The overall economy may be getting better, but paychecks in the dental profession aren’t seeing significant growth. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), dentists saw a median pay of $158,120 (or $76.02 per hour) in 2017. That’s a slight drop from 2016’s median of $159,770 and $76.81 an hour.

The lowest 10% of dentists earned less than $70,000, and the highest 10% earned more than $208,000. That’s comparable to the less than $67,660 the lowest 10% and the more than $208,000 the highest 10% made in 2016. And among specialists, oral and maxillofacial surgeons and orthodontists had a median pay of $208,000, which is the same as their 2016 median.

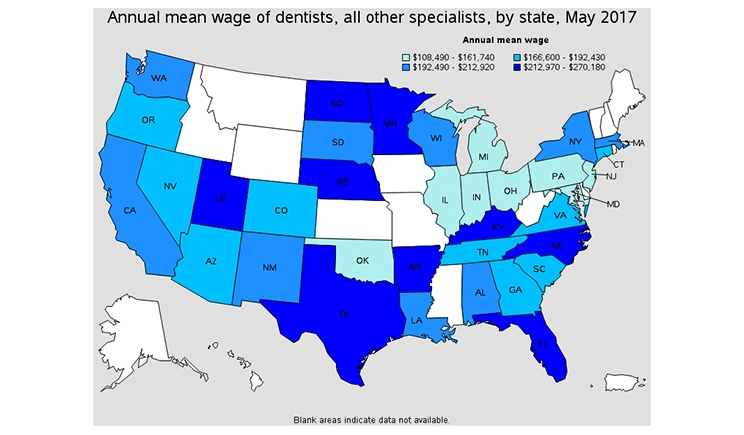

Where you practice will affect your salary too. Dentists in North Dakota had the highest annual mean wage in 2017 at $270,180, followed by Utah at $257,800, Nebraska at $252,300, Minnesota at $243,860, and Texas at $243,690. Arkansas, Kentucky, Florida, and North Carolina also fell into the $212,970 to $270,180 bracket.

While income might not be growing, professional opportunities are getting better. With 153,500 dentists employed in 2016, the BLS expects overall employment for dentists to grow by 29,300 or 19% through 2026, which is faster than the average for all occupations.

The BLS attributes this growth to increased demand for dental services as the population ages. Baby boomers will keep more of their teeth as they age than previous generations, and this trend will only grow for subsequent demographics such as Gen X and millennials. There also will be greater demand for complicated work, including implants and bridges.

Plus, with the rise in oral cancer rates, there will be greater need for cosmetic and functional dental reconstruction. And, the BLS says, demand for dental services will grow as more studies link oral and overall health. Dentists will need to provide care and instruction aimed at promoting good oral hygiene, rather than just drilling and filling.

Dental hygienists may have it better than dentists. Their median pay was $74,070 or $35.61 per hour in 2017—an increase over 2016’s $72,910 and $35.05 per hour. With 207,900 hygienists in 2016, their numbers will grow by 40,900 or 20% through 2026. Like dentists, this demand will be driven by an aging population and greater links between oral and systemic health.

Dental assistants had a median pay of $37,630 or $18.09 per hour in 2017, which is greater than their $36,940 and $17.76 per hour totals in 2016. The BLS expects 19% growth in their numbers through 2026, increasing from their 332,000 total in 2016 by an additional 64,600. These openings will be due to the same factors driving the increases in dentists and dental hygienists.

However, schedules matter. Most dentists work full time, with some working evenings and weekends to meet their patients’ needs. The number of hours worked varies greatly among dentists. About half of dental hygienists work part time, and some work for more than one dentists. Nearly one in three dental assistants worked part time in 2016.

Laboratory technicians had a median pay of $38,670 in 2017, up from 2016’s $37,680 median. The BLS anticipates 5,500 new positions for 14% growth through 2026. While demand for cosmetic prosthetics such as veneers and crowns will likely increase, though, there will be a decrease in the demand for full and partial dentures as more people keep their teeth.

Reactions from the Field

Overall, dentistry accounted for five of the top 20 highest paying occupations, according to the BLS, with orthodontists in third place, oral and maxillofacial surgeons in fourth, dentists (all other specialists) in tenth, prosthodontists in eleventh, and general dentists in fifteenth. Yet many dentists remain dubious about the profession’s potential for growth, especially as insurance continues to play a role in practice revenues.

“I expect insurance fee schedules to remain flat or be reduced, so insurance companies can increase their profits and have competitive instruments to sell to employers. Naturally, this is done on the backs of providers (dentists) and will certainly negatively impact quality of care. The myth of the free lunch is just that—a myth,” said Michael W. Davis, DDS, who practices in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Davis also notes the increasing pressure on corporate healthcare, including dentistry, to increase or at least maintain earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. Leveraged debt of these operations is additionally burdensome, he said, as interest rates tick increasingly upward.

“Since insurance fee schedules are static or in decline, profits are too often generated by upselling patients needless treatment, as well as utilization of dubious quality laboratories and questionable dental supplies. Numbers of practices also skirt state and federal labor laws to increase profit margins,” Davis said.

“Numbers of corporate clinics hoodwink customers by sales of discount dental plans, so no audit of dubious treatment plans is possible. This is the troubling truth behind corporate dentistry’s cost saving’s economy of scale,” he said.

Some practitioners believe that the BLS’s reported median didn’t seem particularly high. Emily Letran, DDS, MS, who works with other dentists in professional development, believes practice owners can easily influence these figures since they are independent providers compared to other physicians whose salaries are dictated by hospitals and other entities.

“We can significantly shift our income level by using several marketing and practice management strategies, changing not just the type of services provided but also the quality of services. By quality, I mean to provide comprehensive treatment, not just the typical restorative services, and be able to give our patients better quality of life as well as growing our income,” said Letran.

“In practice management, the practice owner can invest in technology and systems to streamline business and increase work output. Automated systems such as Dental Intel for tracking metrics, Solution Reach for patient communication, and Envisionstars for attaining Google reviews help practices achieve their goals without increasing the overhead cost of staffs dedicated to these tasks,” Letran said.

“In clinical practice, practice owners can incorporate more elective procedures, such as minimally invasive implant systems and sleep apnea treatment, or bring specialists into their own offices and create a synergistic team effort to provide more treatment at the same convenient location,” Letran added. “I believe it is a choice the practice owner makes to generate his or her own income, regardless of other economic influences.”

Other dentists have a more positive outlook for the future—particularly for those young practitioners now embarking on their careers as shifting demographics and improved oral care means more older patients who are keeping more of their teeth. But these students will need to be trained in the groundbreaking technologies that will emerge in the years ahead, too.

“With the aging population, we know that there is a projected shortage for dentists nationwide, and Touro College of Dental Medicine was established in part to help solve this problem,” said Edward Farkas, DDS, vice dean of the school.

“As the newest dental school in the nation, we’ve made significant investments in dental education, including advanced digital technologies to ensure our students bring these cutting-edge techniques to the field when they begin practicing,” said Farkas.

“With a student base from across the nation, we hope to contribute to a growing workforce of qualified dental professionals by returning our students to their diverse communities equipped with the most advanced dental training,” Farkas said.

Related Articles

What Dentists Earn: 2017 Edition

Retirement Reality: Going Beyond “What’s Your Number?”

US News & World Report Names Dentistry the Best Healthcare Profession