Periodontal disease has reached levels of epidemic proportions, with gingivitis/periodontitis estimated to affect as many as 75% of the adult population in their lifetime. There are also an increasing number of consumers who have read about the possible association of periodontal disease to serious medical risks. The US Surgeon General issued a report in 2000 that presented some interesting statistics about oral health.1 It indicated that employed American adults lose more than 164 million hours of work annually due to dental disease and emergency dental visits. Predictably, those who got biannual dental checkups usually caught oral health concerns early on.

New science and the latest understanding of periodontal disease now makes it possible for a knowledgeable dentist to provide successful dental care to reduce risk for oral and physical disease with a course of conservative periodontal treatment.

ORAL-BODY INFLAMMATORY CONNECTION

The connection between dental disease and cardiac disease has been recently documented. In 2005, after studying the relationship between periodontal bacteria and atherosclerosis (narrowing of the carotid arteries), Desvarieux et al2 reported that periodontal disease can contribute to cardiovascular disease (CVD) and can be a major risk for death. He also showed that chronic periodontal disease may be a possible cause of CVD.

A paper published in 2010 in the British Medical Journal3 correlated tooth brushing, inflammation, and the risk of CVD from a Scottish Health Survey. Close to 12,000 participants, both men and women, with a mean age of 50 years, were studied. Oral hygiene was assessed from the self-reported frequency of tooth brushing. The reported poor oral hygiene was associated with a higher risk of low-grade inflammation and higher levels of CVD.

Because of the oral-body inflammatory connection (OBIC), clinical treatment studies have been performed to evaluate the effect that treatment of periodontal disease has on the degree of heart disease present. In April 2009, Piconi et al4 published a study showing that the treatment of periodontal disease reduced the narrowing of the carotid artery and resulted in an improvement in the atherosclerosis.

Slepian and Gottehrer5 in 2009 described the OBIC and discussed many of the inflammatory enzymes as being involved in patients with CVD. This has finally led to an understanding of how periodontal disease develops and progresses, leading to technology which now allows the disease to be stabilized and controlled. The following year, they authored a guide entitled Evaluation and Management of the Oral Body Inflammatory Connection Resource Guide. (This guide was published as a courtesy for all the practicing dentists in the United States by Chase Health Advance Financing Options.) It describes in detail both this critical connection and the effective, nonsurgical management of periodontal disease.

In September 2010, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Oral Health completed a National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES) published in the Journal of Dental Research,6 which found gum disease to be a significant health concern. NHANES has historically been the main source for determining the status of periodontal disease in the US adult population. Comprehensive periodontal exams were conducted on more than 450 adult patients over the age of 35 years. The prevalence rates were compared against previous NHANES studies, which only used a partial mouth periodontal exam. The previous studies had shown prevalence of both gingivitis and periodontitis as high as 56% in adults. The present study found that the original methodology may have understated the disease prevalence by up to 50%. These figures could easily be interpreted to represent periodontal disease as the most common disease present in the body today.

|

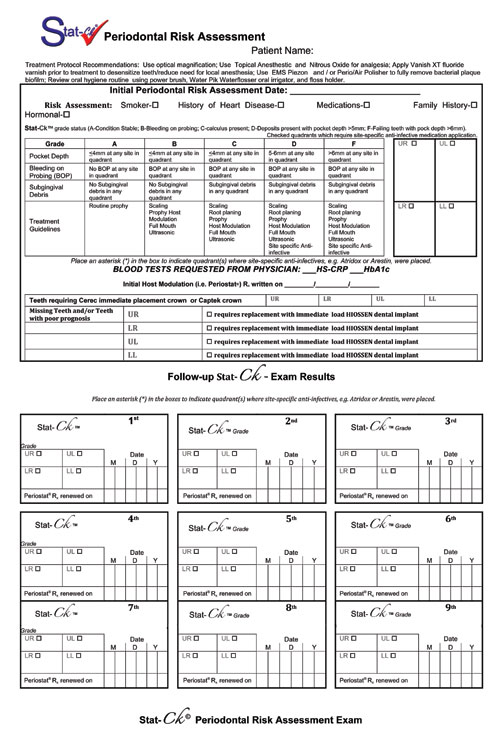

| Figure 1. Stat-Ck Periodontal Risk Assessment documentation record used for periodontal risk assessment at the initial visit. |

ORAL BACTERIA CAN RESULT IN BLOOD CLOTS

A recent study in 20107 has discovered how bacteria in the mouth that results in tooth decay can also cause blood clots. While the study was conducted in small lab animals, it was hypothesized that poor dental hygiene conditions could lead to bleeding gums, providing the bacteria, even in gingivitis, an escape route into the blood stream. It can initiate blood clots resulting in heart disease. Streptococcus bacteria, normally present in the oral biofilm, can result in both gum disease and tooth decay. Upon entering the bloodstream through bleeding gums, they produce a protein that brings together platelets from the blood to form a clot which results in thrombosis.

THIRD PARTY VERIFICATION OF DISEASE

Considering the risk of these diseases, it is important for all patients (even those who present without active symptoms of disease) to see for themselves in the dentist’s office verification of how dental care can reduce the serious risk of disease. The simplest way to illustrate this is through third-party verification. Short duration (one to 2 minutes) in-office patient education video programs (such as CAESY [Patterson Dental]) illustrate the connections and provide verification of what the dentist/hygienist has said, confirming the need for periodontal management. Patients who have viewed these videos often comment that they wish they had been presented with this very important information earlier in life; they know that it might have prevented them from developing and suffering from their current problem.

PERIODONTAL RISK ASSESSMENT

Since less than 10% of patients who have periodontal disease are receiving treatment, a periodontal risk assessment should be performed on all new and existing patients. A common assessment now being used by many dentists is the Stat-Ck Periodontal Risk Assessment (PRA) It was developed in 2002 by Gottehrer and Shirdan.8 The first part of the assessment records a history of smoking, history of heart disease, medications taken, and for females, any hormonal problems.

The risk assessment is designed to provide information for both the dentist and patient concerning the present periodontal status. It is done to determine if there is active disease present by examining all the teeth circumferentially with a periodontal probing; grading each of the quadrants following the traditional test format of A to F. A is asymptomatic; B presents with bleeding; C with calculus above the gum; D with deposits below the gum; and F signifies a failing area. The categories are listed and described in the risk assessment chart, as pictured in Figure 1. The patient must participate in the screening probing by observation with a full-size patient mirror. When active disease is present, patients will see bleeding from the periodontal tissue which most likely they have not even seen when brushing. This can be the most positive confirmation of the presence of disease, affirming the need for interventional treatment.

The Stat-Ck PRA replaces the periodontal screening and recording as a screening test with actual results recorded rather than a recommendation for further evaluation. Unlike a traditional 6-point probing which must be performed once the patient begins treatment, the A to F format is more easily understood by patients, thus allowing a simple way for them to understand their current periodontal status. The patient should participate in the screening probing, observing bleeding from the periodontal pocket that occurs when the probing is done; remember that this bleeding may not have been seen with routine brushing/flossing of the same areas. This confirms for the patient that active disease is present. Once the probing is completed, it must be explained to the patient that this bleeding is not normal.

The Stat-Ck PRA explains the results of the screening, with suggestions for treatment for each category. It can include suggestions for removal of hopeless teeth and placement of crowns, or appropriate restorations to control and/or reduce risk for recurrent decay.

ROLE OF THE PERIODONTIST

A major resource impacting patient acceptance of this critical treatment is the periodontist. More periodontists are increasingly playing an active role in the management of the patient when nonsurgical care is the treatment plan. Many are even offering complimentary verifications to assist the patient in decisions with regard to treatment.

Since periodontal disease now appears to have a possible systemic impact on our patients’ health, a team approach to care involving both the periodontist and general practitioner as well as the hygienist is even more critical. Periodontists can also help to provide regenerative treatment to supplement nonsurgical care, whenever required. The whole team can provide treatment that stabilizes function and can now effectively control the active disease long-term.

|

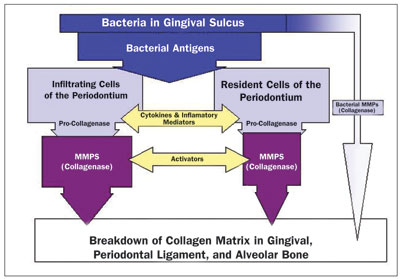

| Figure 2. Host response to bacterial antigens produces periodontal breakdown. (Reprinted from: Gottehrer N. Managing Risk Factors in Successful Nonsurgical Treatment of Periodontal Disease. Dent Today. 2003;22:64.) |

In 1997, Kornman et al9 first summarized the various host-derived mediators present in both the gingival crevicular fluid and periodontal tissues that may contribute to periodontal tissue destruction, including cytokines that mediate inflammation, active osteoclasts that destroy bone, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) which breakdown major structural tissue in the periodontal complex (Figure 2). Golub and associates,10 in 1994, developed subantimicrobial dose doxycycline (SDD) (20 mg twice per day) to treat periodontal disease by blocking these tissue-destructive enzymes.

In 2007, Caton et al11 described periodontal treatment with this SDD drug to improve the efficacy of scaling/root planing in adult patients with periodontal disease. It can now be considered the standard of care for nonsurgical periodontal treatment in reducing the dental risk for cardiac disease.12 This standard of care allows for anticipated, predictable, and successful long-term stabilization of the patient’s periodontal condition. A standard of care for the nonsurgical management of periodontal disease is required if dentists are to provide highly predictable results in periodontal management; the future of successful dental care.

This suggests that dentists should use site-specific treatment to manage periodontal disease, supported by evidence-based technology. This includes the use of toothpaste and mouthwash with power hygiene devices, including battery operated tooth brushes and electric powered water irrigators, such as the new Waterpik Water Flosser (WP-100), ultrasonic and hand instrumentation and placement of time released locally applied antimicrobial drugs below the gingival margin into periodontal pockets with 5 mm of depth or more and bleeding on probing. While use of interproximal cleaning with dental floss is still encouraged, recent evidence shows that use of a powered toothbrush appears to be as effective as manual brushing combined with interproximal cleaning.13 Predictable and successful long-term stabilization of the patient’s periodontal condition now relies on this specific home hygiene management program. This must be done at least twice per day to remove the offending bacteria both above and below the gingival margin.

Water irrigation (“water flossing” [Water Flosser]) should be done immediately following brushing if removal of all the offending bacteria is to be achieved. It has been shown to outperform traditional flossing with recent clinical research confirming that the Water Flosser is twice as effective as string floss in reducing gingival bleeding after 14 days of use.14 It has also been shown to significantly reduce plaque biofilm, gingivitis, and bleeding and pocket depth in periodontal patients. In addition, it has also been proven to reduce cytokines in the gingival crevicular fluid; it produced a host modulation effect by reducing interleukin (IL) 1 and Prostaglandin E2, cytokines associated with bone and attachment loss, raising IL-10, an anti-inflammatory agent. It has been proven that the addition of the Water Flosser to the patient’s armamentarium for use in carrying out daily oral hygiene inhibits the activity of periodontal disease and significantly improves periodontal health.15

IMPACT OF SYSTEMIC DRUG MANAGEMENT ON PERIODONTAL HEALTH

In March 2011, Payne et al16 completed a 2-year study using SDD to reduce systemic biomarkers including serum inflammatory MMP and high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP). There was also a statistically significant increase in high-density lipoprotein (good) cholesterol in women more than 5 years postmenopausal. Alveolar bone density loss was reduced. Clinical attachment levels were stabilized. SDD and periodontal maintenance decreases the odds of more progressive periodontitis by 19% relative to placebo.

Ridker et al17 did significant research to identify hsCRP as a systemic inflammatory biomarker, reporting it to be more predictive of cardiovascular events than elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels.

LOCAL DELIVERY OF SITE-SPECIFIC ANTIMICROBIAL DRUGS

The local delivery of antimicrobials, such as Arestin (Orapharma), offer the dentist a statistical and significant system for the treatment of periodontitis.18 The Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (the federal agency assigned to improve quality, safety, efficiency, and effectiveness of healthcare) evaluated literature on these antimicrobials in 2004.19 They concluded that scaling/root planing, when accompanied by the placement of an antimicrobial agent (Arestin) as a supplement or adjunct treatment, resulted in an improved clinical outcome in adults with chronic periodontitis. (This was compared to scaling/root planing that was done alone.) Systemic and locally placed antimicrobial drugs are therefore suggested for use when active disease is detected. They have clearly shown in the studies mentioned to be of significant help in resolving the diseased condition and restore periodontal health as quickly as possible.

Patients usually understand medical treatment with medication. It is a natural addition to periodontal treatment, following the medical model. These drugs can be used on a routine basis as a standard of care, in successfully managing periodontal disease.

ROLE OF PROBIOTICS IN MANAGING PERIODONTAL DISEASE

Periodontal disease may be impacted by the use of new probiotic products, such as GUM PerioBalance (Sunstar Americas) and Evora Plus (Oragenics). Probiotics consist of microorganisms in oral tablet/lozenge form that confer a health benefit to the patient. Current research has indicated that periodontal disease may be impacted by probiotics through the reduction of the body’s inflammatory mediators. Twetman et al20, in 2009, using 2 strains of Lactobacillus reuteri, found that there was a reduction in bleeding on probing and the amount of cytokines present in the gingival crevicular fluid, a reduction in the periodontal inflammatory response. This may help to reduce oral disease. GUM Perio Balance is designed to be used once daily, immediately following flossing and brushing. The lozenge dissolves in the mouth in 10 minutes, and it is recommended that nothing be used in the mouth immediately after the use of the lozenge for 30 minutes (Figure 3).

|

|

| Figure 3. Monthly oral probiotic lozenge system (GUM PerioBalance [Sunstar Americas]) for once-a-day use. | Figure 4. Gold collar (Captek crown [Precious Chemicals]) submerged in subgingival margin. |

EFFECT OF NONSURGICALINSTRUMENTATION ON PERIODONTAL DISEASE

In order to obtain a predictable and stable periodontal condition, using the mechanical hygiene techniques and the SDD and the suggested site-specific antimicrobials, mechanical instrumentation with scaling and root planing is required. A 2002 literature review21 of mechanical instrumentation exclusively confirmed that pockets measuring 4 to 6 mm experienced a mean reduction probing depth of 1.29 mm with an additional net gain in attachment of 0.55 mm. Periodontal pockets with an initial probing depth of greater than 7 mm experienced reduction of mean probing depth of 2.16 mm and a gain in attachment of 1.19 mm.

A 6-month randomized, multicenter, placebo-controlled, examiner-masked study was undertaken by Novak et al22 in 2008. They evaluated the clinical usefulness of a combination treatment of systemically delivered SDD twice per day, plus locally delivered antimicrobial, in combination with scaling and root planing, versus scaling and root planing and placebo (control group) on clinical measures of periodontal disease. The study’s results support the use of a combination of adjunctive therapies for the nonsurgical management of chronic periodontitis. At 6 months, 3 times as many subjects in the combination group had no residual pockets less than 5 mm, compared to the placebo control group. Pocket depth reduction to less that 5 mm occurred more rapidly and more extensively with combination therapy.

PAINLESS MANAGEMENT OF DISEASE

One barrier to consumer acceptance of even conservative nonsurgical periodontal treatment is still the fear of pain. Treatment must be provided painlessly, if at all possible. In order to achieve this, analgesia must be used. It has been estimated that 15% of the US population declines dental care primarily because they fear oral injections.23 Nitrous oxide/oxygen analgesia relaxes patients and reduces their anxiety enough to allow treatment without pain. New technology allows the use of digital flow meters, such as the Porter Instrument Conscious Sedation Flowmeter. To achieve a successful result, analgesia must be available for the patients who require it. A recent innovation (developed by the author) using topical anesthetic spray (such as Hurricane [Beutlich Pharmaceutical]) and a light-cured extended contact topical fluoride varnish (such as Vanish XT [3M ESPE]), makes it possible to perform scaling/root planing without having to use injectable local anesthetics. Previously sensitive roots, which could only be instrumented after administering local anesthetic, can now be treated after a single application of Vanish XT. After being light-cured, the fluoride varnish seals the roots with a durable layer of protection, thus relieving dentinal hypersensitivity and permitting the painless instrumentation and removal of all deposits. Being able to control root sensitivity, while improving the integrity of the root of the tooth where the toxic bacteria collects, gives the dentist/hygienist the opportunity to help control the risk of disease. Reduction of this sensitivity via an extended contact topical fluoride varnish (that can last up to 6 months) can also help to improve patient compliance for performing the required at-home daily hygiene routine; thus making it easier to control the chronic disease risks and improving the future success of dental care.

PERIO IMPLICATIONS OF RESTORATIVE MATERIALS AND MARGIN PLACEMENT

Dental crown restorations are considered a major contributing factor in the etiology of periodontal disease. Löe24 in his classic 1968 paper, reviewed the reactions of the periodontal tissues to restorative procedures. His paper reviewed the reactions of the periodontal tissues and the effect of certain restorative materials on the periodontal tissues.

While optimal periodontal health is expected to the improve success of dental care, it cannot overcome the effect of a crown restoration that extends into the subgingival area and may be responsible for causing damage to the periodontal tissue. This can occur by increasing the possibility for mechanical retention of bacteria and/or by a direct irritation effect from using a restorative material that retains more dental plaque.

Amsterdam25 wrote a classic treatise on periodontal prosthesis more than 30 years ago, establishing the standard of care for a crown. He described the optimal margin/finish line which should be placed in a healthy sulcus at a minimal depth, just shy of the junctional epithelium. In guidelines still followed today, he suggested that to prevent plaque buildup, it is necessary to create optimal crown contours with proper coronal form, embrasure form, and subgingival fit at the margin.

If periodontal health is to be considered the future of success for dental care, it is imperative to use restorative materials which can help maintain a healthy periodontium. Captek (Argen) provides one example of a cosmetic (crown) restorative material that is compatible with excellent periodontal health, helping to satisfy the goal of optimal tissue health. This ceramometal crown incorporates the use of a unique metal composite gold cosmetic coping. The metal can be extended to the edge, developed into a collar, or cut back from the margin for a ceramic butt margin depending on the preparation, margin placement, and/or underlying prep tooth color. When the Captek gold was in the approximation of the margin, Goodson et al26 were able to document a reduction of up to 91% in the number of bacteria surrounding this tooth versus normal tooth surfaces in the same mouth. In addition, they documented 96% less bacterial adhesion compared to conventional ceramic-fused-to-noble-metal crown restorations. These crowns have been described by the author as the “periodontal crown,”27 since healthy tissue can be achieved from placement of the 22K gold margin against the subgingival tissue on any periodontally-affected tooth (Figure 4).

For success to be achieved in dental care, it is essential that materials be fabricated in a manner that makes every attempt to develop periodontally healthy crowns, so as to prevent and/or reduce tissue inflammation. With the introduction of zirconia metal-free crowns, produced from pucks made from high quality zirconia powder (produced by TOSOH), the author employs a coping design modification to maximize soft-tissue health and protection against inflammation. One benefit of zirconia crowns is that they can be adapted to accommodate multiple finishlines at the margin, much like a traditional PFM. The “Periodontal Collar” for zirconia crowns was designed by the author and fabricated by Shaun Keating, owner of Keating Dental Arts Lab. (This dental laboratory was selected by Dr. Gottehrer based on its ability to reengineer new technology successfully.)

The collar is designed to allow removal of bacterial plaque on a regular basis to maintain optimal periodontal health. The subgingival collar is polished using a special material and, because of the special polishing process a very smooth surface is established.

Preliminary observations by Dr. Gottehrer and Keating Dental Arts Lab, with insertion of 50 Periodontal Collar zirconia crowns, have produced healthy gingival responses. The zirconia can be made in a CAD/CAM environment and offers benefits in the way of high hardness factors and fracture resistance. Becoming more familiar with the healthiest coping designs can create optimal periodontal health resulting in long-term success.

Restoring a tooth with compromised periodontal health with an appropriate full-crown, using modern materials that are shown to reduce the risk of additional plaque retention or a negative inflammatory response, should now be considered the treatment of choice for maintaining prolonged dental health.

DENTAL IMPLANTS: HEALTH RISKS OF MISSING TEETH

A Swedish study, completed in 2010, examined the number of teeth a patient has as a predictor of cardiac mortality.28 A group of 7,674 patients were followed for 12 years. The study results showed a relationship between the number of teeth and cardiovascular disease. There was a 7-fold increased risk for mortality from cardiovascular heart disease in subjects with fewer than 10 teeth, as compared to those with more than 25 teeth.

With the knowledge that there can be a very strong connection between periodontal disease and CVD, it is very important to consider permanent replacement of teeth lost to disease. This must now be considered an important part of restoring periodontal health. It can allow the dentist to restore health to a mouth suffering from the loss of permanent teeth.

With the development of new designs in dental implants, such as seen with Hiossen, it is possible to immediately place implants at the time of extraction and often, because of design, immediately load these implants with a prefabricated abutment post and temporary crown. It is also possible, with the new modified designs such as platform loading, to prevent periodontal destruction and bone loss, which was previously observed in implants used without this design.29

CLOSING COMMENTS

The future of periodontics and the opportunity to improve success for dental care is very promising. There also appears to be a great opportunity to reduce certain medical risks with periodontal care, and for dentists to work in concert with physicians to reduce certain risks.

With periodontal risk assessments and screening exams done for patients who need treatment and/or have serious medical conditions, which may be improved, or have risk reduced with periodontal care, team management from the dentist and physician is a reality. The anticipated outcome of successful dental care may benefit everyone, the end results being a healthier population, lowered costs of medical care, and possibly a longer, more comfortable life.

References

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2000.

- Desvarieux M, Demmer RT, Rundek T, et al. Periodontal microbiota and carotid intima-media thickness: the Oral Infections and Vascular Disease Epidemiology Study (INVEST). Circulation. 2005;111:576-582.

- de Olivera C, Watt R, Hamer M. Toothbrushing, inflammation, and risk of cardiovascular disease: results from Scottish Health Survey. British Medical Journal. 2010;340doi:10.1136/ bmj.2451.

- Piconi S, Trabattoni D, Luraghi C, et al. Treatment of periodontal disease results in improvements in endothelial dysfunction and reduction of the carotid intima-media thickness. FASEB J. 2009;23:1196-1204.

- Slepian M, Gottehrer NR. Oral-body inflammatory connection. Dent Today. 2009;28:140-142.

- Eke PI, Thornton-Evans GO, Wei L, et al. Accuracy of NHANES periodontal examination protocols. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1208-1213.

- Petersen HJ, Keane C, Jenkinson HF, et al. Human platelets recognize a novel surface protein, PadA, on Streptoccocus gordonii through a unique interaction involving fibrinogen receptor GPIIbIIIa. Infect Immun. 2010;78:413-422.

- Gottehrer NR, Shirdan TA. A new guide to nonsurgical management of periodontal disease. Dent Today. 2002;21:54-59.

- Kornman KS, Page RC, Tonetti MS. The host response to the microbial challenge in periodontitis: assembling the players. Periodontol 2000. 1997;14:33-53.

- Golub LM, Wolff M, Roberts S, et al. Treating periodontal diseases by blocking tissue-destructive enzymes. J Am Dent Assoc. 1994;125:163-169.

- Caton JG, Ciancio SG, Blieden TM, et al. Treatment with subantimicrobial dose doxycycline improves the efficacy of scaling and root planing in patients with adult periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2000;71:521-532.

- Gottehrer NR, Martin JL. The standard of care for nonsurgical periodontal treatment for reducing the dental risk for cardiac disease. Dent Today. 2007;26:100-104.

- Axelsson P. Mechanical plaque control by self-care. In: Axelsson P. Preventive Materials, Methods, and Programs, Volume 4. Chicago, IL: Quintessence Publishing; 2004:80-101.

- Barnes CM, Russell CM, Reinhardt RA, et al. Comparison of irrigation to floss as an adjunct to tooth brushing: effect on bleeding, gingivitis, and supragingival plaque. J Clin Dent. 2005;16:71-77.

- Cutler CW, Stanford TW, Abraham C, et al. Clinical benefits of oral irrigation for periodontitis are related to reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokine levels and plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:134-143.

- Payne JB, Golub LM, Stoner JA, et al. The effect of subantimicrobial-dose-doxycycline periodontal therapy on serum biomarkers of systemic inflammation: a randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:263-273.

- Ridker PM, Rifai N, Rose L, et al. Comparison of C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the prediction of first cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1557-1565.

- Killoy WJ. The clinical significance of local chemotherapies. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29(suppl 2):22-29.

- Bonito AJ, Lohr KN, Lux L, et al. Effectiveness of antimicrobial adjuncts to scaling and root-planing therapy for periodontitis. Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 88. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; January 2004. ahrq.gov/ clinic/epcsums/periosum.htm. Accessed September 8, 2011.

- Twetman S, Derawi B, Keller M, et al. Short-term effect of chewing gums containing probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri on the levels of inflammatory mediators in gingival crevicular fluid. Acta Odontol Scand. 2009;67:19-24.

- Cobb CM. Clinical significance of non-surgical periodontal therapy: an evidence-based perspective of scaling and root planing. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29(suppl 2):6-16.

- Novak MJ, Dawson DR III, Magnusson I, et al. Combining host modulation and topical antimicrobial therapy in the management of moderate to severe periodontitis: a randomized multicenter trial. J Periodontol. 2008;79:33-41.

- Capps Bowman Padgett and Associates. Dental phobia. cappsbowman.com/sep/greenville-dental-phobia.htm. Accessed September 8, 2011.

- Löe H. Reactions of marginal periodontal tissues to restorative procedures. Int Dent J. 1968;18:759-778.

- Amsterdam M. Periodontal prosthesis: Twenty-five years in retrospect. Alpha Omegan. 1974;67:8-52.

- Goodson JM, Shoher I, Imber S, et al. Reduced dental plaque accumulation on composite gold alloy margins. J Periodontal Res. 2001;36:252-259.

- Gottehrer NR. The periodontal crown: creating healthy tissue. Dent Today. 2009;28:121-123.

- Holmlund A, Holm G, Lind L. Number of teeth as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality in a cohort of 7,674 subjects followed for 12 years. J Periodontol. 2010;81:870-876.

- Gottehrer NR. Implant dentistry: replacement of missing teeth with predictable crestal bone levels. Compendium. 2011;32(suppl 1):12-15.

Additional Reading

Evaluation and Management of the Oral Body Inflammatory Connection, Resource Guide recently written by Neil R. Gottehrer, DDS, and Marvin J. Slepian, MD, has been printed for the practicing dentist as a courtesy by ChaseHealthAdvance Financing Options. It is available from ChaseHealthAdvance at no charge by calling (888) 388-7633. This resource guide explains in greater detail the process of evaluation and successful management of periodontal disease, and can make it easier for dental practices to achieve positive results with their patients.

Dr. Gottehrer has been in practice in suburban Philadelphia, Pa, for more than 30 years, focusing his practice on cosmetics, implant dentistry, and periodontics. He is a graduate of the University of Maryland Dental School, received his postgraduate periodontal training at the University of Pennsylvania, and is a board-certified periodontist. He teaches the senior elective course in periodontics at the University of Maryland Dental School. He has published and lectured internationally, and is currently the president of the Institute of Advanced Oral and Physical Health in Havertown, Pa. He is the recent recipient of the The William J. Geis Memorial Award from the American Dental Education Association Gies Foundation. He can be reached at (610) 449-9500 or at dr.neilg@verizon.net.

Disclosure: Dr. Gottehrer reports no disclosures.