Prions, only truly understood by the scientific and medical community in the past 2 decades, are abnormal proteins that behave in a manner that is different from other proteins. Normal proteins are not organisms and historically are not implicated in disease transmission. In fact, proteins were never believed to be capable of causing disease. It appears that prions convert normal proteins in the cells into prions like themselves.

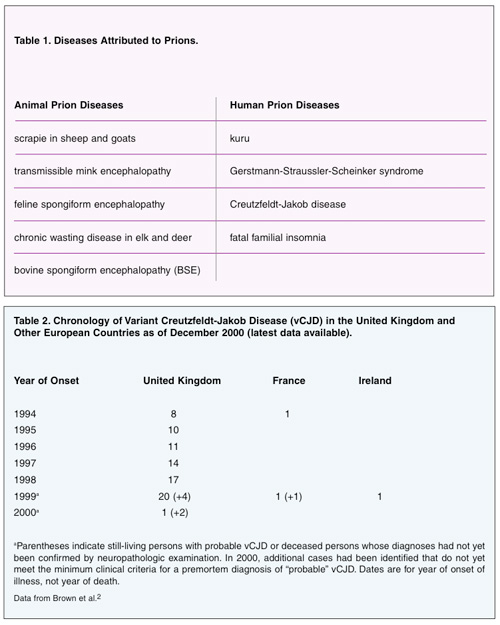

The groups of diseases caused by prions are termed transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE).1 The prions enter brain cells and convert PrPC, the normal cell protein, to the prion form called PrPSC. The prion-bloated brain cells die and release more prions into the brain, in turn infecting additional brain cells. Eventually, the PrPSC proteins become numerous enough to clog the infected brain cells completely. Groups of destroyed brain cells give the brain the sponge-like appearance alluded to in the name of the disease when viewed microscopically postmortem. The brain cells misfire, work poorly, or do not work at all. This results in the infected individual or animal exhibiting dementia, uncoordinated movements, or inappropriate and unusual behavior. TSE is a progressive and fatal group of diseases found in humans and animals (Table 1).

BACKGROUND

In humans, TSE may present as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). Three known transmission methods exist for this disease: sporadic, familial, and acquired. In sporadic CJD, the disease appears even though the person has no known risk factors for the disease. This is by far the most common type of CJD and accounts for at least 85% of cases.

In hereditary CJD, the person has a family history of the disease and/or tests positive for a genetic mutation associated with CJD. About 5% to 10% of cases of CJD in the United States are hereditary.

Transmission of acquired CJD is by exposure to brain or nervous system tissue, usually during certain medical procedures (iatrogenic). There is no evidence that CJD is contagious through casual contact with a CJD patient. Since 1920, less than 1% of cases have been acquired CJD.

|

Mad Cow Disease and CJD

In 1986, prions were introduced to the public when an outbreak of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), commonly called “mad cow disease,” occurred in Great Britain. Cows became mysteriously ill with a disease that caused them to wobble, stagger, and appear fearful. Ultimately the cows died, and it was determined that they were suffering from BSE.

Alarmingly, approximately a decade later, 10 people in Great Britain developed Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease that did not present in the classical manner previously observed in humans. Sporadic cases of CJD had been observed for many years, with a worldwide death rate of approximately one case per million people per year. It is mostly observed in people age 55 to 75 years old. The cases in Great Britain were in young adults, all of whom had consumed beef from cows infected with BSE. These cases were termed variant CJD (vCJD) because they were not the sporadic, familial, or iatrogenic cases that had been believed to be the only forms of the disease. It is believed the infection spread to the cattle from feed derived from sheep infected with scrapie. During the slaughtering of cows and processing of beef, it is possible to contaminate the beef with brain material or other central nervous system (CNS) material that harbors prions. To date, public health authorities have identified 143 people in Great Britain and 10 elsewhere as suffering from vCJD related to BSE-infected meat (Table 2).2

|

INFECTION CONTROL CONSIDERATIONS

Iatrogenic transmission of CJD has been reported in more than 250 patients worldwide. These cases have been linked to the use of contaminated human growth hormone, dura mater, corneal grafts, or neurosurgical equipment. Of the 6 cases linked to the use of contaminated equipment, 4 were associated with neurosurgical instruments and 2 with stereotactic EEG depth electrodes.3 All of these equipment-related cases occurred before the routine implementation of sterilization procedures currently used in healthcare facilities. Such cases have not been reported since 1976, and no iatrogenic CJD cases associated with exposure to the CJD agent from surfaces such as floors, walls, or countertops have been identified.

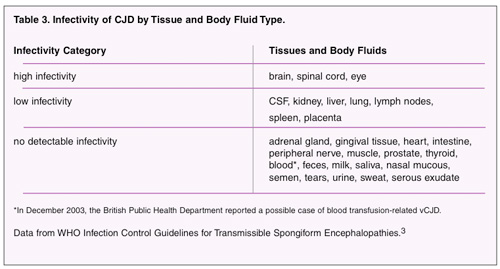

In determining the need for special infection control measures, it is important to understand that the likelihood of transmission is related to the type of medical treatment being rendered and what human tissues or body fluids contaminate the instruments (Table 3). There is no evidence to suggest that dental instruments and procedures carry a risk for iatrogenic transmission of CJD. The strongest evidence for a low or negligible risk comes from an Australian case-control study reported in Lancet.4 This study found no association between the development of sporadic CJD among 241 cases with having major dental work, defined as treatment beyond fillings and dental hygiene such as root canals and tooth extractions.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued new infection control guidelines for dentistry in December 2003. In the guidelines, the issue of infectivity of oral tissues for CJD remains an unresolved issue. The guidelines state: “…CJD was not associated with dental procedures (eg, root canals or extractions), with convincing evidence of prion detection in blood, saliva, or oral tissues, or with DHCP becoming occupationally infected with CJD.”5 The guidelines offer no recommendations due to the lack of evidence for precautions beyond standard precautions.

The transmissions of CJD that have occurred in healthcare settings are associated with exposure to infected central nervous tissue (eg, brain and dura mater), pituitary tissue, or eye tissue. Although the CDC makes no recommendations for special precautions in dentistry, it offers for consideration the following list of precautions in the guidelines:

- “Use single-use disposable items and equipment whenever possible.

- Consider items difficult to clean (eg, endodontic files, broaches, and carbide and diamond burs) as single-use disposables and discard after one use.

- To minimize drying of tissues and body fluids on a device, keep the instrument moist until cleaned and decontaminated.

- Clean instruments thoroughly and steam-autoclave at 134°C for 18 minutes. This is the least stringent of sterilization methods offered by the World Health Organization. The complete list is available at who.int/emc-documents/tse/

whocdscraph2003c.html. - Do not use flash sterilization for processing instruments or devices.”

The relative rarity of CJD and absence of vCJD in the United States indicates this fatal disease does not present a high risk of patient-to-patient or patient-to-healthcare worker transmission in the dental setting. (One person in the United States was identified postmortem of having suffered from vCJD. However, that individual had lived in Britain during the time infected beef was consumed.) As the science progresses and new infection control guidelines emerge, it will be important for dental workers to ensure they understand the transmission of all emerging diseases.

References

- Belay ED. Prions and prion diseases: current perspectives [book review]. Emerg Infect Dis. [serial online] Dec 2004. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol10no12/04-0847.htm. Accessed February 18, 2005.

- Brown P, Will RG, Bradley R, et al. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy and variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: background, evolution, and current concerns. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:6-16.Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol7no1/brownG.htm. Accesed on Feb 28, 2005.

- World Health Organization. WHO Infection Control Guidelines for Transmissible Spongiform Enceph-alopathies. Report of a WHO Consultation; Geneva, Switzerland; 23-26 March 1999. Communicable Disease Surveillance & Response Web site. Available at: http://www.who.int/emc-documents/tse/whocdscsraph2003c.html. Accessed February 24, 2005.

- Collins S, Law MG, Fletcher A, et al. Surgical treatment and risk of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: a case-control study. Lancet. 1999;353:693-697.

- Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, et al. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings – 2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(No. RR-17):1-61.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Dr. Jennifer Cleveland of the CDC division of oral health for her expertise and assistance with this article.

Ms. Cuny is the director of environmental health and safety and assistant professor in the department of pathology and medicine at the University of the Pacific School of Dentistry. She is past chairman of the Organization for Safety and Asepsis Procedures (OSAP). She can be reached at ecuny@pacific.edu.