Visualizing the oral cavity has always posed a challenge in dentistry. From early fiber optic lights mounted on handpieces to today’s sophisticated procedure scopes, visualization solutions have recently evolved at an unprecedented rate. Modern magnification aids are raising dentists’ productivity, and the level of excellence and confidence in dental treatment.1 However, the ergonomic advantages of magnification are increasingly being recognized as an important reason to invest in them. Students have been found to work in an ergonomically better posture while using magnification lenses when compared to using regular safety glasses.2

But what are the ergonomic implications of improved posture? Consider that working with a forward head posture of only 20° or more for 70% of the working time has been associated with neck pain.3 Most dentists and hygienists operate with a forward head posture of at least 30° for 85% of their time in the operatory.4 It should come as no surprise that the prevalence of neck pain among dentists hovers around 70%.5,6

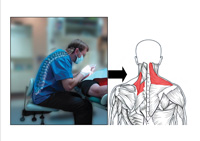

When operating without magnification aid, the head and neck tend to be held in an unbalanced forward position. In this posture, the vertebrae cannot properly support the spine, causing shoulder stabilizing muscles to fatigue quickly.7 Other muscles (the upper trapezius, levator, and upper rhomboid muscles) must then compensate to stabilize the neck and shoulder. This makes these muscles perform a job for which they were not designed, and they become tight, ischemic, and painful8 (Figure 1). This can result in a common pain pattern among dental professionals known as tension neck syndrome (TNS). TNS sufferers have headaches and chronic pain in the neck, shoulders, and interscapular muscles that can radiate pain into the arms. Cervical disc degeneration or spondylosis can also result from excessive forward head posture.9

Properly designed magnification systems can enhance operator working posture by maintaining a set focal range (as with loupes) or by location of fixed binoculars (microscope) or an LCD screen (procedure scopes). Depending on the type, magnification supports the operator in head postures ranging from about 0° to 25° forward. However, it is important to note that improper adjustment or selection of these magnification aids can worsen existing pain syndromes or increase the risk of injury.

MAGNIFICATION TYPES

Magnification designs have come a long way in the last decade. Lighter loupe designs with better declination angles have made believers out of many operators who previously purchased loupes, only to abandon them in frustration. As with any ergonomic product, magnification requires proper selection, adjustment, accommodation time, and usage to realize its benefits.

There are 3 basic types of magnification on the market today: the procedure scopes, surgical operating microscopes, and loupes (or telescopes).

|

|

| Figure 1. Forward head posture is common with unmagnified vision, which can lead to a pattern of painful muscle imbalances (Posturedontics, 2008). | Figure 2. The procedure scope is the newest magnification aid and allows the operator to sit upright while viewing images on an LCD screen (MagnaVu procedure scope shown [Posturedontics, 2008]). |

|

|

Figure 3. A microscope fitted with an ergonomic adapter (circled) enables a near-neutral head posture. (Global Surgical Microscope with Carr Binocular Extender shown, courtesy of Dr. Donato Napoletano.) |

Loupes

Loupes, also referred to as telescopes, are the most popular type of magnification used in dentistry today. While none of these loupe systems provide neutral head posture (ear-over-shoulder), well-designed telescopes may significantly improve operator working postures in dentistry that contribute to musculoskeletal disorders2 and contribute to clinician comfort.1

Well-designed loupes should enable a working posture of less than 25° of forward head posture.11 Loupes range in strength from about 2x to 5x and are available in 2 basic styles: front lens mount (flip-ups) and fixed mounts, also called through- the-lens (TTL).

TTL loupes have the scope mounted directly into the carrier lens with a fixed declination angle. Since they are fixed, the loupes do not get knocked out of alignment. Compared to flip-up loupes, they are lighter and offer a wider field of vision, since the scope is closer to the eyes. Prescription lenses can be included in the carrier lens

of the fixed loupes to enable distance viewing. However, if the prescription changes, the loupes must then be modified by the manufacturer.

Flip-up loupes have the scope mounted on a hinge mechanism in front of the carrier lens and can be flipped-up during a procedure. Advantages, compared to fixed loupes, include a better declination angle for head posture and the ability to easily have eyeglass prescriptions changed by the clinician’s optician. On the other hand, flip-up loupes are sometimes heavier than fixed loupes and can also be knocked out of alignment.

ERGONOMIC CRITERIA FOR SCOPE SELECTION

Since poorly designed, or poorly adjusted loupes can cause or worsen pain syndromes, it is imperative that ergonomic guidelines are considered when selecting loupes. The 3 most important ergonomic factors to consider when purchasing loupes are: declination angle, working distance, and frame size/shape.

|

|

| Figure 4. Loupes with a good declination angle (red lines) will allow the operator to work with minimal forward head posture. (Surgitel flip-up loupes shown [Posturedontics, 2008].) | Figure 5. A ratcheting hinge mechanism on the frame of a TTL loupe allows for significantly improved declination angle. (Designs for Vision loupes shown, courtesy of Dr. Kathleen Adams, OHSU School of Dentistry.) |

Since glasses rest differently on each operator’s face, the same pair of loupes may have a slightly different declination angle from one person to the next. The declination angle (and resultant forward head posture) that various manufacturers offer varies dramatically (Table), and can either benefit or worsen your musculoskeletal health. Generally, flip-up style loupes allow for a steeper declination angle and more neutral head posture compared to TTL loupes. However, some manufacturers now offer a TTL loupe with a ratcheting mechanism on the frame that significantly improves the declination angle (Figure 5). When ordering TTL loupes, it is generally a good idea to request the steepest declination angle possible.

| Table. Comparison of Magnification Aids | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

* Best working postures measured by the author during in-office dental ergonomics consultations, representing various manufacturers’ magnification systems. |

Working Distance

The working distance is defined as the distance from the eyes to the working area. If the working distance is measured too short, it can result in excessive neck flexion or hunching.14 If possible, measure the working distance in your own operatory, with a patient in the chair. Sit in neutral operating position, with patient’s mouth at or 4 cm above elbow level. Have someone view you from the side and measure the distance from your eye to the work surface, or tooth. Working distances will vary for shorter operators (14 inches or less) to extra long working distances for very tall operators (more than 20 inches). Therefore, working distance should be tailored to the individual.

|

| Figure 6. Large frames that sit low on the cheek allow lower positioning of scopes, leading to better head posture. (Orascoptic TTL loupes shown with Rudy Sports frame, courtesy of OHSU School of Dentistry student, Erich Ott [Posturedontics, 2008]. ) |

SELECTING TELESCOPES

General guidelines for magnification strength are as follows: for hygienists, 2x to 2.5x; for general dentists, 2.5x to 3.5x; for endodontists/periodontists, 3.5× to 4.5× or higher. In general, operators should start with the lowest magnification at which they can view and control the surgical field. Keep in mind that higher-powered scopes will create a shorter depth of field, which may make working in multiple areas of the mouth difficult.

Illumination

Inadequate lighting can also lead to contorted postures to view shadowed areas of the mouth. To prevent shadowing, Dr. Lance Rucker, ergonomic expert and director of clinical simulation at University of British Columbia, advises positioning the operatory light parallel to, or within 15° of, the operator’s line of sight.15 This will usually require the operatory light to be located slightly behind the operator’s head, which may be difficult due to fixed ceiling track mounts.

Procedure and microscopes provide direct (parallel) lighting to the operator’s line of sight. Use of a headlight mounted to loupes will also closely parallel the operator’s line of sight. This can significantly reduce shadowing by aligning the direction of the light with your own sight line.

When properly utilized, magnification can significantly improve posture and therefore help prevent numerous musculoskeletal disorders to which dentists are prone. However, prolonged, static postures and weak postural muscles can still contribute to pain syndromes and MSD.16 By combining ergonomic magnification with chairside stretching, positioning techniques and postural strengthening, the multifactorial problem of work-related pain in dentistry can most effectively be addressed.

References

- Spear FM. One clinician’s journey through the use of magnification in dentistry. Advanced Esthetics and Interdisciplinary Dentistry. 2006; 2:30-32.

- Branson BG, Bray KK, Gadbury-Amyot C, et al. Effect of magnification lenses on student operator posture. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:384-389.

- Ariens GA, Bongers PM, Douwes M, et al. Are neck flexion, neck rotation, and sitting at work risk factors for neck pain? Results of a prospective cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2001; 58:200-207.

- Marklin RW, Cherney K. Working postures of dentists and dental hygienists. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2005; 33:133-136.

- Lehto TU, Helenius HY, Alaranta HT. Musculoskeletal symptoms of dentists assessed by a multidisciplinary approach. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1991;19:38-44.

- Rundcrantz BL, Johnsson B, Moritz U. Cervical pain and discomfort among dentists. Epidemiological, clinical and therapeutic aspects. Part 1. A survey of pain and discomfort. Swed Dent J. 1990;14:71-80.

- Hertling D, Kessler RM. Management of Common Musculoskeletal Disorders: Physical Therapy Principles and Methods. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1996: 551-552.

- Novak CB, Mackinnon SE. Repetitive use and static postures: a source of nerve compression and pain. J Hand Ther. 1997; 10:151-159.

- Katevuo K, Aitasalo K, Lehtinen R, et al. Skeletal changes in dentists and farmers in Finland. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1985; 13:23-25.

- Cuomo GM. Posture-directed vs. image-directed dentistry: ergonomic and economic advantages through dental microscope use. http://www. heryschein.com/usen/dental/services/cehp/HomeStudy.aspx. Published April 27, 2006. Accessed November 14, 2008.

- Chang BJ. Ergonomic benefits of surgical telescope systems: selection guidelines. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2002;30:161-169.

- Cailliet R. Neck and Arm Pain. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis; 1991:74-75.

- Rucker LM, Beattie C, McGregor C, et al. Declination angle and its role in selecting surgical telescopes. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999; 130:1096-1100.

- Valachi B. Vision quest: finding your best working distance when using loupes. Dental Practice Report. 2006;4:49-50.

- Murphy DC, ed. Ergonomics and the Dental Care Worker. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 1998: 246-249, 310-311.

- Valachi B, Valachi K. Mechanisms leading to musculoskeletal disorders in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1344-1350.

Ms. Valachi is a physical therapist, dental ergonomic consultant and CEO of Posturedontics, a company that provides research-based dental ergonomic education. Also a clinical instructor of ergonomics at OHSU School of Dentistry in Portland, Ore, she lectures internationally at dental meetings, schools, associations, and study clubs. She covers the above topics and much more in her new book, Practice Dentistry Pain-Free: Evidence-based Strategies to Prevent Pain and Extend Your Career, available through the Web site posturedontics.com or by calling (503) 291-5121. She welcomes comments and may be reached via e-mail at bethany@posturedontics.com.

Disclosure: Ms. Valachi is the CEO of Posturedontics and received no compensation for writing this article.