Electronics in your mouth? It’s not a bad idea, if you’re prone to grinding your teeth or playing football, for instance. Researchers at the University of Florida have developed a smart mouthguard equipped with sensors, enabling a multitude of medical applications.

“It’s easy access to the oral environment. It’s also access to a number of biological markers,” said Dr. Fong Wong, an associate professor in the university’s restorative dental sciences department and craniofacial center.

For example, dentists may see patients with worn, fractured, or even broken teeth and suspect bruxism. These dentists typically would send such patients to a sleep clinic for diagnosis. The mouthguard, however, lets patients stay at home.

Patients put on the guard and go to sleep. Its sensors measure how much force is applied by the jaw as well as which teeth are most affected. The electronics transmit the data to a handheld device like a smartphone or tablet. Wearing the mouthguard each night for several weeks provides the dentist with plenty of real-time information to make a diagnosis.

“Wearing a mouthguard is less intrusive than spending time in a sleep clinic,” Dr. Wong said. “It cuts cost when it reduces the number of clinical psychology sessions.”

Much to the chagrin of many teenagers, orthodontists could use similar sensors with retainers to monitor compliance. Perhaps more importantly, the electronics also could be used someday to monitor glucose in diabetics and possibly screen for oral cancer.

“Saliva actually has a lot of biomarkers that could be potentially used for monitoring, for treatment, and the mouth has really easy access compared to everywhere else in the body,” said Dr. Wong, who is a maxillofacial prosthodontist and head of the school’s neck and cancer team. “That’s why initially I was approached to be on this project.”

The researchers are developing athletic applications as well. Sensors can be tuned to tell when athletes are getting dehydrated or overheated. They also can detect acceleration and the force behind impacts, which would be a great help in diagnosing concussions.

In fact, the researchers are now working with a high school football team to test out these applications. They also have plans to work with the University of Florida football coaching staff when training camp starts next spring.

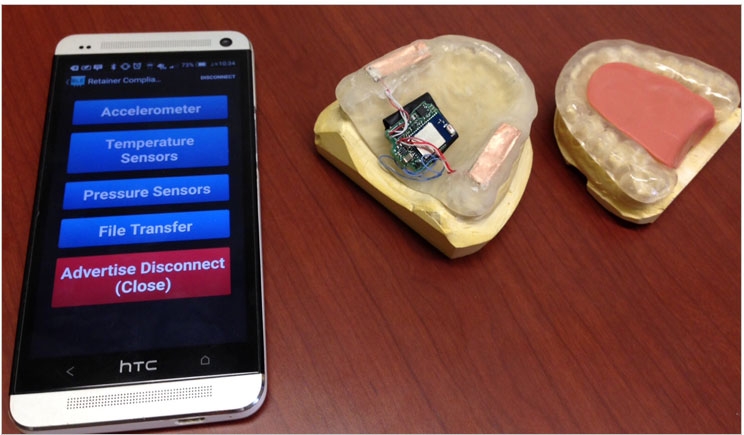

The researchers used commercially available materials to produce the mouthguards, which they crafted for upper mold comfort and durability. While the area where the electronics is embedded is thicker than the rest of the mouthguard, the researchers (who have tried the guards themselves) say the guards are still comfortable to wear.

The electronics have evolved since the smart mouthguard was first conceived. They began with a chip package that was about 2×2 cm2. That package is now 1×1 cm2 and fits in the sidewall of the mouthguard near the molars. The battery, also 1×1 cm2, fits in the sidewall near the opposite molars.

“We just found that kind of size and scale should be a balance in terms of size,” said Dr. Yong-Kyu “YK” Yoon, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at the university. “We intentionally chose a battery that was very similar in size to the electronic chip set.”

The rechargeable lithium-polymer battery lasts at least 24 hours. The researchers say that’s more than enough for 8 hours of monitoring someone who is asleep or for use by a football player during an actual game. Recharging takes about 10 to 15 minutes.

One version of the package has 11 sensing nodes. Models designed for concussion detection rely on a 9-axis inertia sensor with a 3-axis accelerometer, a 3-axis gyroscope, and a 3-axis magnetometer. Other sensors detect factors such as temperature, acceleration, and even heartbeat.

“When you are exercising, your heartbeat is very high, and your moisture is very low. This is an indication of dehydration,” Dr. Yoon said. “But then there could be a low heartbeat and your temperature is very high. It might be that you’re simply drinking a hot beverage.”

For protection from the mouth’s hostile environment, the sensors are packaged in durable yet dental-compatible materials such as poly methyl methacrylate (PMMA) and ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA), depending on the application.

“Many commercial mouthguards use EVA material, so we seal the electronics in it,” Dr. Yoon said. “You can prevent water intake through the material for 24 hours. There is not sufficient time for saliva to get through the polymer and reach the electronics.”

Using Bluetooth, the electronics broadcast the information to a handheld device or to a PC. The researchers chose Bluetooth instead of other wireless protocols like Wi-Fi because it provided the best ratio of data rate to power consumption. The handheld device or PC then runs an app that presents the data for the physician or coach to interpret.

“Our group members are very good at programming, so we made our own app,” said Dr. Yoon. Currently, the app is compatible with Android devices, though Dr. Yoon notes that they plan on developing an Apple version as well.

Dr. Yoon and 3 of his PhD students are leading the effort on the electronics side of the project, while Dr. Wong is focused on the dental and medical applications. Work on the guard began about 5 years ago as part of one former student’s thesis. That student is now working at Apple.

The guard already has won second place at the International Contest of Applications in Nano/Micro Technologies in Anchorage, Alaska, earlier this summer. In October, the team will take it to the Global Innovative Use Festival in Beijing. And they couldn’t resist Las Vegas either, with an appearance at the 2016 International Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in January.

“That is one of the big steps,” Dr. Yoon said. “We are ready to attend that one, but we have some minor improvements, especially the software interface, which should be improved for that.”

The researchers expect other tweaks, too. The electronics could get even smaller, and the battery could be made to last longer. The transmitter’s range could be increased, too. Plus, the sensors could be adapted from football applications to other sports like boxing or hockey.

“Depending on the different sports, we don’t have to have 11 or 12 different sensors,” Dr. Yoon said. “Some applications may need a very simple sensor, or some other ones may need more sensors. Each sport has different requirements.”

Looking ahead, the researchers will present the technology to the university’s institutional review board. Also, while the dental applications may require approval from the federal Food and Drug Administration, the sports applications won’t. If all goes well, the researchers hope for commercialization next summer.

“We are going to conduct testing, and then we will try to publish the data. Once it’s reliable and we know which data is meaningful, we will definitely commercialize,” said Dr. Wong. “We are looking for partners right now.”