Acute pain is the most common complaint that causes patients to seek help from healthcare professionals. Pain management remains an important consideration in dental care and patient management. Although utilized for acute pain control, analgesics provide significant anti-inflammatory effects. Anti-inflammatory analgesics are available both over-the-counter (OTC) and by prescription. Since analgesics are widely used in dentistry and by patients for other medical indications, the dentist should be knowledgeable in their pharmacology. This article thoroughly reviews these drugs including mechanisms of action, indications, dosage regimens, and drug interactions. A suggested pain management plan is provided.

DEFINING PAIN

|

Pain, as defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain, is “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage.”1

ACUTE PAIN MANAGEMENT

The majority of dental pain is an acute response to inflammation. The acute pain associated with dental trauma, infection, or surgery is usually predictably managed pharmacologically. The key to pharmacologically managing pain is to provide a sufficient dose of a particular drug to minimize pain onset and give the patient comfort. The drug should be administered frequently to prevent the pain from becoming severe. The most effective way to maintain analgesia is to administer doses on a regularly scheduled basis for a specified period after the trauma. For example, after periodontal surgery, inflammation and pain usually peak 48 hours later. Thus, postoperative analgesic medication can be administered on a regular schedule, depending on the half-life of the drug (eg, every 4 hours), for 48 hours, then given as necessary (prn).

CLASSIFICATION OF ANALGESICS

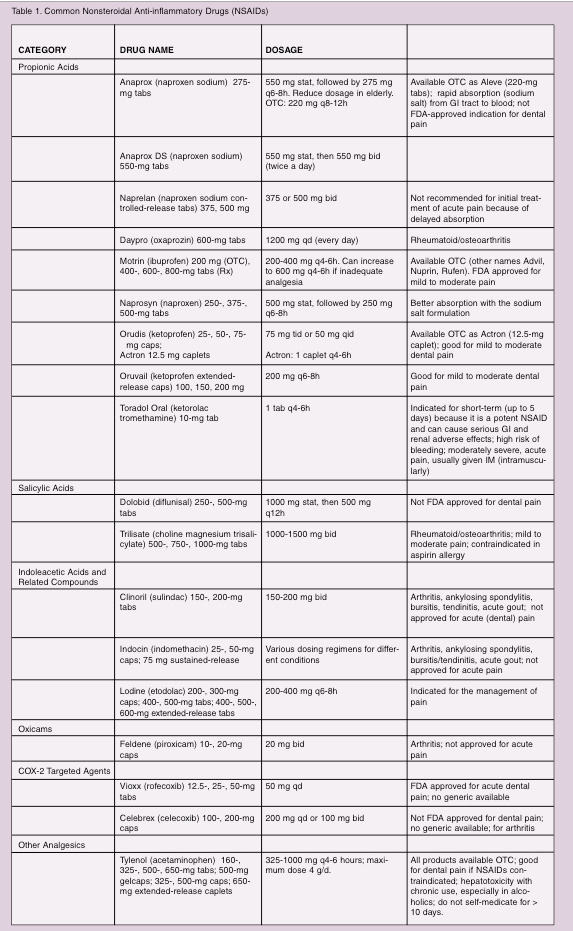

Analgesics are classified as antipyretic analgesics, nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) selective NSAIDs, and opioids.

Antipyretics

Acetaminophen is an antipyretic analgesic with no real attributable anti-inflammatory effect. Its mode of action has never been totally determined. It is provided as an oral or rectal dose form. Although acetaminophen is eliminated through the kidneys, part of the therapeutic dose is broken down in the liver. However, doses in the excessive range of 10 g can cause hepatic damage. Also, consumption of alcohol and acetaminophen can cause liver damage. Overdosing is not difficult, as the patient may not be cognizant that other OTC products contain acetaminophen. The maximum recommended dose is 2 to 4 g daily.

|

The analgesic potency of a NSAID is largely related to its ability to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis. NSAIDs block prostaglandin production by the inhibition of the COX enzyme in the arachidonic acid pathway. Two forms of COX have been identified. The constitutive form (COX-1), which is present in most tissues, including the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, kidneys, and platelets, plays a protective role in these organs. The inducible form (COX-2) is found in small amounts in inflammatory cells (macrophages), endothelial cells, synovial cells, and chondrocytes (unless an inflammatory process is occurring).2 Inhibition of COX-2 in these tissues is probably responsible for the anti-inflammatory effects of NSAIDs. Each NSAID inhibits COX-1 and COX-2 to varying degrees. The inhibition of COX-1 causes undesirable effects including gastric complications, depression of renal function, and inhibition of platelet aggregation. This inhibition of platelet aggregation is dose/drug dependent. Aspirin and nonselective NSAIDs exert their antiplatelet effect by inhibiting COX which blocks the formation of thromboxane A2. When a NSAID comes into contact with the platelet cell membrane, it binds to and inhibits the release of COX, thereby altering platelet function. The antiplatelet effect of aspirin is irreversib

le, lasting for the half-life of the platelet (approximately 7 days). However, NSAID derivatives reversibly bind to the platelet membrane causing a transitory antiplatelet effect. Recovery of platelet function may occur within 1 to 4 days after discontinuation of the drug.

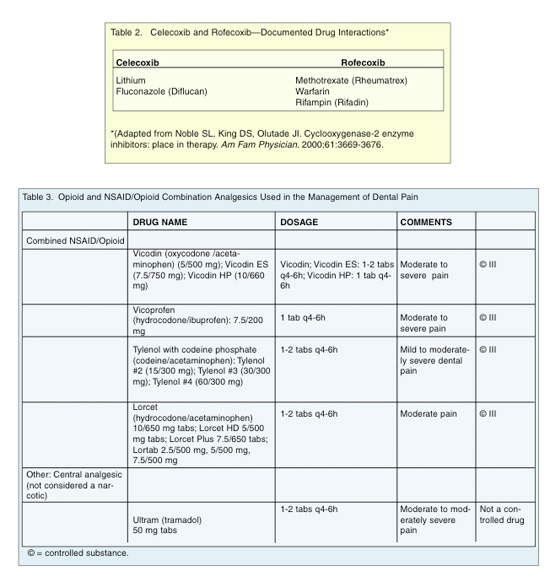

COX-2 NSAIDs

The most recent advances in NSAIDs have been the development of selective COX-2 inhibitors. An advantage of these NSAIDs is a more favorable GI, renal, and platelet side-effect profile. Rofecoxib (Vioxx) is FDA approved for acute pain (including dental pain) in adults, primary dysmenorrhea, and osteoarthritis.3 Celecoxib (Celebrex) is only FDA approved for the long-term treatment of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis and not for acute dental pain. Thus, rofecoxib is a good choice for patients with prior or present GI problems.

ADVERSE SIDE EFFECTS/CONTRAINDICATIONS TO NSAID USE

Because serious GI effects have been associated with nonselective COX inhibitors, these medications should be avoided in patients who present with a history of peptic ulcer disease or GI bleeding. Additionally, all NSAIDs are highly protein-bound and have the potential to displace coumadin and potentiate its anticoagulant effect.

|

Along with the analgesic effects, all opioids have similar profiles of toxic side effects, which should be considered when prescribing these medications. Respiratory depression may occur in a patient taking an opioid for the first time. Tolerance to opioids can develop over time so that regular increases in the dosage may be required in order to provide a sustained analgesic effect. However, side effects will continue to occur including constipation, sexual impairment, and nausea. Opioids can create a physical dependence and addiction, which is termed a psychological loss of control resulting in compulsive use. Opioids may cause sedation and/or drowsiness.

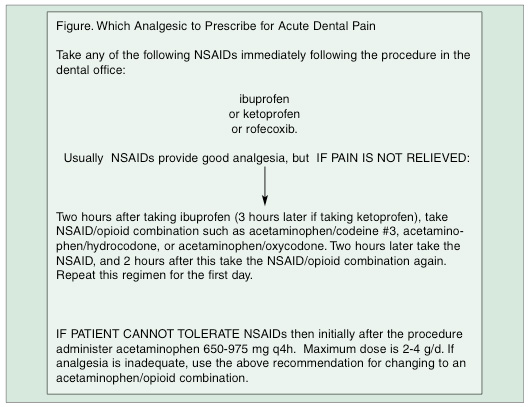

SELECTION CRITERIA: DECISION TREE FOR MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE PAIN

A decision tree (Figure) is proposed for the management of acute dental pain. Initially, a maximally effective dose of a NSAID should be prescribed, (eg, rofecoxib, ibuprofen, or acetaminophen), with the patient ingesting the loading dose in the office.

her advantage to dosing after an invasive procedure is to avoid the effects of inhibition of platelet aggregation.

References

-

Mersky H. Pain terms: a list with definitions and notes on usage, IASP Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain.

-

Fu JY, Masferrer JL, Seibert K, et al. The induction and suppression of prostaglandin H2 synthase (cyclooxygenase) in human monocytes. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16737-16740.

-

Matheson AJ, Figgitt DP. Rofecoxib: a review of its use in the management of osteoarthritis, acute pain and rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs. 2001;61:833-865.

-

Ament PW, Bertolino JG, Liszewski JL. Clinically significant drug interactions. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:1745-1754.

-

McEboy GK, ed. AHFS Drug Information 2001. Bethesda, Md: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2001.

-

Noble SL, King DS, Olutade JI. Cyclooxygenase-2 enzyme inhibitors: place in therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:3669-3676.

-

Moore PA, Hersh EV. Celecoxib and rofecoxib. The role of COX-2 inhibitors in dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:451-456.

-

Agency for HealthCare Policy and Research. Acute Pain Management in Adults: Operative Procedures. Rockville, Md: Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1992: AHCPR Publication no. 92-0019.

-

Carpenter RL. Optimizing postoperative pain management. Am Fam Physician. 1997;56:835-844, 847-850.

-

Vogel RI, Desjardins PJ, Major KVO. Comparison of presurgical and immediate postsurgical ibuprofen on postoperative periodontal pain. J Periodontol. 1992;63:914-918.

- Dionne RA, Cooper SA. Evaluation of preoperative ibuprofen for postoperative pain after removal of third molar. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1978;45:851-856.

Dr. Weinberg is clinical associate professor of periodontics and director of the second-year periodontic program at New York University College of Dentistry, David B. Kriser Dental Center in New York. She is a member of the American Dental Association. Dr. Weinberg can be reached at (212) 998-9506 or maw2@nyu.edu.

Dr. Fine is presently associate professor of clinical dentistry and postdoctoral director of the Division of Periodontics at the School of Dental and Oral Surgery of Columbia University and associate attending dental surgeon on the Presbyterian Hospital Dental Service. He is a diplomate of the American Board of Periodontology. Dr. Fine has served on the Research, Science, and Therapy Committee of the American Academy of Periodontology, and has been the recipient of several teaching awards and fellowships. He has authored or coauthored numerous articles in the periodontal literature, and was an author of the text, Clinical Guide to Periodontics. He can be reached at ms14@columbia.edu.