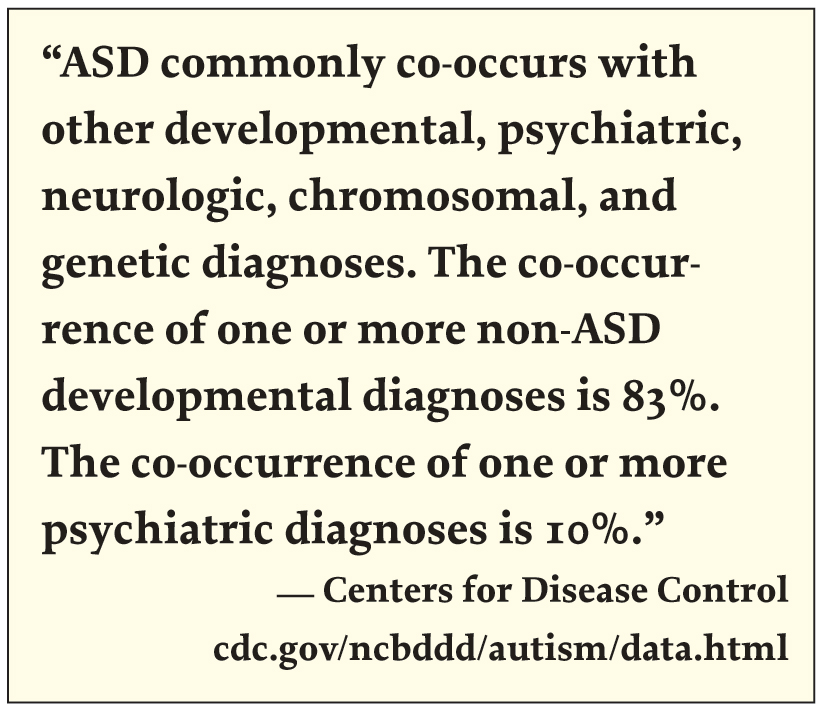

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported in March 2014 that the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is currently one in 68.1 This number represents one out of 42 boys and one out of 189 girls.1 These numbers continue to increase with each passing year. According to Autism Speaks, more children are affected by ASD than by diabetes, AIDS, cancer, cerebral palsy, cystic fibrosis, muscular dystrophy, or Down syndrome combined. As dental professionals, it would be prudent that we learn more about ASD and how to adapt our skills to better serve this population.

Dental hygienists are frontline, primary oral healthcare providers. Our patients, their families, and our colleagues look to us for preventive oral healthcare treatment and solutions. Awareness of ASD and knowledge of strategies to improve the dental experience for individuals on the spectrum will improve the dental appointment for these patients and, in turn, improve their oral health.

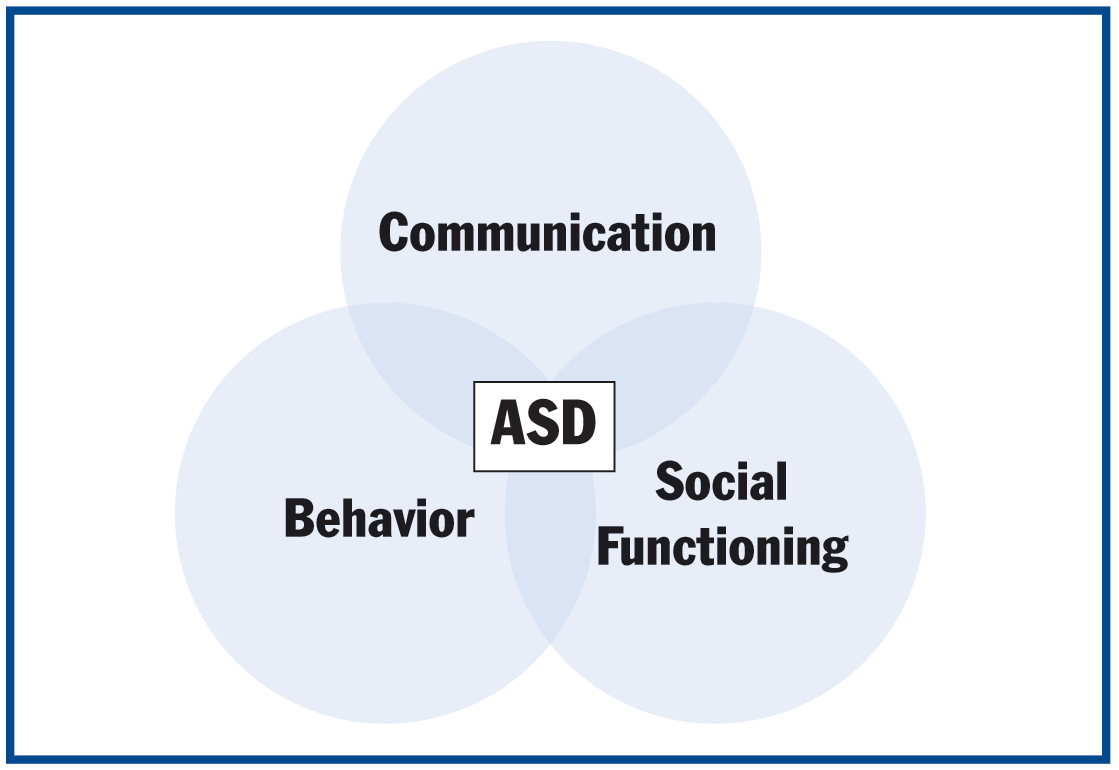

|

| Figure 1. The relationship of autism spectrum disorder and common characteristics. |

WHAT IS AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER?

ASD is a complex neurological dysfunction of the brain that results in a lifelong developmental disability. Individuals with ASD demonstrate impairments in communication, social functioning, and behavior (Figure 1). It is important to remember that it is a “spectrum” disorder, meaning individuals can present with symptoms ranging from mild to severe.

In March 2013, The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (fifth edition) was published with a merging of the previous subtypes of autistic disorder, Asperger’s syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder—not otherwise specified, and childhood disintegrative disorder into one diagnosis of ASD.

COMMON CHARACTERISTICS

Communication

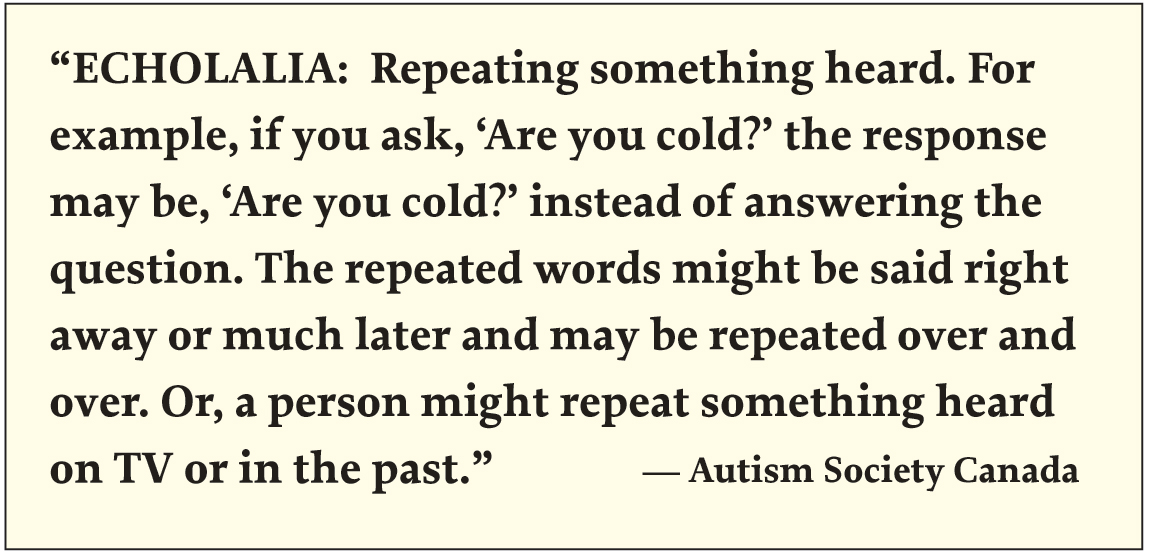

Up to 25% of individuals on the spectrum are nonverbal.2 This condition should not be mistaken for an inability to comprehend, however. Many individuals with ASD may lack the ability to speak but have no difficulties with receptive language. Communication deficits may include impaired language skills and/or a lack of understanding. Another consideration is the lack of understanding of nonverbal gestures—many individuals on the spectrum miss the subtleties and nuances of nonverbal communication that many of us take for granted. Many do not understand or may misinterpret facial expressions, while others may experience echolalia. Additionally, much of a face-to-face conversation can be lost without the ability to maintain eye contact.

Social Functioning

Typically, for individuals with ASD, social interactions are impaired. Many people on the spectrum may appear to have an aloof manner and most have difficulty with eye contact. Additionally, difficulty in recognizing other people’s feelings, inability to read facial expressions, and often inappropriate laughing or giggling can hinder most social situations. Many individuals with ASD fail to develop social attachments; this is demonstrated with poor peer interactions and a preference to keep a physical and emotional distance from others.

|

Behavior

There are stereotypical behaviors associated with ASD. Many can demonstrate obsessive interest or fixations and/or inappropriate attachment to objects. Individuals on the spectrum may have an apparent lack of common sense or awareness of potential dangers. Some may seem very passive, while others can be extremely overactive. Many demonstrate opposition to changes in routine and may insist on sameness. Most significantly, many individuals with ASD demonstrate self-stimulatory behaviors, often called “stimming,” that can be prompted by sensory sensitivities of sight, hearing, touch, smell, and/or taste. Stimming is a repetitive action that can manifest in many ways for someone with ASD depending on the individual, but often is demonstrated by head-banging, hand-flapping, rocking, spinning, or finger-wringing. (See the Additional Reading list for more information.)

CO-ASSOCIATED CONDITIONS

Sensory Problems

Altered responses to sensory stimuli of sounds, sights, touch, taste, textures, and smells are common in individuals with ASD. Some may overreact to the slightest of touch while others may have little or no response to extreme pain. When the sensory stimuli are intolerable or completely overwhelming, an individual may experience a “meltdown,” resulting in atypical, self-injurious behaviors, or stimming. This can often be mistaken for a tantrum, which is very different. Quite often people with autism are misunderstood and believed to be noncompliant, when in reality they may be experiencing physical pain or discomfort due to sensory overload.

|

Intellectual Disability

An estimated 40% of individuals on the spectrum also have an intellectual disability.2 Many have lower cognitive abilities but test higher in other abilities. Generally, language-based learning is problematic, but visual or rote abilities may be exceptional. Individuals with what was once considered Asperger’s syndrome usually have higher IQs and no delays in language or cognitive abilities.

Seizure Disorder

One in 4 individuals with autism experience seizures.3 Some experience seizures throughout childhood, while others begin to experience them at adolescence. The seizures may present as convulsions, involuntary body movements, a blank stare, or an intermittent loss of consciousness.

Genetic Conditions

Fragile X syndrome, Down syndrome, and tuberous sclerosis are 3 most commonly seen genetic conditions co-morbid to ASD. About one in 3 children diagnosed with fragile X syndrome also meet the criteria to be diagnosed with ASD.3 One percent to 10% of individuals with Down syndrome also have a dual diagnosis with ASD.4 Tuberous sclerosis is a condition in which noncancerous tumors grow on vital organs. Approximately 1% to 4% of individuals with ASD also have this rare genetic condition.3

|

|

| Figure 2. The author working with patient “S.” | Figure 3. The author working with patient “M.” |

Gastrointestinal Problems

The CDC reports that up to 85% of individuals with ASD experience gastrointestinal problems that can range from chronic constipation to diarrhea, bloating, stomach pain, and acid reflux. Behavioral difficulties are believed to be prompted by frequent gastrointestinal problems. Some food allergies or intolerances have been associated with ASD, and some families adopt a gluten- and casein-free diet to help alleviate some of these symptoms.

Co-Associated Mental Disorders

Individuals with ASD often have mental health disorders including anxiety, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Autism Speaks indicates that more than two thirds of those with ASD also have a co-associated psychiatric disorder.2

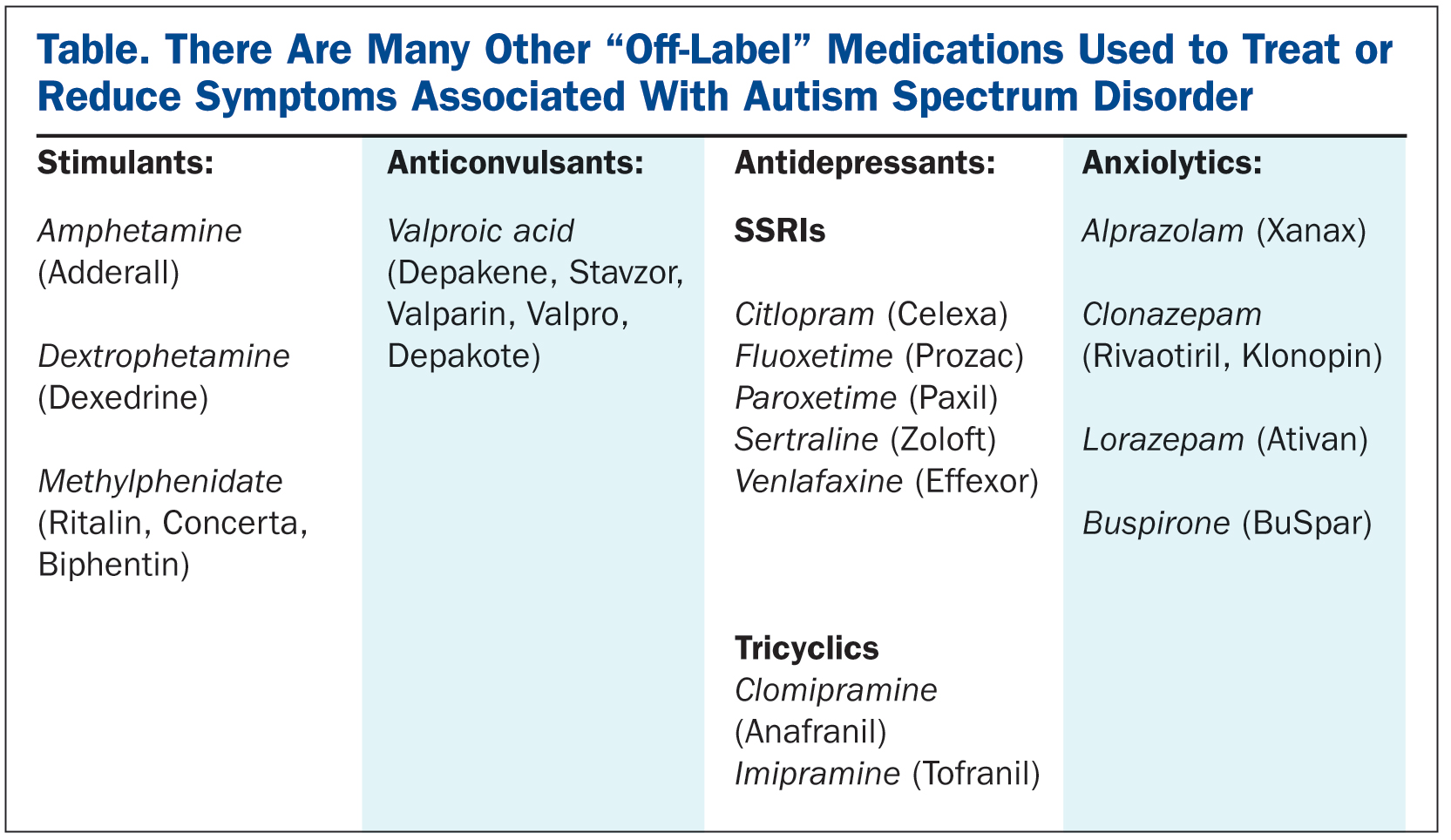

Medications

To date, there are no medications that can cure, treat, or eliminate all of the symptoms of ASD. There are only 2 approved medications specifically used to treat symptoms associated with ASD: risperidone (Risperdal) and aripiprazole (Abilify); both are antipsychotic drugs. These help by treating irritability associated with ASD; in turn, this can improve sociability, decrease frequency of tantrums and meltdowns, reduce aggressiveness, and self-injurious behaviors.

There are also many other “off-label” medications that are used to treat or reduce the symptoms associated with ASD (Table).

|

DENTAL CONSIDERATIONS AND COMMON ORAL HEALTH CONDITIONS

Caries Considerations

The several factors that put individuals with ASD at risk for caries are as follows:

- Oral hygiene may be of low priority for parents/caregiver of individuals with higher needs and behavioral issues.

- Dietary choices can be restrictive and with preference to highly cariogenic foods.

- Food used as motivators in behavior modification and therapies results in frequent snacking.

- Brushing and flossing can be very overwhelming for individuals on the spectrum; sensory aversions can result in inadequate oral hygiene.

- Fine and gross motor deficits may result in improper chewing and swallowing. There may be pouching of food in buccal vestibules. The natural self-cleansing habits of the tongue and cheeks may not be strong in individuals with ASD.

Although at higher risk, there is evidence to indicate that children and adolescents on the spectrum actually have a lower incidence of caries and have lower DMFT scores.5,6

Bruxism

Individuals with ASD, as with those with other developmental disabilities, have a higher incidence of clenching and grinding. Higher levels of anxiety and sensory disorders may be contributory to bruxism.

Pica and Rumination Disorder

Pica is the ingestion of nonfood/non-nutritive substances. Frequently observed ingested articles are:

- Mud/dirt

- Pottery

- Clay

- Chalk

- Hair

- Feces

- Cigarette butts/ashes

- Laundry detergent

- Soap

- Buttons

- Nails/metal

- Paper

- Paint/paint chips

Not only should we consider the overall health concerns of pica, but also the consequence of ingesting such articles and the increased potential for significant damage to both hard and soft oral tissues.

Rumination is the regurgitation of partially digested food. This is done with minimal effort, and it is not considered vomiting or reflux. Rumination is commonly seen in individuals with developmental disabilities, and it is thought to be a self-stimulatory or soothing behavior. There are significant medical consequences to this behavior as well as dental consideration of caries, halitosis, ulcerated esophagus, and an increased potential for periodontal disease.

Tongue Thrusting

Tongue thrusting is commonly seen in individuals with developmental delays. Some also consider this and other mouthing behaviors as a form of stimming. Facial and dental development can be affected with tongue thrusting behaviors and can result in malocclusion.

Self-Injurious Behaviors/Trauma

Individuals with ASD frequently participate in self-injurious behaviors that can result in significant dental damage. Some may habitually pick at lips and/or gums. Behaviors such as repetitive head banging and hitting oneself in face and/or head can result in oral trauma.

Individuals on the spectrum may be unaware of potential dangers, and those with gross and/or fine motor deficits may be more prone to accidents and falls that can result in significant dental trauma.

Erosion

Commonly associated digestive disorders, such as GERD, are frequently seen in individuals on the spectrum resulting in dental erosion. Dietary choices and beverages consumed may also be contributory.

Xerostomia

Medications used to treat symptoms associated with ASD frequently affect salivary function. Dry mouth is the most common side effect of many of the prescribed medications.

Periodontal Diseases

All of the above mentioned factors are contributory to gingivitis and periodontal disease commonly observed in adults with ASD.

THE CHAIRSIDE EXPERIENCE

Communication with parents or caregivers is recommended prior to the initial appointment. This allows the dental hygienist to discuss medical history, review medications taken, and to determine if there are any co-morbid conditions present. Be sure to discuss if there are any anticipated sensory, communication, and/or behavioral issues, and be aware of any intellectual/cognitive deficits. Assess if consultation with other health professionals is required prior to the appointment. You are more likely to be successful if you are prepared! (See Additional Reading list.)

Individuals on the spectrum will be more comfortable if they know what to expect. Prior to the initial appointment, have the client become familiar with your office. This can happen with use of a social story or books explaining dental healthcare. Sharing photos of dental office team members will help these patients become familiar (at least visually) with who they will be seeing/meeting at the dental hygiene appointment. Arrange a tour to first meet your treatment and office teams, and to also become familiar with the dental office and operatory. Explain sounds and smells, show the armamentarium, and explain what will happen during the oral care appointment. Offering consistency and predictability will help ensure a more successful dental hygiene appointment.

Choose an appointment time during “off-peak” hours and allow additional time for the appointment. Give your client time to become familiar with the surroundings and more comfortable with you. Some may prefer something to comfort or distract them (blanket, toy, music, videos). Explain each step; show the individual what you will use, allowing him or her to touch, see, and/or smell before you initiate. Then, while reinforcing positive behavior, work at the individual’s pace and comfort level. With every future visit, your client will become more familiar with you and what to expect of the care you offer; therefore greater success with every visit. That being said, if the individual’s behavior puts anyone at risk for injury, perhaps referral to an alternate care setting may be a more appropriate choice for your client (ie, a practice specializing in anesthesia).

Most importantly, be patient. Some clients on the spectrum may have little to no difficultly during dental visits, while others may not even be able to lie back in the chair. Building rapport and trust takes time, but in the end, your client will be better served if you persevere and make the commitment to helping the patient attain better oral health.

Figure 2 demonstrates perfectly that we don’t always need our client to do what we expect for it to be a successful appointment. Patient “S” prefers to sit in the operatory chair instead of lying back, and he doesn’t like wearing a bib or having the overhead light on. “S” is nonverbal and needs the support of his caregiver to get through most dental appointments. I usually offer 2 flavors of paste and fluoride; he will point to his choice preference. In this picture I am explaining the benefits of fluoride to him; although he is nonverbal, I am confident that he understands exactly what we are discussing.

When working with patients who are nonverbal or have limited communication abilities, it is essential that the caregiver/parent is present to be the patient’s voice. As you can see in Figure 3, without the mother of patient “M”, very little would be accomplished. Her mother gently strokes her hair and face while encouraging her throughout her appointments. Her favorite blanket provides comfort. For her, this establishes our office as a nurturing and caring environment in which she feels safe.

HOME CARE

Teaching effective home care routines is the most valuable lesson you can give. Even if every single re-care appointment has limited success, helping implement an effective homecare routine will dramatically improve the quality of your client’s life; this skill is one that will benefit them for the rest of their lives!

Be sure to review oral hygiene instructions with both the patient and the caregiver, giving both verbal and written instructions. Provide suggestions on appropriate positioning techniques, as the caregiver is the one who is providing the daily oral home care routine. Collaboration with other health professionals that your client may be working with may be advantageous. For example, consultation with an occupational therapist can help incorporate adaptive techniques or aids should there be any fine and/or gross motor skill deficits. Also, reinforcement of a required homecare routine can be reinforced with Applied Behavior Analysis programming used by behavioral therapists and alternative communication resources used by speech/language pathologists. As well, parents can ask for oral hygiene routines be added into a child’s individual education plan that can be reinforced at school. (See the Additional Reading list for more information.)

CLOSING COMMENTS

Autism is a complex and multifaceted disorder. Dental treatment for individuals on the spectrum can be challenging for dental professionals, but more so for the client. Patience and perseverance will be your keys to success. Helping individuals with ASD improve their oral health improves their overall health and, in turn, greatly impacts and improves the quality of their lives.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/index.html. Updated April 28, 2014. Accessed May 20, 2014.

2. Autism Speaks. What is autism? autismspeaks.org/what-autism. Accessed May 20, 2014.

3. National Institute of Mental Health. What is autism spectrum disorder? nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/autism-spectrum-disorders-asd/index.shtml. Accessed May 20, 2014.

4. Capone GT. Down syndrome and autistic spectrum disorder: a look at what we know. kennedykrieger.org/patient-care/outpatient-programs/down_syndrome_autism_spectrum_disorders. Accessed May 20, 2014.

5. College of Dental Hygienists of Ontario. CDHO Advisory/Autism Spectrum Disorders. August 1, 2011. cdho.org/Advisories/CDHO_Advisory_Autism_Spectrum_Disorders.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2014.

6. Loo CY, Graham RM, Hughes CV. The caries experience and behavior of dental patients with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1518-1524.

Additional Reading

Autism Speaks. ATN/AIR-P Dental Professionals’ Tool Kit. autismspeaks.org/science/resources-programs/autism-treatment-network/tools-you-can-use/dental. Accessed May 20, 2014.

Free social story of going to the dentist. Available at: leechbabe.files.wordpress.com/2008/08/dentist-social-story.pdf. August, 2008.

Grandin T. Why do kids with autism stim? Autism Asperger’s Digest. November/December 2011. autismdigest.com/why-do-kids-with-autism-stim. Accessed May 20, 2014.

National Museum of Dentistry. Healthy Smiles for Autism: Oral Hygiene Tips for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. dentaletc.umaryland.edu/odar/health_smiles_for_autism.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2014.

Visual supports that can assist in reinforcing home care routines. Available at: educatoressentials.com/product-category/freebies/visual-supports/.

Waldman HB, Perlman SP, Wong A. Providing dental care for the patient with autism. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2008;36:662-670.

Additional Web Sites

National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; National Institutes of Health: nidcr.nih.gov

National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Practical Oral Care for People With Autism: nidcr.nih.gov/OralHealth/Topics/DevelopmentalDisabilities/PracticalOralCarePeopleAutism.htm

Autism Society Canada: autismsocietycanada.ca

Autism Canada: autismcanada.org

Autism Ontario: autismontario.com

Autism Speaks: autismspeaks.com

Autism Foundation Canada: autismcanada.org

The National Autistic Society: autism.org.uk

National Museum of Dentistry: dentalmuseum.org

Ms. Russell is a registered dental hygienist with a 15-year career span in the dental profession. She has diverse work experience, including periodontal and orthodontic practices, but most significantly, a specialty anesthesia practice where she had the opportunity to obtain valuable knowledge and skills working with individuals with special needs and those with dental phobias. Currently, she is a practicing clinical hygienist in general practice as well as an independent dental hygiene practice. She is a continuing education speaker with RDHU (rdhu.ca) and The Unique Dental Hygiene Professional Development Center, with her primary presentation focus on working with individuals with exceptional needs. As a mother of a child with autism spectrum disorder, she advocates not only for her daughter affected by this neurological disorder, but for all individuals with special needs, by helping clients, her peers, and other dental health professionals recognize the unmet dental needs of this population. A committed lifelong learner, she is an active member of Ontario Dental Hygienists’ Association and Canadian Dental Hygienists’ Association, a member of the Dental Hygienist Periodontal Study Club of Toronto, while maintaining an active registration with the College of Dental Hygienists of Ontario. She can be reached via e-mail at nadine-russell@hotmail.com.

Disclosure: Ms. Russell reports no disclosures.