INTRODUCTION

In recent years, following the development of new bonding and restoration materials, there has been a change in the way caries lesions are treated.

Composites, bonding materials, and new ceramic materials enable the doctor to perform restorations in the teeth using an approach that entails minimal preparation, allows optimal preservation of the tooth material, and does not require the mechanical retention of the restoration materials that are necessary in amalgam and crown restorations.

Direct anterior and posterior composite restorations and indirect restorations (veneers, inlays, onlays, and endocrowns) enable dentists to avoid removing healthy tooth material, reducing complications of excess tooth structure removal.1

Two main problems accompany the clinician in this type of restoration. First, the bonding layer undergoes degradation over time, which leads to a weakening of the connection between the tooth material and the restoration material and the creation of a gap that may lead to secondary caries.2

Second, composites and ceramic materials do not have antimicrobial properties. In composite restorations, secondary caries have been detected significantly more frequently in composite than amalgam.

This clinical report will present a complex, minimally invasive treatment that includes direct and indirect restorations in a patient with rampant caries. The direct restorations were carried out with composite and bonding material containing antibacterial particles. The materials were also used as base materials in the indirect restorations.

CASE REPORT

The patient, 36 years old, was treated in a clinic in another geographical area over the past few years. The attending physician referred the patient for treatment in our clinic after being unable to stabilize the rampant caries.

The patient reported that most of the oral treatments had been performed over the past few years, noting that in every visit, the attending physician detected both restorations with secondary caries and new caries. The patient said she was discouraged by her dental condition and knew she was about to lose some of her teeth.

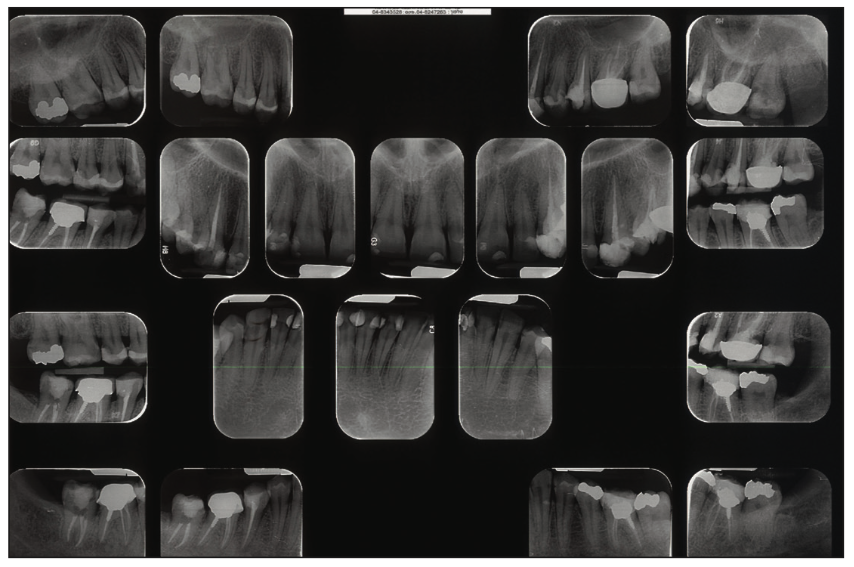

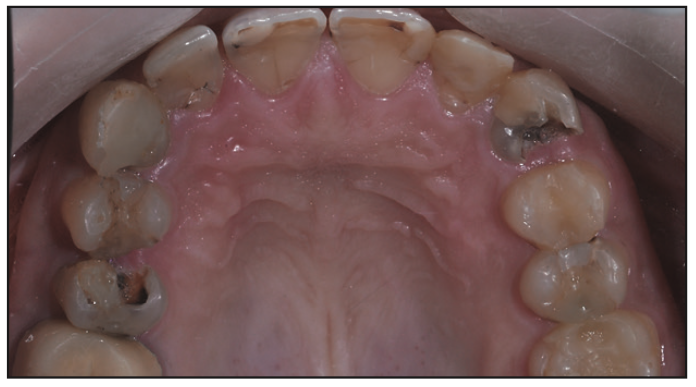

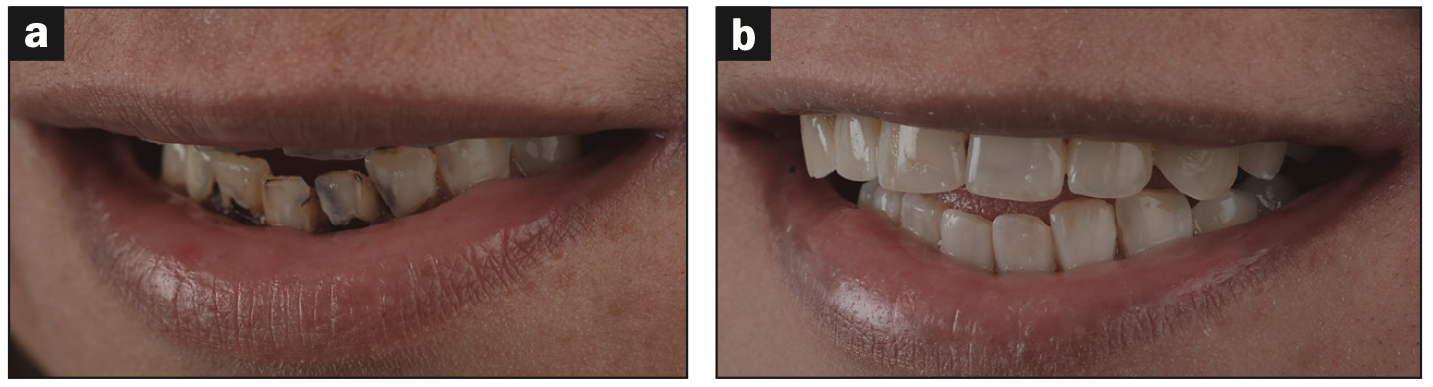

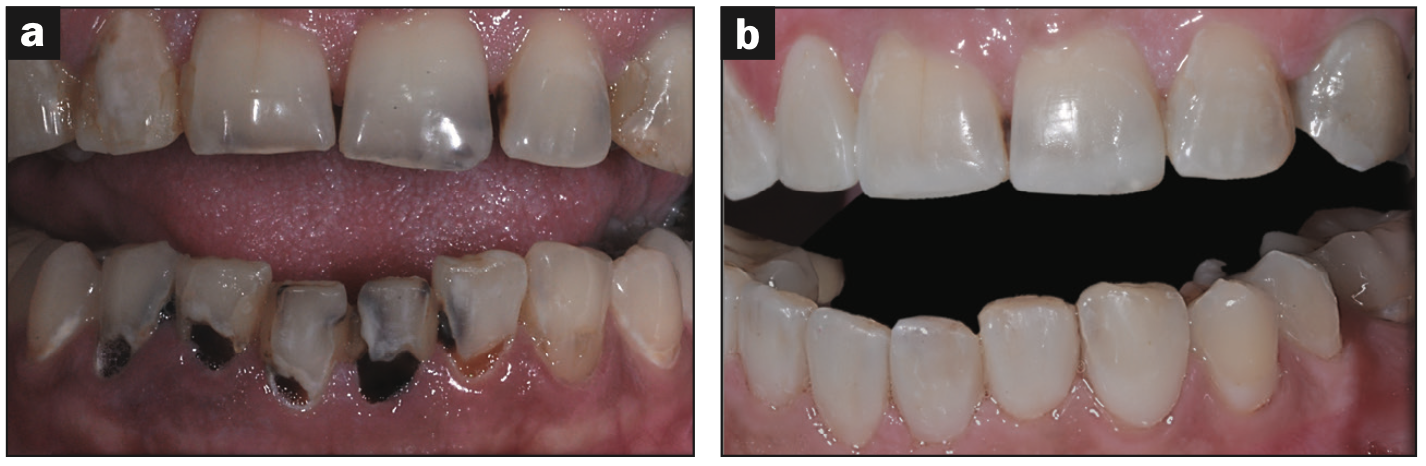

The clinical examination indicated caries at an abnormally active level: In most of the teeth, several surfaces with caries were detected. All of the previous composite restorations were found to be deficient. Several teeth were treated endodontically, and a number of teeth were restored with crowns (Figure 1). The patient’s appearance was compromised (Figure 2). Her oral hygiene was extremely poor, and the teeth were covered with a substantial quantity of plaque and tartar (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 1. Initial dental x-ray. Note secondary caries in the composite restorations that were carried out in recent years.

Figure 2. The patient’s smile prior to treatment.

Figure 3. Maxilla occlusal view. Note the extensive composite restorations and the enormous secondary caries. Choosing a conventional composite for the new restorations was not the appropriate treatment plan for the patient at such an abnormal level of caries activity.

Figure 4. Mandibular incisors at the starting point, before root planing and scaling. Note the extensive caries lesions that surround the teeth.

Not surprisingly, the patient was categorized within the high-risk group of the CMBRA (caries management by risk assessment) scale.3 The initial preparation included root planing and scaling, guidance in oral hygiene, fluoridation, and the use of toothpaste containing a high concentration of calcium and phosphate (GC Tooth Mousse [GC America]).

The therapeutic approach chosen to treat this patient was the minimally invasive approach. The principles of this minimal-intervention approach include:

- Strict preservation of healthy tooth material

- Avoidance of the unnecessary removal of tooth material

- Maintaining the vitality of the patient’s teeth

- Supragingival restorations that allow optimal maintenance of oral hygiene

- A choice of restoration materials with antibacterial properties

To adapt this therapeutic approach to the patient with rampant caries, we were presented with several dilemmas:

1. We were aware that the chance of secondary tooth decay in teeth restored with composite restorations is significantly higher than the chance of secondary caries for teeth restored with amalgam restorations.4

2. In the patient’s mouth, many primary and secondary cervical caries and many proximal caries located in the subgingival regions were detected. The literature indicates that in composite restorations, secondary caries is more common in the gingival part of the restorations.5 In particular, due to significant degradation of the hybrid layer, a degradation of about 60% of the dentine-resin layer2 was observed in some of the bonding materials about a year after the installation of the restoration. This phenomenon was observed mainly in restorations localized in the dentin.

3. Composite restorations are a convenient environment for bacteria, which can grow on the restoration surface, and composites are not restoration materials with antibacterial properties.4

4. A number of teeth were treated endodontically prior to the patient’s arrival at the clinic, but a number of other teeth were found to be non-vital and had to be treated endodontically as well. The treatment plan was to restore the teeth with the endodontic treatments in the posterior dentition using a conservative technique and to avoid preparing the teeth for crowns.

For these reasons, using conventional composite to treat cases of rampant caries is problematic and has great potential for failure. Therefore, for all the restorations performed on the patient, we used new bonding materials and this new composite material called Infinix, a product of Nobio. The composite and the bonding materials received FDA clearance in 2020 and are thus considered the first dental composite that reduces demineralization, which is part of the caries-formation process.

The antibacterial properties of the composite and bonding materials are based on a technology called QASi, in which quaternary ammonium is covalently bound to a silica filler. This material has been demonstrated in microbial studies to be antibacterial. The process starts when the QASi particles electrostatically attract cariogenic pathogens. When the bacteria come into contact with the composite, it electrostatically kills those microbes by shredding the bacteria’s outer membrane. In this way, QASi technology fights the bacteria that cause demineralization and subsequent recurrent caries.6

QASi is incorporated into both the universal composite and a dentin bonding agent. The QASi particles are insoluble and non-leaching, so nothing harmful or toxic interferes with normal flora in the oral cavity. This antimicrobial activity is designed to last for the lifetime of the restoration.

The patient’s vital teeth were treated over several sessions, each lasting several hours due to the extensive caries lesions and the subgingival location of the margins in some of the lesions. After the caries in all the teeth were removed, no pulp exposures were observed.

We chose to use a 2-step bonding material. This sixth-generation material is the gold standard of self-etching bonding materials.7

The method of preparing dental tissues for ideal adhesion is detailed below.

1. Selective enamel etching: Enamel is a tissue that contains 97% hydroxyapatite and does not contain organic matter (collagen). In order to perform effective etching, it is necessary to use 37% phosphoric acid, a strong acid that allows effective etching of tissue with a high percentage of mineral material.

Enamel etching requires a 30-second etching process, accompanied by rinsing, drying, and examination. A chalky appearance of the enamel indicates the creation of micro-retention in the enamel prisms (Figure 4). Etching of the dentin with phosphoric acid should be avoided.

2. Dentin etching: Dentin is a vital tissue containing about 70% hydroxyapatite and approximately 30% collagen fibers. In the process of preparing the tooth, the smear layer is formed, and a layer of several dozen microns contain residues of apatite, proteins that have been demineralized. This layer covers the cavity’s entire inner area, including the enamel and dentin.

Etching the enamel with 37% phosphoric acid causes complete removal of the smear layer. Its purpose is to modify the smear layer without completely removing it to avoid removing the peri-tubular apatite and allow bonding to the collagen fibers. This approach enables chemical bonding to hydroxyapatite when the adhesion is performed properly. Etching the enamel with strong acid and etching the dentin with weak acid will result in better resistance in the hybrid layer and less degradation in the months following the restoration.

The acidic monomer in the Infinix primer is MDP at a concentration of 5% and a pH of 2.8. The primer contains ethanol and 5% water, a more forgiving bonding material when working in an environment that is not completely dry. The acidic primer is applied to the enamel and dentin surface and rubbed with a microbrush for 20 seconds, then dried with a mild air stream for 5 seconds.

After placing the primer, the bonding material is placed. The bonding material has a neutral pH and hydrophobic properties, which are ideal for bonding to composite, as opposed to single-component self-etching bonding, in which these materials are acidic and hydrophilic. The bonding materials are applied to the preparation walls using a new microbrush. After this application, a stream of air is employed to disperse and refine the layer; it is then polymerized for 20 seconds.

In all bonding materials, micro gaps are created during polymerization. These micro gaps cause postoperative sensitivity, allow bacteria to populate the gaps, and cause secondary caries. The Infinix bonding material is the only bonding material available that contains an antibacterial filler. It contains 1.5% of QASi bonded to the silica-filler molecule, which creates a first line of defense between the bonding material and the deep portion of the preparation closest to the pulp.

The presence of QASi in the most critical area for the survival of the restoration creates a defensive layer that is not possible in other materials, constituting a game changer in its ability to protect micro gaps and reduce the formation of secondary caries.

The Infinix universal composite’s 1.5% QASi also provides long-term protection to the outer surface of the restoration. This results in less plaque accumulation on the teeth restored with Infinix, as well as less soft-tissue irritation and thus less gingivitis in close proximity to the Infinix-restored teeth than when other products are used.

The composite contains 80% filler, a high percentage that results in:

1. Good handling properties, good adaption to tooth structure, and good dimensional stability so that anatomy can be built prior to light curing

2. Ease when creating a contact point in Class II restorations

3. The ability to create free-hand restorations in Class IV restorations due to the good stability of the material

The universal composite is available in 2 shades (A2 and A3), although, if an additional shade of composite is needed for an optimal aesthetic result, different composites can be combined.

The author also uses the universal composite in indirect restorations of vital and non-vital teeth to elevate the preparation margins from a sub- to a supragingival finish line (Proximal Box Elevation-PBE/Deep Margin Elevation-DME). The principles of minimally invasive treatment of indirect restorations will be published in a future article.

TREATMENT PERFORMANCE

- Direct restorations were performed on multiple surfaces: teeth Nos. 4 to 12 and 21 to 28.

- Onlays and endocrowns were placed on teeth Nos. 3, 13 to 15, 19, 29, and 31.

- Amalgam restorations were not replaced on teeth Nos. 2, 20, and 18.

- Crown No. 30 wasn’t replaced (Figures 5 to 9).

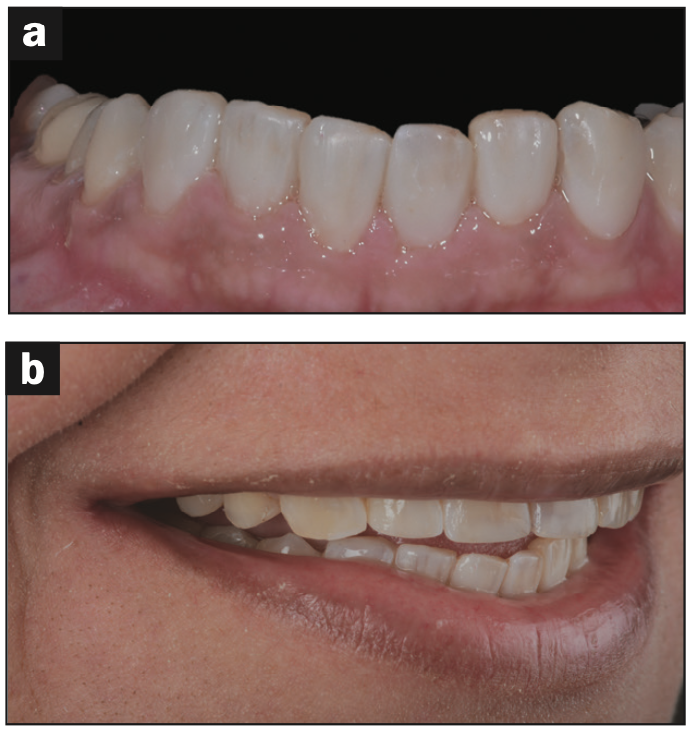

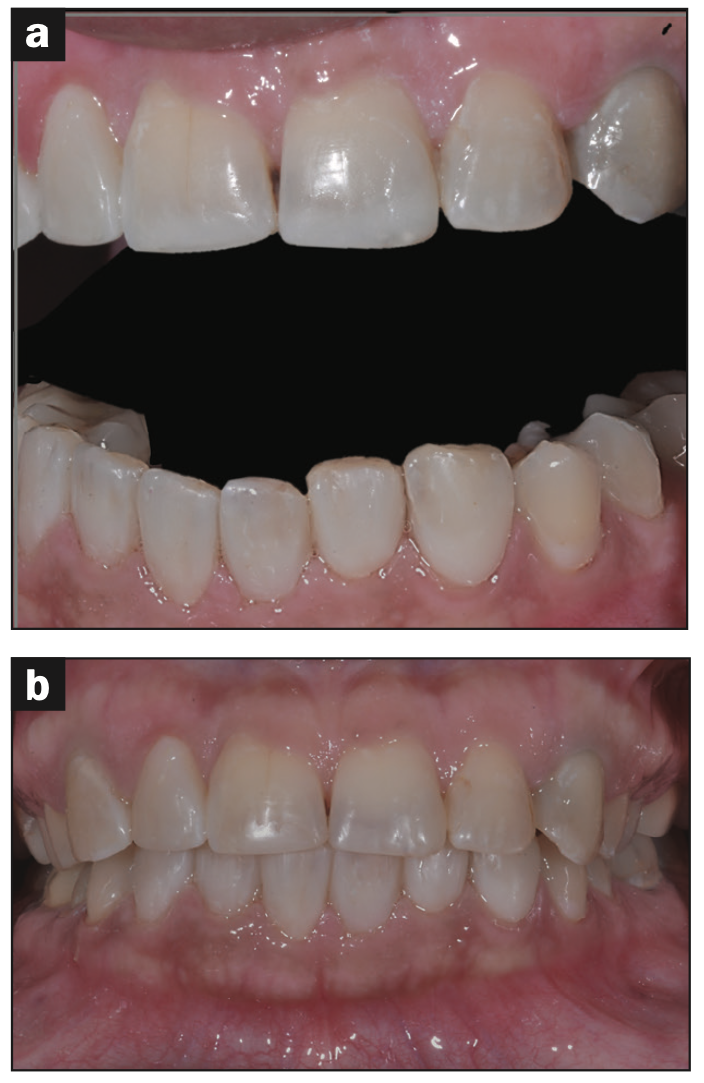

Figure 5. Frontal view of the patient before and after treatment.

Figure 6. All restorations were performed with Infinix antibacterial bonding material and universal composite. The vitality of the teeth was preserved in all the teeth. (a) Before treatment. (b) After treatment.

Figure 7. The patient’s new smile, normal view.

Figure 8. The patient’s new smile, retracted view.

Figure 9. Post-treatment maxilla occlusal view. Note the extensive Infinix direct composite restorations (teeth Nos. 4 to 12) and the indirect minimally invasive restorations (Nos. 3 and 13 to 15).

The patient became pregnant about 13 months from the date of the treatment. This pregnancy presented a challenge for the restorations because it caused multiple vomiting episodes and difficulty for the patient in strictly maintaining oral hygiene. The patient continued to visit and receive treatments from a dental hygienist throughout the pregnancy. The direct and indirect restorations were examined and found to be clinically sound restorations. No secondary or new caries were detected, and the teeth remained vital.

CONCLUSION

Minimally invasive conservative treatment of patients with a high level of caries activity is a challenge for the clinician. It is necessary to use advanced tools to monitor the causes of the disease, change the patient’s dietary and oral hygiene habits, and recommend the use of oral disinfectant products with antibacterial contents and toothpaste rich in calcium and phosphate.

The dentist should preserve maximum tooth material. The preparation margins, if possible, should be placed in enamel to allow stable adhesion rather than degradation in dentin adhesion. The finish lines of the restorations should be supragingival to allow easy and efficient maintenance for the patient.

The use of antibacterial bonding materials containing QASi makes it possible to protect the hybrid layer against the penetration of microorganisms to the hybrid layer’s micro gaps and prevent secondary caries. QASi-infused antibacterial restoration materials are the first line of defense and prevent the growth of bacteria on the surface of the composites. Therefore, the combination of antimicrobial bonding material and the antimicrobial universal composite of Infinix is recommended as the material of choice for anterior and posterior restorations. These materials are particularly recommended for use in cases of rampant caries, in patients with maintenance difficulties, and in children and the elderly population.

REFERENCES

1. Edelhoff D, Sorensen JA. Tooth structure removal associated with various preparation designs for anterior teeth. J Prosthet Dent. May;87(5):503-9.

2. Reis A, Carrilho M, Breschi L, et al. Overview of clinical alternatives to minimize the degradation of the resin-dentin bonds. Oper Dent. 2013 Jul-Aug;38(4):E1-E25. doi: 10.2341/12-258-LIT. Epub 2013 Mar 25.

3. Rechmann P, Kinsel R, Featherstone JDB. Integrating caries management by risk assessment (CAMBRA) and prevention strategies into the contemporary dental practice. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2018 Apr;39(4):226-233; quiz 234

4. Nedeljkovic I, Teughels W, De Munck J, et al. Is secondary caries with composites a material-based problem? Dent Mater. 2015 Nov;31(11):e247-77. doi: 10.1016/j.de

ntal.2015.09.001. Epub 2015 Sep 26.PMID: 2641015

5. Mjör IA, dQvist V. Marginal failures of amalgam and composite restorations. J Dent. 1997 Jan;25(1): 25-30.

6. Atar-Froyman L, Sharon A, Weiss EI, et al. Anti-biofilm properties of wound dressing incorporating nonrelease polycationic antimicrobials. Biomaterials. 2015 Apr;46:141-8.

7. Breschi L, Mazzoni A, Ruggeri A, et al. Dental adhesion review: aging and stability of the bonded interface. Dent Mater. Jan;24(1):90-101. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2007.02.009

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Wind is a graduate of the Goldschleger School of Dental Medicine at Tel Aviv University. He is a member of the Department of Oral Rehabilitation, The Maurice and Gabriela Goldschleger School of Dental Medicine Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University and former director of Advanced Aesthetics Program, R. Goldstein Center for Esthetic Dentistry and Clinical Research at the Hebrew University School of Dental Medicine at the Hadassa Ein Karem Medical Center, Jerusalem, Israel. He is a well-known lecturer in the field of aesthetic dentistry, minimal intervention dentistry, prosthodontics, adhesive dentistry, and composite materials. He is a consultant to several companies in the field of composite materials, aesthetic dentistry and prosthodontics. Dr. Wind’s clinic specializes in prosthodontics and esthetic dentistry. He can be reached at yuval@wind-clinic.com.

Disclosure: Dr. Wind reports no disclosures.