Over the past two decades, the evolution of adhesive techniques has transformed the scope of dental practice. In North America, the majority of direct and indirect restorations are bonded to natural tooth structure rather than cemented or mechanically retained. Extensive research and product development have consistently improved the adhesive armamentarium available to the dentist, broadening its applications and range. Patient interests and demands have reflected a newfound interest in oral appearance and health, most commonly associated with adhesive procedures.

THE GENERATIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF ADHESIVE SYSTEMS

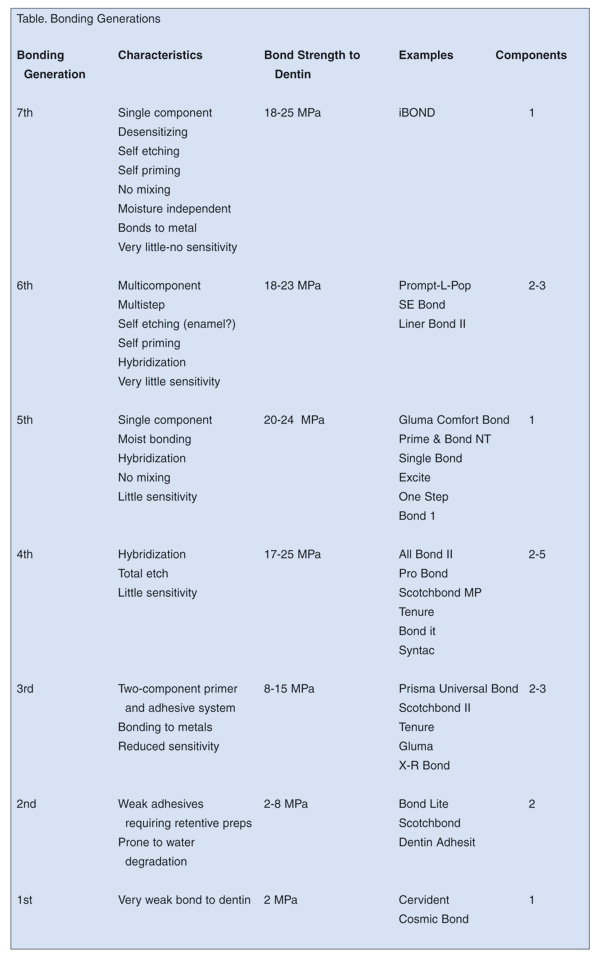

The first generation adhesives in the late 1970s were really nothing of the sort. While their bond strength to enamel was high (generally, all the generations of adhesives bond well to the microcrystalline structure of enamel; it is their bond strength to the semi-organic dentin that is the major problem facing dentists), their adhesion to dentin was pitifully low, typically no higher than 2 MPa. Bonding was achieved through chelation of the bonding agent to the calcium component of the dentin. While tubular penetration did occur, it contributed little to the retention of the restoration. It was common to see debonding at the dentinal interface within several months.1 These bonding agents were recommended primarily for small, retentive class III and class V cavities.2 Postoperative sensitivity was common when these bonding agents were used for posterior occlusal restorations.3

the fourth-generation adhe-sives.19-22 The materials in this group are distinguished by their components; there are two or more ingredients that must be mixed, preferably in precise ratios. This is easy enough to accomplish in the research laboratory, but rather more complicated chairside. The number of mixing steps involved and the requirement for exact component measurements tend to confuse the process and reduce the bonding strengths to dentin.

SEVENTH-GENERATION ADHESIVE TECHNIQUE

The following is an abbreviated technique description for the use of seventh-generation adhesives:

|

|

|

Figure 1. Distal surface decay. |

Figure 2. Decay removed. |

|

|

| Figure 3. Conservative preparation. | Figure 4. Preparation is bonded, |

|

|

|

Figure 5. Bonding agent is light cured. |

Figure 6. Cavity is restored and interproximal contact is made. |

|

|

|

Figure 7. The occlusal surface is preshaped. |

Figure 8. Rough and intermediate polishing. |

|

|

| Figure 9. Final surface polishing. | Figure 10. The completed restoration. |

(1) Decay is noted on the distal surface of the right mandibular second bicuspid (Figure 1).

(2) The decay is accessed and removed with the Great White No. 2 bur (SS White) (Figure 2).

(3) The conservative cavity preparation is complete. The tooth is matrixed (OmniMatrix, Ultradent) and wedged (Flexi Wedge, Garrison Dental) (Figure 3).

(4) The preparation is bonded with iBOND (Heraeus Kulzer) (Figure 4).

(5) The bonding agent is light cured (Figure 5).

(6) The cavity is restored with Venus (Heraeus Kulzer), and the interproximal contact is made with the CCI (Contact Curing Instrument, Hu-Friedy) (Figure 6).

(7) The occlusal surface is preshaped prior to curing of the surface layer with the “Duckhead” instrument (Hu-Friedy) (Figure 7).

(8) Rough and intermediate polishing are done with the Posterior Composite Finishing Kit (Brasseler USA). The instrument shown is the VisiFlex disk for marginal ridges and embrasures (Figure 8).

(9) Final surface polishing is accomplished with the POGO polisher (DENTSPLY Caulk) (Figure 9).

(10) The completed restoration (Figure 10).

CHEMISTRY OF DENTIN BONDING AGENTS

While the currently available dentin bonding agents effectively join composites to the surface of dentin, they can be improved. When manipulated under carefully controlled conditions, the clinical longevity of the bonded resin is as good as any other material used by the restorative dentist. Unfortunately, some of these systems have been found to be somewhat more technique sensitive than originally supposed. In a study with fourth-generation dental adhesives (which may possibly apply to fifth-generation products as well), Hashimoto has demonstrated that gradual debonding from the dentinal surface can occur over a period of time.23 The bond strength of posterior composite resin restorations adhered with fourth-generation materials decreased by nearly 75% aging over a 3-year period. In addition, scanning electron microscopy demonstrated that some of the collagen fibers beneath the hybrid zone had undergone levels of degradation. While this study was conducted on primary posterior teeth, the same conclusion could be extended to restored permanent teeth. This rationale is based on the fact that the mechanism of bonding to collagen, and the formation of the hybridized zone, are similar for both types of dentition.21

Obviously, there are other factors that may influence this level of penetration. Overdrying the preparation, and thus the failure to leave some residual water on the surface (moist bonding), may discourage the primer from penetrating the dentin. Excess water on the surface may also prevent the influxing of the bonding agent. Another potential source for inadequate diffusion may be related to the premature vaporization of the alcohol or acetone solvent within the bonding agent.

CONCLUSION

The inherent advantage of the self-etching dentin bonding agents is that they etch and deposit the primer simultaneously. With this procedural sequence, it is likely that the underfilling of the inorganic depleted zones will not occur. Consequently, the possibility of both long-term bond strength reduction and postoperative sensitivity are diminished considerably. Furthermore, technique sensitivity is reduced, as are the number of steps normally required for bonding composites to the dentin surface. The latest “generation” adhesive makes bonded dental procedures easier, better, and more predictable.

References

- Harris RK, Phillips RW, Swartz ML. An evaluation of two resin systems for restoration of abraded areas. J Prosthet Dent. 1974;31:537-546.

- Albers HF. Dentin-resin bonding. Adept Report. 1990;1:33-34.

- Munksgaard EC, Asmussen E. Dentin-polymer bond promoted by Gluma and various resins. J Dent Res. 1985;64:1409-1411.

- Causlon BE, Improved bonding of composite resin to dentin. Br Dent J. 1984;156:93.

- Joynt RB, Davis, EL Weiczkowski G, Yu XY. Dentin bonding agents and the smear layer. Oper Dent. 1991;16:186-191.

- Lambrechts P, Braem M, Vanherle G. Evaluation of clinical performance for posterior composite resins and dentin adhesives. Oper Dent. 1987;12:53-78.

- Christensen GJ. Bonding ceramic or metal crowns with resin cement. Clin Res Assoc Newsletter. 1992;16:1-2.

- O’Keefe K, Powers JM. Light-cured resin cements for cementation of esthetic restorations. J Esthet Dent. 1990;2:129-131.

- Barkmeier WW, Latta MA. Bond strength of Dicor using adhesive systems and resin cement. J Dent Res. 1991;70(Abstract):525.

- Holtan JR, Nyatrom GP, Renasch SE, Phelps RA, Douglas WH. Microleakage of five dentinal adhesives. Oper Dent. 1993;19:189-193.

- Fortin D, PerdigaoJ, Swift EJ. Microleakage of three new dentin adhesives. Am J Dent. 1994;7:217-219.

- Linden JJ, Swift EJ. Microleakage of two dentin adhesives. Am J Dent. 1994;7:31-34.

- Barkmeier WW, Erickson RL. Shear bond strength of composite to enamel and dentin using Scotchbond multi-purpose. Am J Dent. 1994;7:175-179.

- Bouvier D, Duprez JP, Nguyen D. Lissac M. An in vitro study of two adhesive systems: third and fourth generations. Dent Mater. 1993;9:355-369.

- Gwinnett AJ. Shear bond strength, microleakage and gap formation with fourth generation dentin bonding agents. Am J Dent. 1994;7:312-314.

- Swift EJ, Triolo PT. Bond strengths of Scotchbond multi-purpose to moist dentin and enamel. Am J Dent. 1992;5:318-320.

- Fusayama A, Kohno A. Marginal closure of composite restorations with the gingival wall in cementum/dentin. J Prosthet Dent. 1989;61(3):293-296.

- Nakabayashi N. Bonding mechanism of resins and the tooth. Kokubyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1982;49(2):410.

- Kanca J. Effect of resin primer solvents and surface wetness on resin composite bond strength to dentin. Am J Dent. 1992;5:213-215.

- Kanca J. Resin bonding to wet substrate. I. Bonding to dentin. Quintessence Int. 1992;23:39-41.

- Gwinnett AJ. Moist versus dry dentin; its effect on shear bond strength. Am J Dent. 1992;5:127-129.

- Pashley DH. The effects of acid etching on the pulpodentin complex. Oper Dent. 1992;17:229-242.

- Hashimoto M, Ohno H, Kaga M, et al. In vivo degradation of resin-dentin bonds in humans over 1 to 3 years. J Dent Res. 2000; 79:1385-1391.

Dr. Freedman is a past president of the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry and currently associate director of the Esthetic Dental Education Center at the State University of New York at Buffalo. He is also director of postgraduate programs in aesthetic dentistry at the University of Florida, University of California at San Francisco, University of Missouri (Kansas City), Eastman Dental Center (Rochester), university programs in Seoul, South Korea, London England, and Schaan, Liechtenstein, and Scientific Chairman of the World Aesthetic Congress (London, England). Dr. Freedman is the author of 7 textbooks, more than 170 dental articles, and numerous CDs, and video and audiotapes. A diplomate of the American Board of Aesthetic Dentistry, he lectures internationally on dental aesthetics, dental technology, and photography. Dr. Freedman maintains a private practice limited to aesthetic dentistry in Toronto, Canada, and can be reached at (905) 513-9191.

Dr. Leinfelder is professor emeritus, University of Alabama and adjunct professor, University of North Carolina. He is the recipient of the Dr. George Hollenbeck Award (1995) as well as the Norton N. Ross Award for outstanding clinical research (1997), and the American College of Prosthodontists Distinguished Lecturer Award (1998). He has served as associate editor of the Journal of the American Dental Association and as a dental materials research consultant for numerous materials companies. Dr. Leinfelder has been published extensively and lectures nationally and internationally on clinical biomaterials.