The fully seated dental operating position combined with the air turbine handpiece ushered in what has been known as the golden age of dentistry. This increase in capacity, along with the baby boom, launched a rise in dental incomes and formed the foundation for success of the dental profession as we know it. For today’s health conscious practitioners these innovations are also important for having helped reduce the number of practice-induced “hunchbacks” in the later stages of a professional career. Perhaps you have noticed these poor older practitioners at your last dental meeting (Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. Early sitting techniques did not usher in a significant improvement in operator ergonomics. |

Unfortunately, most in the field treated these great technological successes as the end of the journey, as we turned our attention to the other great opportunities our blossoming profession has created. Scientific effort was transferred to ancillary devices (such as curing lights, resins, intraoral cameras, etc) that served to broaden the scope of services, further stimulating the profession’s ascendance. Today, a general dental practitioner’s income is greater than that of a family physician’s.

However, this success is not without its problems. Low back pain is the leading cause of occupational disability in dentistry. Studies clearly show that low back pain is frequently related to sitting duration. When sitting was first introduced to dentistry, most dentists spent their day doing amalgams. The procedures were fast and easy. Today, with the wide range of services offered, many practitioners find themselves in a fixed seated position for extended time periods—a situation that is extremely deleterious to the spine and to physical health in general.

The evolution to the seated position is just the beginning of our journey. A new look at dental practitioner positioning must occur as we pursue greater performance, and as a result, incomes comparable to other surgical professionals, behind which we currently lag. In order to discover how to minimize problems protracted sitting causes and gain the maximum benefit from the advantages sitting offers, it would be helpful to know a bit more about the spinal column—how it works and how spinal health relates to sitting.

Many experts in the field believe sitting is, in fact, not a particularly healthy position, but that it just happens to be the most practical position from which to operate machines. Some, such as Dr. Galen Cranz of the University of California, have argued that in preindustrialized society the seated position existed solely for ceremonial purposes. Many civilizations, such as Japan and India, did not utilize chairs throughout thousand of years of their development.

The human spine and its support musculature is a living structure that benefits from movement. Our shock-absorbent disks must have motion in order to be nourished properly. Any attempt at physically constraining the spine in a so-called “proper position” will ultimately meet with failure. If there can be no perfect position, by definition there can be no perfect chair. The best chair will be the seat that in the context of the task to be performed minimizes the damage done by sitting while allowing its occupant to transition through the hundreds of postures, all of which vary in their level of imperfection.

So, if the seat is our best hope for a productive dental practice and yet it still has the potential for damaging our health, how should we study and improve sitting? What are the criteria for a great operator stool?

|

|

| Figures 2a and 2b. Improper positioning and poor stool selection encourages stressful practice habits. | 2b. |

Beginning with training in most dental schools, the young practitioner learns to accommodate to institutional equipment often purchased primarily for its price and durability or as part of a complete equipment package. Support, the reason for a chair’s existence, is relegated to a position of minor importance, or worse, ignored (Figures 2a and 2b). After graduation, when faced with the expense of an office start-up, many items supersede the young practitioner’s attention to seating. Worries about the cost of x-ray machines and handpieces, as well as attracting patients, easily overshadow concerns about a place to sit. And so the limber young professional begins a career filled with awkward positions day in and day out. It seems that ergonomics, and with it proper seating, only emerge as priorities once discomfort or injury encroach, thus adding the need for a chair to rehabilitate as well as support the practitioner.

While it is to a certain extent true that there are a wide range of apparent seating preferences, these preferences break down into a limited number of discrete characteristics. If you know where you want to go, it is without question easier to determine how to get there. Just as a bed is your most used and thus most important piece of household furniture, so should the operator stool be at the center of your office ergonomic purchasing plan, because its contact and use shapes the overwhelming percent of your day.

Let’s begin to look at the ideal operator’s stool from the ground up in order to ensure the support that is right for you and your practice. Follow-ing are 8 keys to selecting the proper stool.

NO. 1: CAST STAR BASE CONSTRUCTION WITH HIGH-QUALITY CASTERS AND BEARINGS

There is no clerical office task that requires as much micromotion as does clinical dental practice. The dental stool moves almost every minute as the operator adjusts to improve visual access and as he or she accommodates patient movement. Casters must be able to respond rapidly to these requirements. In addition, the support base itself must bear the repeated stress of an operator’s continuous chair entry and exit over years of function. A dental stool should, therefore, be constructed using a rigid cast framework that will not distort with time and use. A 1-piece casting is less likely to distort and thereby rock with time. This rigid base must accommodate 5 casters to prevent rearward tipping; however, the base should not be as wide as that of many office chairs. Dental stools must have a compact base so that the wheels do not interfere with the feet, the foot controls, or the patient chair.

NO. 2: FULLY ADJUSTABLE HYDRAULIC GAS LIFT

|

|

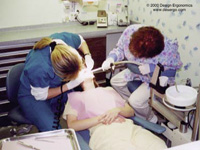

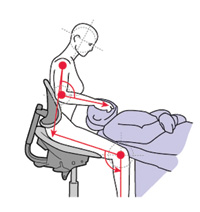

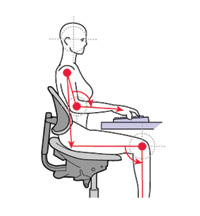

| Figures 3a and 3b. A wide variety of postures are ergonomically acceptable and provide for great practitioner flexibility. | 3b. |

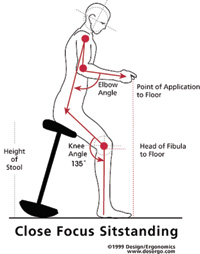

During the workday, dentists are confronted with a wide assortment of patient sizes and restrictions. These variations should not cause the level of operator stress and strain that dentists seem to believe they must. In order to accommodate this wide range of sizes, shapes, and positions, a dental operator stool must have a hydraulic piston assembly that allows the widest range of motion. It is recommended that a shorter operator have a stool adjustment range from 16 to 21 inches and a taller individual have a range of 21 to 26 inches. Dental assistants need to be able to function from 20 to 31 inches, depending on doctor height. In most North Amer-ican dental offices, the assistant will sit at least 4 inches higher than the doctor in order to ensure a clear sight line to the oral cavity. While virtually none of the operator seats on the market cover a range of 16 to 26 inches, a limited number of specialty dental stools will accommodate most of this range of motion. In an ideal situation an operator should be able to function from a height range where thighs are parallel to the floor through a full legsupported position referred to as “sit-standing” (Figures 3a and 3b). Sit-standing is especially useful for posture-compromised patients who are unable to lie back in a full re-cumbent position, and on occasion, when dealing with highly apprehensive individuals.

NO. 3: TRUE WATERFALL-STYLE SEAT SUPPORT

|

| Figure 4. Waterfall seat front. |

Today it seems that every product that touches our lives is being described as ergonomic. All too often, this ergonomic claim is due to some minor modification, or worse, simple relabeling of a product. In seating, we see the softening of a chair’s leading edge being cause to suddenly create a so-called ergonomic seat. A soft seat front does not make an ergonomic chair. True ergo-nomics must generally be built into a product, not just tacked on (Figure 4).

|

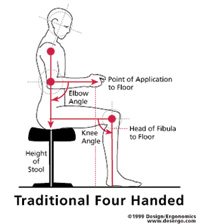

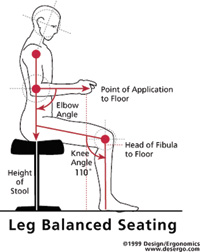

| Figure 5. Leg-balanced sitting provides traditional support. |

True waterfall design, while just one of a number of concepts in ergonomic seating, is an essential principle. Your chair must be designed so that the seating position can be slightly elevated beyond the parallel without restricting blood flow to the legs. This allows an operator to maintain a forward and upward posture while operating and transfers some of the body’s support to the feet. We refer to this as “leg balanced sitting” (Figure 5).

NO. 4: RAPID AND EASY-TO-USE ADJUSTMENTS

|

|

|

Figure 6a. Complex adjustments should be reserved for those

situations where it is unavoidable.

|

Figure 6b. Single-lever, 3-way adjustability with separate back height adjustment. |

All too often, we are led to believe that more complexity results in an improved product. In reality, nothing could be farther from the truth. Studies in many industries have shown time and again that users need both adjustability and simplicity in the products they use. Your seating must be rapidly and easily adjustable by all users. Complex mechanisms will rarely be used in the way they are designed to be. The simplest fully adjustable mechanisms have a single lever that activates both height and base tilt while allowing back height to be adjusted directly at the backrest (Figures 6a and 6b).

NO. 5: STRONG FORWARD BASE-TILT CAPABILITY

|

| Figure 7. Strong forward tilt of the seat is a unique requirement for dental operator stools. |

Dental health workers do not operate from a position that is in any way equivalent or similar to that of typical clerical office workers. Dentists are universally subjected to a forward (and hopefully upward) proclination. The seat support mechanism required must reflect this special circumstance. It must be forward adjustable to remind the operator’s lower back to maintain its natural curve. This reminder is more important than the seat back actually supporting the operator. If you think about this for a minute, you can’t really support someone from behind if they are leaning forward! Most so-called dental stools do not allow this posture and instead are vinyl-covered variants of basic office seating. Correct dental seating should allow an individual no less than 20° of positive forward support. Adjustment should be quick and accommodate a wide range of postures (Figure 7).

NO. 6: STRONG LUMBAR SUPPORT WITHOUT SHOULDER IMPINGEMENT

|

| Figure 8. Deep lumbar support with freedom at the shoulder. |

Dentists are not sitting in treatment rooms to read books or take naps, yet all too often purchasing decisions are made based on a seat’s apparent comfort at a trade show or dental showroom—away from patient treatment. As a result, operators often will select a seat better suited for the private office than the operatory. The lumbar mechanism should allow an adjustment range that positions the lumbar support well into the operator’s low-back curvature (Figure 8). The backrest should not be so tall as to prohibit the natural curvature of the spine. Many contemporary operator stools are equipped with a backrest that is far too tall and wide to allow operator motion flexibility. This can interfere with shoulder mobility. Excessive width is an additional problem that prohibits close work from the 7 o’clock position.

NO. 7: FIRM, SUPPORTIVE SEATING SURFACES

|

| Figure 9. A firm, contoured seat permits support during lateral motions. |

As dental providers, we sit on a stool for balance and support. Thick padding that may feel elegant during a demonstration prohibits maximal extension laterally during dental use. Unlike office workers, we must frequently function off-axis. Only a contoured seat firmly padded with the highest quality foam core is able to permit this motion safely (Figure 9). A softer padded seat that has contour built into the pad rather than the base gives way during lateral reach motions and re-quires the operator to strain during extension.

NO. 8: OPTIONS FOR PERSONALIZATION

While arm support is a controversial subject, many operators and experts feel they are essential to health and comfort. Some physiologists believe that lack of adequate arm support is a primary contributor to thoracic outlet syndrome and carpal tunnel, though this has not been clearly demonstrated. The capability to add highly supportive arms that function through a wide range of motion is an option that any modern dental stool should provide.

|

| Figure 10. Unique, fully articulating elbow rests. |

When a dental stool is outfitted with arm support, the arms may be fixed in length but must allow rapid height adjustment and full articulation. If you find yourself leaning on nearby cabinets or resting your arm on your patient’s head, then you need a new stool, a new position to practice from, and possibly support arms (Figure 10).

CONCLUSION

The dental operator stool is a most vital and often neglected piece of dental technology. It is a lifeline to long-term practitioner health and productivity. Perhaps no dental acquisition is more personal than this purchase. Choose wisely for a prosperous and healthy future.

Dr. Ahearn is the founder of Design/Ergonomics (design-ergonomics.com), a design and consulting group that creates high-performance dental office designs and consults with doctors and universities regarding productivity constraints. He can be reached at (508) 636-3600 or djahearn@desergo.com.