Admission into dental school is a high-stakes, resource-intensive process for dentistry programs and applicants alike. Fortunately, increasing research into how people enter the health professions has created stronger validation evidence for the use of various tools in assessing applicants.1 It then falls upon admissions committees to weigh the quality of this evidence from the perspective of diverse stakeholders and resource utilization.

Most dental school programs historically have utilized a selection model, which includes both measures of academic (cognitive) abilities and non-academic (personal/professional) qualities, across their applicant pool to determine who to admit. Over the past 15 years, though, the traditional measures of selection have been challenged as methodological and technological advances have changed the options available in the way we select applicants and how we use that information to inform the development of the ideal matriculating class.

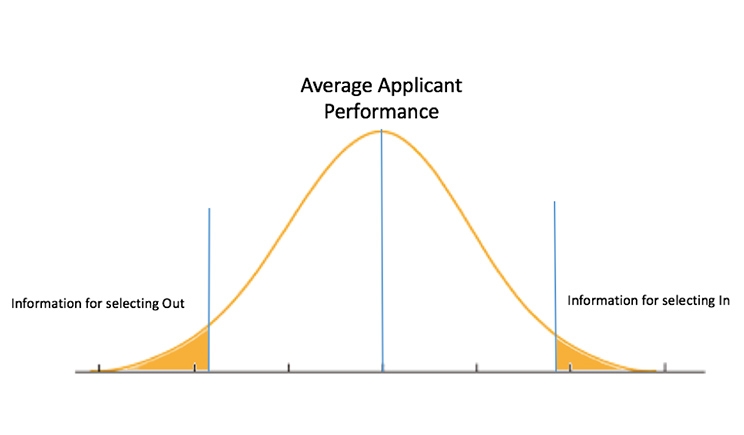

Importantly, before discussing measures of selection, programs must identify the goals of the selection process. Specifically, are they using the information gathered on the applicants to “select-out” or to “select-in” potential students?

In highly competitive applicant pools, like dentistry, information about the lowest-performing applicants—either about their cognitive ability or personal/professional qualities—will guide who gets selected-out. By identifying applicants who are performing at the bottom level of performance compared to their peers (typically 2 standard deviations below the mean), programs can ensure that low-performing students progress no further in the selection process (see the figure).

On the other hand, some selection measures can tease apart performance for applicants in the top end of the bell curve, such as who sits well above their peers in terms of academic or personal/professional qualities. Admission committees in highly competitive programs can use this information to select-in the highest-level applicants to progress through the selection process.

However, no measures of selection should add additional barriers to applicants from underrepresented demographics. Rather, they should minimize these barriers to widen access across selection.2

To this end, the psychometric qualities of various measures of selection should be reviewed based on their evidence of validation in terms of both reliability and predictive validity. Reliability in this frame is the degree to which the measure can be used to consistently differentiate between applicants (selecting-in and selecting-out). Additionally, where evidence exists, the measures of selection should be compared based on the quality of evidence they provide for predicting applicants’ future performance.

The selection measures can be looked at across the 2 most common phases of selection: screening and interviewing. The goal with screening is to utilize the most efficient selection process to identify the best quality of applicants to invite to interview. Therefore, screening plays an important role in evaluating applicants, across academic and non-academic metrics, facilitating better use of the resource-intensive interview process.

Screening

During pre-interview screenings, admissions programs are challenged to manage resources to filter from the large number of applicants to the best applicants, across academic and non-academic measures, and not waste valuable limited interview spots. Screening measures should be applicable across all those who apply to create an equitable selection process to demonstrate their suitability across academic abilities and non-academic qualities.

Traditional measures of cognitive ability, such as the Dental Aptitude Test (DAT) and grade point average (GPA), have acted as hurdles for applicants to ensure minimal cognitive thresholds are achieved across the applicant pool. The DAT in both the United States3 and Canada,4 which includes an additional measure of manual dexterity, is seen as complementary to the interview and provides additional information.5 Specifically, the DAT has demonstrated correlation with the National Board of Dental Examiners exam.6 Overall undergraduate GPA and science GPA have demonstrated correlation with dental school GPA.7,8 Additionally, GPA has demonstrated some correlation with attrition rates.7(p389)

The assessment of non-academic qualities or personal professional characteristics has proven significantly more difficult9 despite their demonstrated linkage to professionalism complaints in the health professions.10,11 Traditional measures including reference letters, personal statements, or CVs have both high resource requirements for institutions and applicants, yet demonstrate little added value in the selection process.9

In the last decade, research has demonstrated the possibility of selecting applicants using situational judgement tests (SJTs). Unlike behavioral descriptors (“tell me about a time when you…”), SJTs place applicants in a scenario that requires them to respond appropriately. Various models have been developed for this type of assessment for screening purposes. For example, an online test accessible to all applicants adds value and may be less resource-intensive for applicants and institutions.

However, to get a clear prediction of non-academic attributes alone, SJTs must not be job specific. Otherwise, the research has demonstrated that the predictive value will be tied to cognitive outcomes, which may already be assessed with other measures.12 In doing so, programs need to be cognizant that this format of SJT will confound the measurement of academic and non-academic qualities. In Canada, some dental programs have moved to adopt an online video-based SJT known as Computer-Based Assessment for Sampling Personal Characteristics (CASPer), while others in Belgium have used a similar tool.

CASPer has demonstrated reliability13 as well as predictive validation with non-academic performance on national licensure examination.14 Additionally, this test has proven to be more equitable across under-represented groups in medicine compared to standardized cognitive tests.15 Unlike closed-ended SJTs, which tend to be right skewed in terms of their distributions,16 the open-ended nature of CASPer allows for a more even distribution so scores can be used to select-in and select-out. Both the DAT and CASPer z-score results (how many standard deviations an element is from the mean) allow comparison of an applicant to all other applicants that year. Schools may use the screening information in various combinations to then determine the limited pool of applicants they will invite to interview.

Interview

Four common models of interview have been demonstrated across dental selection: traditional interviews,5(p.666-667) situational judgement interviews (which include both patterned behavior description interviews and situational interviews),5 multiple mini interviews (MMIs), and paper and pencil SJTs conducted in person at the time of the MMI/interview.16(p.24) Depending on the model adopted by individual institutions, the weight of questions that reflect academic or non-academic qualities may vary. This may influence the outcomes in the program that correlate with the interview process.

The application of interviews (question format, number of items, number of independent interviewers, scoring, and format itself) varies widely from school to school. Any model must be adopted with caution to ensure the format, resources, and outcomes align with the school’s missions and goals within the selection process. However, overall traditional interviews9 and use of closed-format SJTs has demonstrated some limitations in selecting-in top quality candidates (with results being right skewed, or demonstrating a long tail on the positive end of the results).17 Meanwhile, MMIs and situational interviews tend to demonstrate a more Gaussian, or normal, distribution,4 allowing scores to be used to identify the highest-performing candidates.

Across the selection process, resource limitations require schools to decide how they will apply these admission tools. These decisions must be made in light of psychometrics and also to facilitate wider access. Tools must be considered for their combined benefit to inform programs about applicants’ cognitive abilities and their personal-professional qualities. They also must include information about low-performing candidates and enable schools to select-in applicants who perform well above their peers. Information about how people enter the dental profession will continue to grow, and admission programs will be required to ensure the ongoing quality of their selection process.

References

1. Kane M. Certification testing as an illustration of argument-based validation. Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research and Perspectives. 2004;2:135-170.

2. Powis D, Hamilton J, McManus IC. Widening access by changing the criteria for selecting medical students. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2007;23:1235-1245.

3. American Dental Association. Dental Admission Test (DAT) 2017 Program Guide. ada.org. http://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Education%20and%20Careers/Files/dat_examinee_guide.pdf?la=en. Accessed September 25, 2017.

4. Canadian Dental Association. DAT information. cda-adc.ca. https://www.cda-adc.ca/en/becoming/dat/information/. Accessed September 25, 2017.

5. Poole A, Catano VM, Cunningham DP. Predicting performance in Canadian dental schools: the new CDA structured interview, a new personality assessment, and the DAT. J Dent Educ. 2007;71:664-676.

6. De Ball S, Sullivan K, Horine J, et al. The relationship of performance on the dental admission test and performance on part I of the National Board Dental Examinations. J Dent Educ. 2002;66:478-484.

7. Sandow PL, Jones AC, Peek CW, et al. Correlation of admission criteria with dental school performance and attrition. J Dent Educ. 2002;66:385-392.

8. Curtis DA, Lind SL, Plesh O, et al. Correlation of admissions criteria with academic performance in dental students. J Dent Educ. 2007;71:1314-1321.

9. Salvatori P. Reliability and validity of admissions tools used to select students for the health professions. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2001;6:159-175.

10. Papadakis MA, Teherani A, Banach MA, et al. Disciplinary action by medical boards and prior behavior in medical school. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2673-2682.

11. Papadakis MA, Arnold GK, Blank LL, et al. Performance during internal medicine residency training and subsequent disciplinary action by state licensing boards. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:869-876.

12. Buyse T, Lievens F. Situational judgment tests as a new tool for dental student selection. J Dent Educ. 2011;75:743-749

13. Dore KL, Reiter HI, Eva KW, et al. Extending the interview to all medical school candidates—Computer-based Multiple Sample Evaluation of Noncognitive Skills (CMSENS). Acad Med. 2009;84(suppl 10):S9-S12

14. Dore KL, Reiter HI, Kreuger S, et al. CASPer, an online pre-interview screen for personal/professional characteristics: prediction of national licensure scores. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2017;22:327-336.

15. Juster F, Baum R, Reiter HI, et al. Can situational judgment tests promote diversity? Acad Med. In press.

16. Patterson F, Ashworth V, Mehra S, et al. Could situational judgement tests be used for selection into dental foundation training? Br Dent J. 2012;213:23-26.

17. Rowett E, Patterson F, Cousans F, et al. Using a situational judgement test for selection into dental core training: a preliminary analysis. Br Dent J. 2017;222:715-719.

Dr. Dore is a scientist with McMaster Education Research, Innovation and Theory (MERIT) and an associate in the Departments of . She also holds an affiliated appointment with the Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact. And, she is the Director of the Masters Science in Health Science Education Program. Her current interests include assessment/evaluation, measures of admission (including personal and professional characteristics), the process of transfer of accountability (clinical handover), and the psychological factors relevant to health professions education and clinical decision making. She completed her PhD in health research methodology with a focus on health professions education research and cognitive psychology. She has held multiple grants from both the Medical Council of Canada and the National Board of Medical Examiners (Stemmler Grant).

Related Articles

National Project to Evaluate the State of Dental Education

Trends Evolve in Dental School Admissions

The World’s Top Dental Schools: 2017 Edition