Any instrument or piece of equipment used in the mouth is a potential source of cross-infection. In addition, dental prostheses, appliances, and items used in their fabrication or repair (eg, impressions, occlusal rims, bite registrations, burs, and stones) are also possibly infectious. Handling such items must be in a manner that prevents exposure of dental healthcare practitioners (DHCP), patients, and the practice environment to infectious agents.1-3

Determining all infectious patients from medical histories, physical observations, and conversations is not possible. Therefore, the only valid posture is to assume (and to act as if) all patients are capable of transmitting highly infectious diseases. The dental team must use the same set of criteria and techniques in all cases.

PRACTICE/LABORATORY RELATIONSHIPS

Effective communication and coordination between dental laboratories and practices will help ensure the performance of appropriate cleaning and disinfection procedures, that damage to materials does not occur, and unnecessary duplication of effective methods does not happen. If contaminated items were to enter the laboratory environment, this could lead to the spread of contaminants to the prostheses and appliances of other patients. This could also place unsuspecting laboratory personnel at increased risk for cross-infection.1-3

When sending a laboratory case off site, DHCP should provide written information regarding the methods used (eg, type of disinfectant used and exposure time) to clean and disinfect an item (eg, impression, stone model, or appliance). In addition, clinical materials not properly decontaminated are subject to OSHA and US Department of Transportation regulations concerning transport and shipping of infectious materials.1

All items coming from the oral cavity must be sterilized or disinfected properly before work starts in the laboratory and then again prior to their return to patients. Communication between the laboratory and the dental practice must identify which party will be responsible for the final disinfection process. Asepsis procedures vary for each type of dental material. However, general recommendations as to procedures and materials are possible.1-3

If the dental laboratory provides disinfection, the use of an EPA-registered, intermediate-level disinfectant is required, written documentation of the disinfection method must be provided, and the item should be placed in a tamper-evident container before returning it to the dental office. If provision of such documentation is not present, then the dental office is responsible for the final disinfection procedures.1-3

Whether in a dental practice or an off-site dental laboratory, wearing of personal protective equipment (PPE) is necessary when handling laboratory cases not yet disinfected. PPE generally includes chemical resistant utility gloves, eye/face protection, surgical masks, and lab coats or clinical jackets.3

RECEIVING AREAS

Dental practices should create separate receiving and cleaning/disinfecting areas to handle all items sent to an off-site laboratory or when dealing with the items in a laboratory within the practice. The area needs running water and handwashing facilities. Impervious paper should cover work areas. Also needed are regular cleaning and disinfection. The amount of cleaning and disinfection depends on the overall usage of the work areas.2

No item (impression or prostheses) should enter the practice’s receiving area unless properly disinfected. Contamination of such items with oral and bloodborne pathogens occurs. Dental prostheses, impressions, orthodontic appliances, and other prosthodontic materials (eg, occlusal rims, temporary prostheses, and bite registrations) need thorough cleaning (removal of blood and bioburden removal), disinfection with an EPA-registered, intermediate-level disinfectant (with a tuberculocidal claim), followed by a thorough rinsing prior to handling in the practice laboratory or being sent to an off-site laboratory.1-3

The ideal time to clean and disinfect impressions, appliances, and prostheses is as soon as possible after removal from the oral cavity before drying of blood and bioburden can occur. If cleaning and disinfection does not completely remove all visible blood and bioburden, then repeat asepsis procedures.1-3

DISINFECTING IMPRESSIONS

There is ample documentation of the transfer of microorganisms onto and into impressions. Organisms can also move into dental casts. Some of these organisms can remain viable for up to 7 days. Again, wearing of proper PPE is required. Incorrect handling of contaminated impressions and casts offers the opportunity for transmission of microorganisms.1-3

There are several steps for properly disinfecting dental impressions:1-3

- after removal from the oral cavity, rinse impressions under running tap water and shake gently to remove adherent water; sometimes soft, camel-hair brushes can help remove debris;

- disinfect impressions using an intermediate-level, EPA-registered disinfectant for the contact time recommended by the manufacturer (usually about 15 minutes);

- after the proper exposure time, the impressions are rinsed under running tap water and gently shaken to remove adherent water; and

- properly disinfected and dried impressions are ready for pouring.

Rinsing helps in the removal of adherent microorganisms. Immersion helps ensure complete contact between all impression surfaces and disinfectant. Immersion can occur in glass beakers, plastic containers, and even zipper-seal bags. Unless specifically approved for reuse, germicides are single-use solutions.1-3

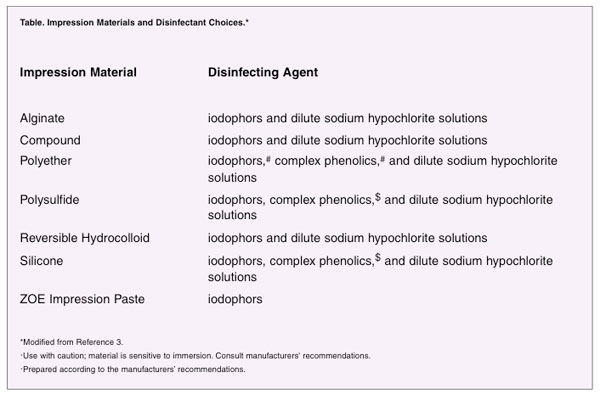

Some types of impression materials are sensitive to im-mersion. Careful selection of disinfectants is required (Table). Spraying has several advantages. Spraying is the treatment of choice for some impression types; it uses less disinfectant and often is the same disinfectant that a practice uses for environmental surface disinfection. Spraying is technique sensitive. Disinfectant must contact all impression surfaces. Spraying also releases disinfectant into the air, thus increasing the chance of personal exposure. Most disinfectants (except glutaraldehydes) are appropriate for spraying.2

Disinfection of impression materials is an area of continuing research. Disinfection in certain types of chemical solutions harms some impression materials. Other types of disinfectants are safe to use on the same impression materials. Research indicates that variations in response within a given type of impression material (eg, alginate) can occur de-pending on the manufacturer.2

DISINFECTING PROSTHESES

Any prosthesis from the oral cavity is a potential source of infection. Most prostheses and appliances cannot withstand standard heat sterilization procedures. An alternative technique would be disinfection by immersion following a thorough cleaning. An intermediate-level disinfectant (tuberculocidal claim) should be used before an appliance is handled or worked upon in the practice laboratory or in an off-site commercial laboratory.2

Some heavily soiled (eg, calculus or adhesive) prostheses require cleaning or scrubbing before disinfection. The most efficient (and safest) pro-cedure is to place the prosthesis into a zippered plastic bag that contains ultrasonic detergent or another type of specialized cleaning solution. The bag is then placed in the chamber of an ultrasonic cleaner. The best cleaning action occurs in the middle of the cleaning chamber. Poorer cleaning occurs near the top and bottom of the solution pool. Bags can also be held in place by allowing the lip to pinch a corner.2

Sometimes further cleaning by hand is required. Air-powdered blasters, such as shell blasters, should only be used on cleaned and disinfected appliances.2

GRINDING, POLISHING,AND BLASTING

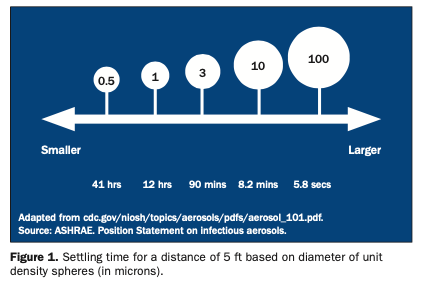

Bringing untreated appliances into a laboratory establishes the potential for cross-infection. Operation of a dental lathe provides an opportunity for the spread of infection and for injury. The rotary action of wheels, stones, burs, and bands generates aerosols, spatter, and projectiles. Whenever using a lathe, the Plexiglas front shield should be in place and the ventilation system operating. The use of masks would be helpful. The air-suction motor should be capable of producing an air velocity of at least 200 ft/min.2

All laboratory items such as burs, polishing points, brushes, rag wheels, stones, and laboratory knives used on contaminated or potentially contaminated materials should be heat sterilized, if possible. If items are heat sensitive and/or do not frequently contact the patient, prosthetic device, or appliance, yet frequently become contaminated (eg, articulators, case pans, and lathes), cleaning and proper disinfection are required. Pressure pots and water baths are especially susceptible to contamination and should al-ways be cleaned and disinfected between patient uses. Many laboratory items now come as single-use, disposable items.1-3

Polishing appliances and prostheses is a necessary activity. To avoid potential cross-infection, several steps are required:2

- using fresh pumice and pan liners for each new case;

- always having the lathe’s protective front shield in place and ventilation system operating;

- obtaining only small amounts (unit doses) of polishing agents (eg, rouge) from larger reservoirs;

- trying to employ single-use, disposable items as much as possible;

- heat sterilizing as many items (including rag wheels, which can be rinsed out and steam autoclaved) as possible;

- properly disinfecting other items; and

- following manufacturer recommendations.

Environmental surfaces are best covered. If not, then they need to be cleaned and disinfected regularly with an EPA-registered, intermediate-level disinfectant. Most laboratory waste can be disposed with the regular practice trash. Sharp items (eg, burs, disposable blades, and orthodontic wires) must be placed into “sharps” containers.2

The Organization for Safety and Asepsis Procedures (OSAP) is dentistry’s source for evidence-based information on infection control and prevention and human safety and health. Further information concerning dental laboratory asepsis is available on the OSAP Web site at osap.org.

References

- Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings – 2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-17):1-66. Also available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5217.pdf. Accessed December 2004.

- Miller CH, Palenik CJ. Infection Control and Management of Hazardous Materials for the Dental Team. 3rd ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby Year-Book; 2004.

- Organization for Safety & Asepsis Procedures. From Policy to Practice: OSAP’s Guide to the Guidelines. Annapolis, Md: OSAP; 2004.

Dr. Palenik has held over the last 25 years a number of academic and administrative positions at Indiana University School of Dentistry. These include professor of oral microbiology, director of human health and safety, director of central sterilization services, and chairman of infection control and hazardous materials management committees. Currently he is director of infection control research and services. Dr. Palenik has published 125 articles, more than 290 monographs, 3 books, and 7 book chapters, the majority of which involve infection control and human safety and health. Also, he has provided more than 100 continuing education courses throughout the United States and 8 foreign countries. All questions should be directed to OSAP at office@osap.org.