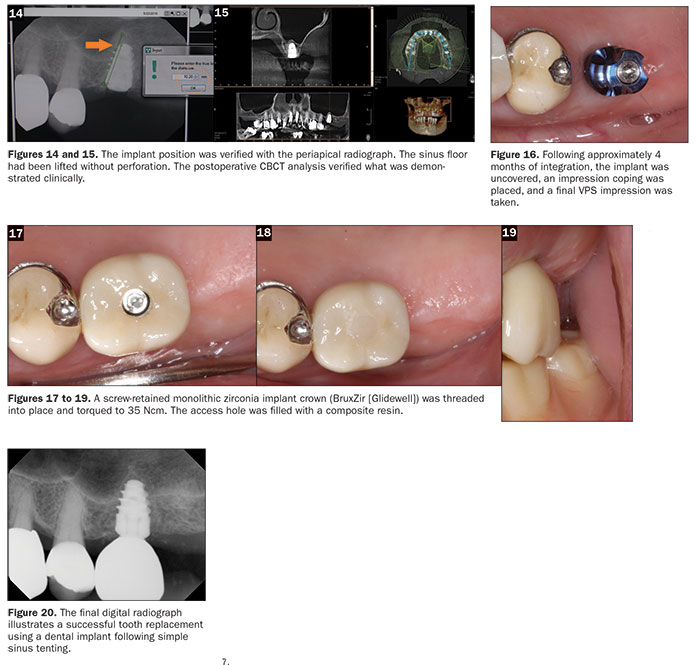

At this point, no longer was hard tissue removed with our osteotomy burs; rather, a series of osteotomes were used to widen the osteotomy site, condense the available medullary bone, and lift the sinus floor without penetrating through the Schneiderian Membrane. Verification of proper position, both mesial-distally and vertically, was done by taking a periapical radiograph (Figures 7 to 9). The osteotomy was widened to the established depth with wider osteotomes. The site was now ready for grafting using a resorbable membrane shaped a bit wider than the created osteotomy and allograft material (Newport Biologics). This membrane was lightly placed into the established surgical site, and the final osteotomes were used to lift the sinus floor (Figures 10 and 11). The Hahn Tapered Implant System (Glidewell) was then threaded into place using a torqued wrench (Glidewell). The tapered body of the Hahn implant was an ideal choice in this situation. It has prominent buttress threads that widen at the apex. This design helps in creating excellent stability of the implant in the osteotomy site. The self-tapping grooves of the thread pattern create effortless placement, and the microthreads on the coronal portion help in the preservation of crestal bone. Figures 12 and 13 demonstrate that a final torque of 45 Ncm had been established, clinically indicating sufficient initial stability of the implant in this medullary bone. The implant position was verified with the periapical radiograph. The sinus floor had been lifted without perforation. The post-op CBCT analysis verified what was demonstrated clinically (Figures 14 and 15).

Following approximately 4 months of integration, the implant was uncovered. Then an impression coping was placed, and a final impression was made using vinyl polysiloxane impression materials (Panasil Putty Soft and Panasil initial contact medium [Kettenbach LP]) (Figure 16). A screw-retained monolithic zirconia crown (BruxZir [Glidewell]) was threaded into place and torqued to 35 Ncm. The access hole was then filled with a composite resin (TPH Spectra [Dentsply Sirona Restorative]) (Figures 17 to 19). The final digital radiograph (Figure 20) shows a successful tooth replacement using a dental implant following simple sinus tenting.

CLOSING COMMENTS

The technique demonstrated herein involved the placement of an allograft material in a relatively non-invasive way. The sinus floor was elevated by pushing through a small hole created by punching the soft tissue. This relatively non-invasive surgical procedure ensures proper angulation and placement of a modern dental implant and provides adequate bone density to allow for initial implant stability and eventual osseointegration over time. This is a very controlled procedure within the realm of the general practitioner. However, it is imperative that, when doing this one-stage grafting and immediate implant procedure, at least 70% of the implant be seated in the patient’s natural bone, with placement of the apical portion of the implant in the grafted sinus area.7

References

- Summers RB. A new concept in maxillary implant surgery: the osteotome technique. Compendium. 1994;15:152-158.

- Sbordone L, Toti P, Menchini-Fabris G, et al. Implant success in sinus-lifted maxillae and native bone: a 3-year clinical and computerized tomographic follow-up. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2009;24:316-324.

- Riben C, Thor A. The maxillary sinus membrane elevation procedure: augmentation of bone around dental implants without grafts—a review of a surgical technique. Int J Dent. 2012;2012:105483.

- Kosinski TF. Predictable sinus tenting with implant placement. The Profitable Dentist. Spring 2016:32-35.

- Lee S, Lee GK, Park KB, et al. Crestal sinus lift: a minimally invasive and systematic approach to sinus grafting. Journal of Implant & Advanced Clinical Dentistry. 2009;1:75-88.

- Nolan PJ, Freeman K, Kraut RA. Correlation between Schneiderian membrane perforation and sinus lift graft outcome: a retrospective evaluation of 359 augmented sinus. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72:47-52.

- Nedir R, Nurdin N, Szmukler-Moncler S, et al. Placement of tapered implants using an osteotome sinus floor elevation technique without bone grafting. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2009;24:727-733.

Dr. Tilley is a graduate of the University of Alabama School of Dentistry. She is a native of Pensacola, Fla, and has been practicing dentistry in her hometown since 1998. Dr. Tilley keeps up with the latest in dentistry by attending continuing education seminars on topics such as oral surgery, implants, veneers, periodontal disease, cosmetic procedures, and much more. She has also done extensive training at the Las Vegas Institute for Advanced Dental Studies and the Engel Institute with Dr. Timothy Kosinski and Dr. Todd Engel. She is a member of the AGD, ADA, Florida Dental Association, Alabama Dental Association, Academy of Laser Dentistry, International Congress of Oral Implantologists, and the Academy of American Facial Esthetics. She has published extensively on implant dentistry techniques, lasers, and Botox/fillers. She can be reached at stephflynntilley@cox.net.

Disclosure: Dr. Tilley reports no disclosures.

Related Articles

From a Removable Appliance to a Fixed Prosthesis: That’s Just What the Doctor Ordered!

Expanding Diagnosis and Treatment Skills