Shade communication between the dentist and the laboratory can be a challenge. It is often difficult to communicate the various nuances of color to the technician with a single lab prescription. This is compounded by the fact that human teeth are not one solid color from the incisal edge to the free gingival margin. Our patients do not need a dental degree to see that the color of their restoration is off. They can identify problems with shade just as easily as the dental professional.

The first piece of this puzzle is understanding the science and nomenclature of color. The second piece is to understand what factors influence our perception of color. The third piece is to use this knowledge for predictable, step-by-step shade-taking. The final piece of this puzzle is accomplishing the appropriate amount of reduction for the material selected. Understanding the 4 pieces of the shade-taking puzzle will allow you to choose the appropriate shades for your patients. The desire for predictability in shade selection has led many practices to purchase sophisticated shade-taking devices. Although these devices can be a useful adjunct to your practice, it is important to understand how each of the 4 relevant pieces may improve your opportunity for success.

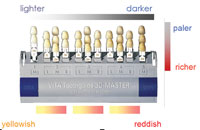

UNDERSTANDING THE SCIENCE AND NOMENCLATURE OF COLOR: HUE, CHROMA, AND VALUE

Hue, chroma, and value are our color nomenclature. Additional components of the science of color are as follows: how the light carries the color, how an object reflects the color, and how a person perceives the color. The phenomenon of color is perceived differently from one person to another. In fact, when we influence the light, we alter this phenomenon and therefore change our perception of a given color.

Just as dentistry has its own nomenclature, so does color science. Imagine how difficult it would be to describe an area on the disto-facial aspect of tooth No. 14 if you did not understand the term disto-facial. We need to understand the science behind color in order to describe colors using terms that we all can understand. It is a common occurrence in a laboratory prescription to see instructions such as these: make the crown a little lighter, make the crown a bit darker, this crown is too gray, or the crown needs more translucency. These requests are not as descriptive as they need to be in order for the laboratory to return the exact result that the dentist intended.

Here is how Webster’s Dictionary defines color: “A phenomenon of light or visual perception that enables one to differentiate otherwise identical objects.” In other words, light is color and color is light. Color travels as light waves that are part of the electromagnetic spectrum. We can define color by measuring its specific wavelength and therefore quantify these waves into their respective colors. This is defined as the hue: the specific wavelength of light within the electromagnetic spectrum. As an example, halogen curing lights emit a blue light in the 440-nm range.

If individual colors have specific wavelengths, how do we differentiate highly saturated colors from one another? How can we distinguish between royal blue versus sky blue? Chroma distinguishes highly saturated colors from less saturated colors.

The human eye is most sensitive to differences in lightness or darkness of a given object. We have approximately 20 times the number of “perceptors” in the retina to determine black and white versus the number of “perceptors” to see color. Value is the lightness or darkness in shades of gray. Light objects have a high value and dark objects have a low value. If a shade is wrong it is almost always an incorrect value.

Light carries color to and from an object and eventually to our eye. Color is light and light is color. If the light quality is poor, our perception of the actual color will be poor. It is similar to brewing expensive coffee with poor quality tap water. The water carries the flavor of the coffee just as the light carries the color we perceive. In the dental operatory, fluorescent bulbs that are not color corrected will give off a red spectrum and will result in incorrect perception of the shade. The best light sources are natural daylight or light sources that are color corrected.

Light quantity is also important. Too much or not enough light can influence how we perceive colors. The quantity of light is measured in foot-candles and should be in the range of 150 to 200. Anything in the operatory that alters the transmission quality or quantity will alter our perception of any color.

Objects reflect color. Most of the light we perceive is reflected (not direct) light. The color of the light we perceive is that portion of the visible spectrum that is not absorbed by the object. When you look at an object that appears red, the object is actually absorbing all the colors except red. White is actually the reflection of all the colors contained in visible light. Black is the absorption of all the colors contained within visible light.

The eye perceives color, and the brain processes the light images that are received and allows for the perception of color. The brain can be fooled into seeing colors differently. Staring at a tooth for more than 5 seconds will cause you to perceive the color incorrectly, because your eye becomes accommodated to the colors red and yellow. This is the reason why we recommend staring at a blue object between looking at shade tabs. It allows the retinal memory to be recalibrated. This action is similar to smelling coffee beans when you buy perfume. Smelling the beans between smelling each perfume recalibrates your sense of smell, just like the blue object recalibrates your eye between shades. It is imperative to verify the shade you selected with another person. This will help to ensure that the shade chosen is correct for that patient.

UNDERSTANDING WHAT INFLUENCES OUR PERCEPTION OF COLOR

Transmission of Light

Altering the transmission of light can affect our perception of color. Anything that alters light transmission will affect our ability to choose shades correctly. Framing the dentition with lipstick or a rubber dam, or choosing the shade when the surrounding gingiva is red and swollen can affect our perception of color. Poor quality lighting or light that is transmitted through a dusty cover or diffuser can affect our perception of color. Bright-colored clothing or a brightly colored operatory will also affect light transmission and therefore affect selection of the correct shade.

The Object

Our perception of color can be influenced by the object being observed. The composition of the object itself—the texture and/or staining of the object’s surface—can alter our perception of color. Extrinsic stain from tobacco or dark liquids such as coffee or red wine can alter our perception. Intrinsic stain from caries, dark dentin secondary to pulpal necrosis, or darkened dentin from an amalgam restoration can alter our perception. Desiccated tooth structure can cause the value to appear higher, whereas a rough surface can cause the value to appear lower.

Differences Between One Person and Another Will Alter Our Perception

We are not all created equal when it comes to our ability to perceive colors: some individuals have a difficult time differentiating between shades that are close together on the shade guide. Certain medications can alter our ability to differentiate between shades by altering our ability to see certain colors clearly. Even our emotions can change our color perception by altering the amount of light entering the eye though the pupils.

UNDERSTANDING PREDICTABLE SHADE-TAKING

|

Table. Appropriate Time to Take a Shade. |

||||||||||||||

|

Knowing when to select the shade is as important as knowing how to take a shade. Taking the shade at an inappropriate time can influence the shade of the restoration; a list of examples is provided in the Table.

Step-by-step shade-taking starts with an appropriate shade guide. Make sure you are using a shade guide that is appropriate for the material to be used; ie, do not use a denture shade guide to select a shade for porcelain. Place the shade tabs in value order to make your selection easier. The instructions to reorder the tabs come with the shade guide.

1. The chair light should be turned off.

2. If necessary, the patient should be placed in an area that has natural light or light that is color corrected.

Bringing the entire shade guide to the patient’s mouth, a shade tab that matches should be quickly selected.

1. Your first selection is the one to trust.

2. Don’t stare at the tabs; glance at them from the corner of your eye.

3. Hold the tab next to the tooth being matched:

• To determine value, match incisal edge to incisal edge.

• To determine the hue, match the middle one third to the middle one third.

4. If your initial selection does not match, then select a new tab.

5. A new selection should be based on value and/or hue.

6. Between tabs, always look at the blue paper for 10 seconds.

7. Obtain at least 2 opinions on the selected shade.

MEETING THE REDUCTION REQUIREMENTS FOR THE SELECTED MATERIAL

Consideration of the material that will be used for the restoration is in many ways the most important piece of this puzzle. The most accurately chosen shade by the most capable operator cannot be reproduced by the laboratory without sufficient reduction for the chosen material. Laboratory-fabricated materials have reduction requirements for both structural integrity and shade control.

Although some materials are translucent and are made to mimic the enamel they replace, others have substructures that are opaque. The latter can be used to mask discolored dentin or metal posts, or provide opacity for a significant shade shift. If the amount of reduction accomplished for these materials with an opaque substructure is not sufficient, the restoration will appear dull, lifeless, and opaque.

Having a good working relationship with your laboratory is crucial to reduce problems with the fourth piece of this puzzle. Lines of communication between the dentist and the laboratory should be open. The laboratory needs to be a member of your total dental healthcare team. If the technician feels you will not receive the result that you and your patient expect from the preparations provided, he or she should communicate this to you. A different material might be selected, or the dentist may choose to reprepare the teeth to achieve the desired result.

CONCLUSION

With a better understanding of the 4 pieces of the shade selection puzzle you will be well on your way toward success in shade communication. Knowledge of color science and peripheral influences, combined with effective and detailed communication, will contribute to greater predictability in shade selection. Including your laboratory technician as a member of your total dental healthcare team can help reduce shade selection problems and increase your predictable success.

Sources

Al-Wahadni A, Ajlouni R, Al-Omari Q, et al. Shade-match perception of porcelain-fused-to-metal restorations: a comparison between dentist and patient. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:1220-1225.

Chu SJ, Devigus A, Mieleszko AJ. Fundamentals of Color: Shade Matching and Communication in Esthetic Dentistry. Chicago, Ill: Quintessence Publishing Co; 2004:2-9, 14-16.

Mendelson MR. Effective shade taking: a step-by-step guide for accuracy. Contemporary Dental Assisting. September 2006. Available at: http://www.contemporarydentalassisting.com/article.php?s=CDA/2006/09&p=3. Accessed September 25, 2006.

Shulman JD, Maupome G, Clark DC, et al. Perceptions of desirable tooth color among parents, dentists and children. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:595-604.

Ubassy G. Shape and Color: The Key to Successful Ceramic Restorations. Chicago, Ill: Quintessence Publishing Co; 1993:17-23.

Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Available at: http:www.m-w.com. Accessed September 2006.

Dr. Mendelson is the director of education for Americus Dental Labs. He primarily functions as the clinical liaison between the dentist and the laboratory. Dr. Mendelson lectures nationally and is an adjunct clinical faculty member of Nova Southeastern University. He is a member of the Florida Dental Association, National Speaker’s Association, and OSAP’s Speaker Bureau. Dr. Mendelson can be reached at martinm@americus-clearwater.com.