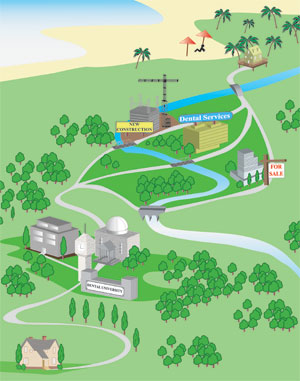

In my educational workshops I talk a lot about the importance of life planning: the idea that dentists need a comprehensive plan that integrates practice and personal economics within the context of a clear vision (Figure). It always amazes me how this simple concept resonates so deeply with many very successful practitioners. I am often approached by dentists who say they feel a “void” despite years of practice and that they want to rediscover their passion for dentistry…and for life. There is a real need in our industry to bring clarity, passion, and engagement back into the lives of dentists who are successful, but unfulfilled; busy, but feeling incomplete; established in their careers, but looking for a way out.

Is the profession really that bleak? I don’t think so. I know many practitioners who are absolutely in love with dentistry and would not choose any other business in which to be. But could it be better? I am 100% sure that it can be. In fact, I am so convinced that this profession is among the best that I have devoted my career to helping dentists see what is possible in dentistry and giving them a plan to achieve their practice and personal goals.

Most of us start out full of hope and possibility, but then let circumstances interfere along the way. The primary reason for choosing dentistry as a career, according to a 2001 survey1 of dental students, was the “ability to control time at work in relation to personal and family interests.” “Service to others” and “self-employment” was tied at second. They may be young, but the dental students in this survey were right on! I don’t know of another profession that offers the entrepreneurial flexibility and personal fulfillment that dentistry does, and with almost no upper limit to the amount of income one can earn.

|

|

Illustration by Brian Green

|

THE LIFE CYCLE OF A DENTIST

So where along the way does this clarity get lost? Why do only some practitioners actually experience all that dentistry has to offer? It is easy to see how it happens. After graduation, most new dentists go into what I call “survival mode,” with their sole objective being to find and acquire a practice by starting from scratch, joining an existing practice, or purchasing one outright. They make personal and financial sacrifices willingly in an effort to make a small dent in their huge accumulation of school and practice debt, as well as to hone their fragile clinical skills in a trial-by-fire fashion. In short, they exist only to get through each day and hope the next is a little easier, a little more profitable, and a little more fun.

Somewhere along the line, these young practitioners gain their footing, and the focus turns to growing their practice. Demands of practice ownership still require some personal sacrifices. Paying down debt remains a priority, but often profitability will have reached a point where personal economics are less strained. Dentists in this phase are often still working long days, and some struggle to balance the added commitments of a growing family.

As they become further established in practice and more comfortable with the demands of ownership, many dentists start looking for ways to balance their work commitments with more time for family and vacation. The practice may be “successful” by this point, but it does not run by itself.

Often, mid career dentists begin to worry about future economic realities, such as paying for a child’s education and funding their own retirement. They must also continue to invest in their practice and clinical skills in order to remain current and competitive.

This “established” phase can go on for years, and for many dentists it takes them right up until the twilight of their career. With the realization that they cannot practice forever, many begin looking for exit solutions, only to find that the scarcity of graduating dentists does not favor the selling doctor and that their practice value falls short of fully meeting their retirement needs. Notwithstanding their economic needs, these dentists often have a staff and patients who are also approaching retirement, and they feel an obligation to continue to practice long after they reach burnout.

I have purposely painted a rather dim picture here of the life cycle of a dentist, not because it is like this for everyone, but because I have seen far too many practitioners go through their careers in this way. They hide in their comfort zone year after year, and before they know it, decades go by. It is a life dominated by worry: they worry about paying down their school debt and then about paying off the loans from the purchase of a practice. They worry about affording their children’s education, and then about whether they can afford to retire. They worry about the daily realities of running a practice—not enough patients, not enough time (or too many patients, too much time)—and they worry about the things they don’t have time to worry about—keeping their facility current, maintaining team alignment, and making time to improve their clinical skills.

If I have learned one thing in 25 years helping dentists, it’s that it does not have to be this way. It’s not only possible to have the life in dentistry you envisioned as a dental student, it’s actually easier, more profitable, and more fun to do so. And that is what life planning is about for me. Its about asking the question, “If I could have it any way I wanted it, how would it be?” and then working backward through a series of further questions until you arrive at a plan that allows for choices and freedom in every phase, choices that protect your future at the same time. A life plan replaces anxiety with peace of mind, burnout with passion, and unhealthy stress with a healthy tension between what is and what can be.

THE LONGEVITY FACTOR

There is another central flaw in the life cycle of a dentist. The established practitioner that I talked about will likely reach his comfortable plateau sometime in his forties, at which point practice growth has slowed or leveled off completely. A generation ago, retirement at age 55 or 60 would mean this dentist could “coast” comfortably for 10 to 15 years before closing his doors for good. Today, however, demographic and economic factors make this scenario impossible.

As the average life expectancy creeps well into the 80s for both men and women, and as medical advances continue to accelerate at unprecedented rates, we have additional reasons to think about having a comprehensive life plan. The Employee Benefit Research Institute estimates that a typical husband and wife will need $295,000 to cover out-of-pocket healthcare costs after retirement, assuming an average life expectancy (82 for men, 85 for women). Should the couple live to be 95, they will need $550,000. And remember, this is not about luxury and lifestyle; we are just talking about covering basic healthcare costs.

But let’s forget economics for a minute. Living longer (and healthier, for the most part) also means that retirement at age 65 could leave you with 25 years of blank pages in your date book. That is a long time to do nothing! In fact, a recent survey showed that 7 million previously retired Americans returned to work after an average “hiatus” of just 18 months. About one third returned because their economic position could not support their retirement, but most did so by choice, probably because they needed to do something that continued to give meaning and purpose to their lives.

The reality is that we are living longer, and most of us will need to work longer. Assuming that part is a given, we now get to choose how we spend those working years. With proper planning, it is possible to continue to earn income long into your 60s and even 70s without sacrificing the lifestyle expectations that you have for those years. Having a life plan in place allows you to start making choices about how you work long before you get to the established phase of your practice. That’s when the question shifts from “When can I retire?” to “How long can I stay?”

Note: In Part 2, to be published in next month’s issue of Dentistry Today, the author will discuss the nuts and bolts of a comprehensive life plan, and how asking yourself the right questions can lead to a discovery process that will bring you peace of mind now and into the future.

Reference

- Balachovic RW, Weaver RG, Sinkford JC, et al. Trends in dentistry and dental education. J of Dent Educ. 2001;65(6):549.

Mr. Manji is founder and CEO of the Scottsdale Center for Dentistry, the continuation of his longtime goal to provide a world-class facility where dentists and teams can receive comprehensive, evidence-based, patient-centered learning. For more than 20 years, he has been educating and motivating dentists across North America. Mr. Manji’s newest workshops, Dental Office Design, BreakThrough Practice, and CEREC Experience, and his classics, Leadership & Team Alignment and Transitions & the Business of Dentistry, combine his endless energy and inimitable style with his practical teachings to make these programs a “must-see.” He can be reached at (866) 781-0072 or imtiaz.manji@scottsdalecenter.com.